Laurie Kelley

March 4, 2011

When is the number 13 lucky?

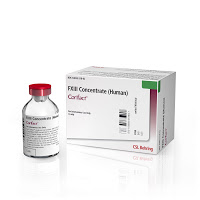

We now have a factor concentrate for people with factor XIII deficiency. CSL Behring, makers of Helixate FS, Monoclate P and Mononine, was granted FDA approval for their factor XIII concentrate Corifact, indicated to treat congenital factor XIII deficiency. This is the first and only U.S. approved treatment for factor XIII-deficiency and the fourth new product that CSL Behring has brought to the U.S. market in the past two years. Corifact is already available for use in 12 countries throughout the world under the trade name Fibrogammin- P.

Factor XIII deficiency, also known as fibrin-stabilizing factor deficiency, is rare, affecting one in two million, with an incidence in the U.S. of approximately 150 people.

Symptoms include bleeding from the umbilical cord after birth, poor wound healing, miscarriages, subcutaneous bleeding, and excessive bleeding in joints and muscles following trauma. Patients lacking the FXIII protein are also at high-risk for intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), bleeding inside the skull that can be life threatening. Studies have shown that between 25- 60% of factor XIII deficient patients will experience an ICH at least once during their lifetime.

This is great news for those with factor XIII deficiency. For more information, please see www.corifact.com and contact your HTC staff.

Great Book I Just Read

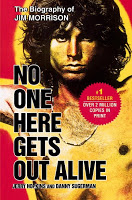

Riders on the Storm by John Densmore

“There’s the Beatles, the Stones, and the Doors,” says Paul Rothschild, producer of one of the greatest bands of the sixties. Drummer John Densmore was only 21 when he joined with three other California students to form a band that would soon skyrocket to the top at a time when the US was a nation at war in Vietnam, and with itself. With quiet Robby Krieger on guitar, methodical and rational Ray Manzarek on keyboard and Adonis-look-a-like singer Jim Morrison, the band was like no other. With no bass player, they combined blues, jazz and psychedelic rock, with some Indian strings and often very dark lyrics, about death, murder and rage. And no wonder: Not long after forming, Densmore writes about their iconic lead singer, “I’m in a band with a psychotic.”

The book is captivating. It starts in Paris, 1975, with Densmore visiting Morrison’s grave, four years after his death at age 27 on July 3, 1971 from an overdose. Returning to the hotel, he pours his feelings out in a “letter” to Morrison on the hotel stationery, which then gets interspersed throughout the book with his recollections. His memoir details his time in the band, returning now and then to the ongoing letter, and towards the end, “updates” Morrison on events of the 1980s and 1990s. Interspersed are appropriate lyrics from their songs, so that the book itself becomes quite artsy. The book gives excellent insight into what the 60s were like, what it’s like being in a band on the rise and what it was like to survive the onslaught of Jim Morrison. What’s missing, though, is what “The Lizard King” was really like. We get snapshots, snippets, and stories, but it’s as if Densmore viewed Morrison at arm’s length, even though he intensely shared six years with him. He was in awe of Morrison—who wasn’t?—and scared of him, and rightly so. Though he feels guilty at not being able to help Morrison, we have to remember he was only a young man from a humble Catholic background, ill equipped to cope with sudden stardom, wealth and the phenomenally complex, creative and self-destructive Morrison.

As if to highlight the detachment Densmore had with Morrison, Densmore dedicates the book to John Lennon of the Beatles, one of Densmore’s heroes, and also mentions Lennon’s assassination in his “letter” to Morrison, yet doesn’t mention or maybe doesn’t even know that Lennon was assassinated on Morrison’s birthday, a fact he should know as Morrison and Densmore were born only a week apart.

“We sensed rage and a possible explosion too near the surface to mess with in dealing with you,” Densmore writes in his letter to the now dead Morrison. “It seemed to have a lid on it—Pandora’s box with all the demons that wanted to be released. We never opened the box… we had to deal with your demons seeping out the side.” They seeped out and poisoned everything; the Doors had to cancel a 20-city tour when Morrison was arrested in Miami for indecent exposure at a concert (he was just pardoned this past December!). The charisma, lyrics and stunning voice of Morrison helped make the Doors a success; his addiction, rage and irresponsibility destroyed them. The book was published in 1990 and Densmore writes, “Well, we’re going on 20 years and there’s no end in sight” of the fascination people have with the Doors. On July 3, it will be 40 years since Morrison’s death, and the Doors are almost as popular as ever. I picked this book up and finished it 5 hours later—it’s compelling, honest, shocking and eye opening. A great book about one of my favorite bands and my favorite singer—for no one could sing like Jim Morrison. Three stars.

Published in 1968, this has become a timeless classic not just for sales, but for business, for life. A very simple story, set in the time of the birth of Christianity, with profound principles about being your best, making your life, not being a victim to chance but defining who you are, what you are and what you are to become. You can finish this in one sitting, but guaranteed it will stay withyou a long time. You can read this as a business self-help book, or as a way to build better character and life. I read it a long time ago for one and now read it for the other. Much in the style of Paolo Coelo, though Og came first! Five/five stars.

Published in 1968, this has become a timeless classic not just for sales, but for business, for life. A very simple story, set in the time of the birth of Christianity, with profound principles about being your best, making your life, not being a victim to chance but defining who you are, what you are and what you are to become. You can finish this in one sitting, but guaranteed it will stay withyou a long time. You can read this as a business self-help book, or as a way to build better character and life. I read it a long time ago for one and now read it for the other. Much in the style of Paolo Coelo, though Og came first! Five/five stars.