Joy in the Morning

I flew into Tanzania today, a quick one-hour flight from Nairobi. I was greeted so warmly, so kindly by the members of the Tanzania Hemophilia Society, who made me feel instantly welcome and part of the family. Richard Minja, founder, and I have been communicating for four years, working to establish the society, and when we met he greeted me with an unabashed hug! We feel as though we have already met; so strong are the ties that bind people who live with bleeding disorders.

But first, let me finish telling my tale of Kenya. I wish I could bring you all with me to experience what I experienced: glimmers of hope in patients who were desperate for care, for a solution to some very difficult problem. Overall, Kenya has a great physician and hospital at Kenyatta Hospital, but the problems faced by Kenyans with hemophilia are institutional, cultural and logistical. Overcrowded emergency rooms mean that patients wait hours before being seen: those with serious bleeds risk life itself. Factor often is not available, and what little there might be must be used sparingly. The medical staff devote their entire lives to helping patients but even they cannot overcome a culture in which patients are meek, do not speak up when they are bleeding, and do not challenge the current system. The traffic in Nairobi pretty much dictates everything; your entire day is planned around how best to avoid traffic. You can literally sit for hours, inching along. Patients can never get to a hospital quickly this way. So many patients live very far from the hospital, and many do not own cars. How can they get from a rural house on a long, miles long red muddy road to a highway and then into Nairobi when they have no car and no reliable public transport?

So we know what we must do.

On Thursday, I flew back from Zanzibar, and pretty much just sorted myself out the rest of the day, trying to keep up with email. Maureen and her partner Sitawa picked me up at the airport and we met with Salome and Dolphin, two members of the board of directors, to finish plans for the big charity event they were holding Friday.

On Friday, April 24, we started our day early by visiting Mrs. Eva Muchemi, of the Diabetes Management and Information Center. She was wonderful! Diabetes and hemophilia actually have a lot of things in common, as both are chronic disorders. Eva gave us many tips in running a nonprofit and establishing family-based programs for education. One of the coolest things I learned (no pun intended) was how to create a “traditional cooler,” to store insulin or any biological product. Using two tin cans, charcoal (abundant in the developing world), and a rubber ball as a stopper, local artisans can make these insulated cooler cheaply. In that way, patients can store insulin at home!

Next stop, the hotel where the event would take place, to check on preparations. The rich smell of roses filled the air and I can see that Maureen and team pulled out all the stops for this event, which is in memory of Jose, Maureen’s firstborn, who died just shy of his sixth birthday on April 25, 2007. Rather than submerge herself in extended grief, she empowered herself to create this society to ensure that no other child should die of untreated bleeding.

Then, Salome, who is a nurse at Kenyatta and also a mother of a child with hemophilia, and I went to visit Charity, a vivacious mother of three who lives in Lumuru, on the outskirts of Nairobi. As we finally disentangled ourselves from vicious traffic, and patiently endured a police roadside checkpoint, we zoomed along the highway. Immediately the countryside unfolded, and a beautiful Kenya revealed itself. It’s a double-edged sword: along with the lush countryside comes increased poverty, though I have to say that rural poverty is quite different than urban poverty. What you forfeit in modern conveniences, you make up for with clean air, space, and peace. But life is hard there.

I snapped dozens of photos long the way, which will have to wait till I am back in the US, where we have high speed Internet. It takes too long to upload photos. But what photos! Wait till you see them all.

Turning onto a rusty and rock-encrusted dirt road, we bounced and banged our way to Charity’s house. We passed donkey-pulled carts, women balancing immense loads of vegetables or firewood on their heads, and random donkeys grazing on the thick grass. Finally we arrived.

Charity is a woman with a dazzling smile and lovely, British-clipped accent. She was so excited to have an American visiting her home-what an honor for her! But it was an honor for me. How often do we get this chance, to share intimately in the life of a struggling soul? Out of the house shyly emerged her children: Patrick, 14, Daniel, 11 (who has severe factor VIII deficiency) and giggling Ann, 5. Another cousin tagged along. Daniel actually looked in good shape, though a bit small for his age, while Patrick is slim and robust, strong. We had a tour of the home, the separate “kitchen,” which is a wooden shed, inside which was a steaming pot of soup. The smoke was really thick inside: directly above the pot was a cord of wood, which was being dried by the smoke. Nearby were vats of water–their household supply. Back out in the bright sun, we went to the rear of the house, where I was surprised to see two cows, which give fresh milk daily, and a cute calf. A small cat followed us about. The kids started to loosen up and we took photos.

Inside, we listened to Charity’s story: Daniel misses a lot of school though he is a good student. Education is absolutely paramount to them, for it ensures a future for the entire family. There’s no such thing as welfare for the elderly. You are cared for by your family or not at all. So you’d better believe these kids get educated. Daniel’s knees show signs of arthropathy, especially in the left knee. Unbelievably, though they have electricity, there is no TV, no washing machine and no refrigerator! Try to imagine no refrigerator, especially for a child with hemophilia. A small one costs $200 and we pledged to source finds for one. The kids smiled broadly when I whispered this might mean keeping the occasional Coca-Cola in the house for special occasions.

