Island of Dreams

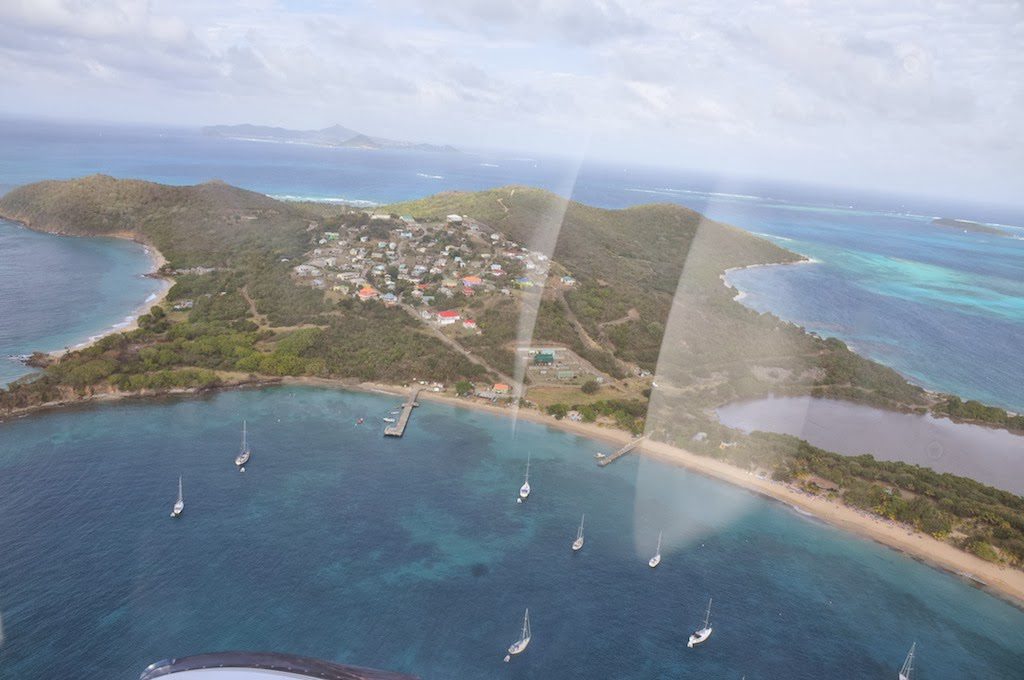

I had forgotten just how beautiful are the waters of the Caribbean. Flying overhead, from Bridgetown (Barbados) to Union Island (St. Vincent and the Grenadines), even the prolific and troublesome brown sargassum, which spread like a brown sea-snake for miles and miles in the turquoise-jeweled sea, could not stop my awe of this place of paradise.

This was my third trip in 22 years to the island of Mayreau, to visit Kishroy Forde, a young man with hemophilia. I first visited in 2001, when Kishroy was only 6, at the bequest of his mother. She had called me collect, after a tourist gave her a copy of my book, Raising a Child with Hemophilia. The tourist was a nurse, and Kishroy’s mom had told her she had two children with hemophilia. My number was in the book, and Kishroy’s mom called and begged—no, demanded— that I come and teach her how to infuse her son. At once I loved her attitude and agreed.