Patrick wanted to see photos of my family, and my pets, and when I handed him my iPhone, he wasn’t phased by the technology. He immediately got the hang of its touch, and skimmed through my photos, asking such intelligent questions.

David, the father, came by, limping. He had been mugged two years ago, and left with a shattered leg and has been unable to work. When I broached the subject of their income, I think tears came to his eyes. For a man not to be able to support his family seemed wrong. I looked about the humble abode, seeing how clean and neat the children were, the wonderful food Charity placed on the table for us to eat, and how attentive they were. Charity earns $35 US a month selling vegetables from their small farm out back.

We will enroll them in Save One Life, which will almost double their monthly income. Charity said they need money most for transport to the city for treatment. They almost always will need a taxi or to pay a driver.

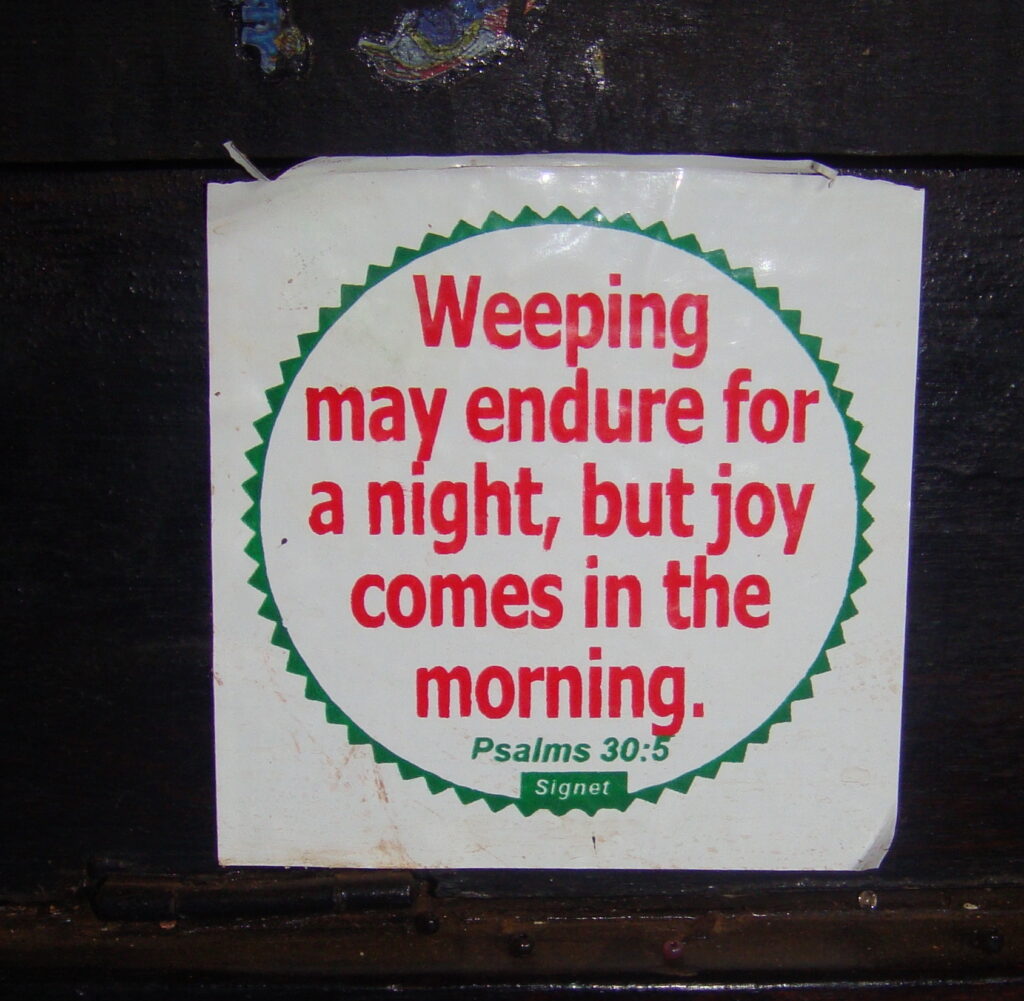

As we spoke, I glanced up at the cupboard next to me, on which was an appropriate plaque at eye-level: “Weeping endures through the night, but joy comes in the morning.” Psalm 30:5. So appropriate for a child with savage joint bleeds, and a mother who holds him all night helplessly. To see their smiles today meant we have brought some measure of joy.

When it was time to leave, there were hugs and the kids were all smiles. In fact they piled into the back seat of the car for a lift to homes near the highway, so they could visit a friend. And we returned to the congested city for our big charity event, which I will need to write about in a day or two. Stay tuned!