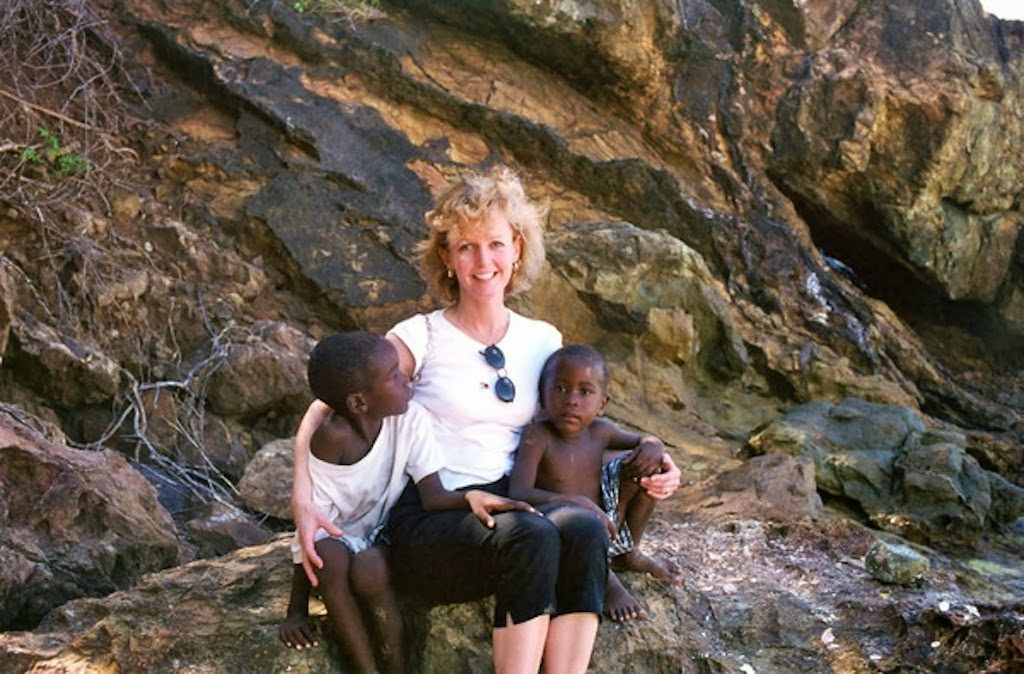

I convinced a nurse from Miami to accompany me, and together we took several flights and then a very low-in-the-water wooden outboard boat to the remote island of Mayreau. At that time it had no electricity, government, or medical care. My nurse friend taught Kishroy’s mother in one afternoon how to prepare and infuse factor while I took the children—Kishroy, his four-year-old brother Kishren and their two half-sisters—to the beach to keep them busy. When we returned, Kishroy received his first ever infusion of factor, which I had brough with me. I shipped them from time to time with factor.

A lot happened in the intervening years. Despite our donations of factor, little Kishren died of a GI bleed. Because on Mayreau, nothing happens fast. To get to a hospital, you have to find someone with a boat willing to take you there. And it’s a 30-minute, bumpy ride over choppy waves. The main hospital staff did not know much about hemophilia in those days. After his death, the mother left the family and moved to another island, leaving behind Kishroy, 11, now without his brother or mother. And last year, his best friend, and cousin, Tevin died, age 25, of a brain bleed in his sleep. This one hurt Kishroy the most.

Luckily, Kishroy has an exceptional father, Adolphus, who was a fisherman at the time. And an island full of relatives. I returned in 2014, to see the little boy I knew had grown to a young man now 6’3” tall! I stayed only for a couple of days, enough to give him more factor, some gifts and to see how he was. The island now had electricity, and a nurse who visited once a week.

Then, Save One Life stepped in to help. Kishroy received a sponsor: first, the Castaldo family of Illinois; then, John Parler of Florida. Both families have children with hemophilia. Kishroy also received a scholarship to attend post-high school training. He learned how to repair computers, and studied electrical engineering. This would alter his life.

I continued to donate factor when needed. Kishroy would call, text or WhatsApp me to request what he needed. I was impressed that he never asked for anything more than what he needed.

The day finally came when I could get away post-Covid and return to see him. So I spent last week with Kishroy, now 28. I arrived by boat again, and he was on the dock to greet me. This time I was amazed at his growth—not in height, but in maturity. The little boy I knew has become a man, who still lives in a tiny island of only 450 people, but who has big dreams. In fact, Mayreau now seems to be a place of big dreams.

It’s hard to overestimate how strange it is to live on such a small island your entire life. I doubt Kishroy has ever been to a movie theater. He grew up with a house with a rain vat to collect fresh water, an outhouse, and no electricity until 2007. He is surrounded by family and neighbors, and knows every inch of the island. To go anywhere requires a boat. The sunsets are spectacular, the people unhurried and kind, the vibe very cool and serene. Crime? “Sometimes someone will have too much to drink and will need to be escorted home,” Kishroy shared. There are only three policemen on the island, and one is—of course—Kishroy’s cousin Owen. I joked to Kishroy that I would just assume that everyone we met was his cousin.

How do you dream and plan, when your life is so literally limited? And you have suffered not only such losses, but have a life-threatening blood disorder and no medical facility to help?

Kishroy may be one of the most self-reliant people you could meet. He not only can fix just about anything electrical, he can repair out board motors, knows plumbing, and does construction. His computer skills got him a job as Director of Operations for a new tourist spot on the island, in a location perfect for kite-surfing, which is huge here.

In addition, he is transforming a donated two-room dwelling near the main beach into a hardware store. He came up with a brilliant idea. Seeing the multi-millionaire yachts and catamarans that arrive each week for a quick stop, knowing the fishing industry and need for properly functioning outboard motors, Kishroy noticed that every time someone needed a repair, they had to plan a trip all the way to Union Island or the St. Vincent mainland. Time-consuming and aggravating. He realized that Mayreau needed its own hardware store. He began clearing out the dwelling and installing shelves, and hopes to open this year, and turn a profit in a few months.

It would be easy for Kishroy to succumb to despair and depression over his losses and suffering, but he never complains. He turns hardship into action; difficulties into dreams; dreams into reality. He may live out his life on this small island, but he will be king of it. It’s quite a metaphor for those of us in America, who might think we have it tough. We have no idea. It takes a visit to Mayreau to put it into perspective. Dreams matter and dreams make the difference.

I left Kishroy with enough factor for about six months, thanks to all the donations we have recently received. He left me feeling incredibly proud of the man he has become, and humbled by his positive attitude and strength. I cannot wait to return—next year. Read the 2014 visit here.