“Safari” through Zimbabwe

My trip to Zimbabwe has come to a close. I am preparing to leave today, with mixed feelings. There is so much hardship here, but so much potential!

Friday was spent mostly in transit. Peter and I traveled together with his family: Laureen, his lovely wife, who shares the same name as me; Prince, his 11-year-old son; and Nkosi, his active and mischievous 3-year-old son. The trip was over 4 hours north to Victoria Falls. We traveled mostly in the evening, which is risky as there are animals in this very rural and wild land. We arrived safely and settled in.

Saturday we had quite the day! We began with a helicopter ride over Victoria Falls, the longest waterfall in the world, which creates a natural border between Zambia and Zimbabwe. Laureen and the boys had never flown before, and this was amazing! The boys were just fascinated and so excited!

Then we had a hike through Victoria Falls itself to see this stunning natural wonder of the world. Shadowing us were a troop of monkeys who were quite bold. We also saw deer along the path. The views were many and just indescribable. Vic Falls was discovered in the mid-1800s by British explorer David Livingston.The tremendous water power from the Falls kicks up spray and creates a rain forest all along the length of the Falls.It was hot that day so the “rain” felt great.

Finally we had a night safari through the Vic Falls game reserve. Safari means “journey” in Swahili, and was introduced into the English language by Richard Burton, the famed Irish explorer who charted interior Africa in the mid-1880s. On this journey, we saw elephant, rhino, hippo, impala, zebra, wart hog, water buffalo and tons of bugs. Our guide Mike was fantastic and taught us a lot about each animal, more than you would ever learn on a TV show, and the delicate eco-system that keeps all things alive in their symbiotic relationship. We didn’t feel so symbiotic, however, particularly when we stumbled upon a 100+ herd of water buffalo, who stared at us menacingly. Water buffalo are considered the most dangerous animal in Africa. And they stood only a few feet away!

As wonderful as the day was, Peter and I couldn’t help but continue to brainstorm ways to help the Zimbabwe Haemophilia Association get organized, raise awareness of hemophilia in the country, secure funds and most immediately, help the children in dire need. Top of our list? Elton, the 17-year-old with the hideously swollen knee. He needs to go to South Africa at once for testing to try to save his leg. We have a massive to-do list when we each return home.

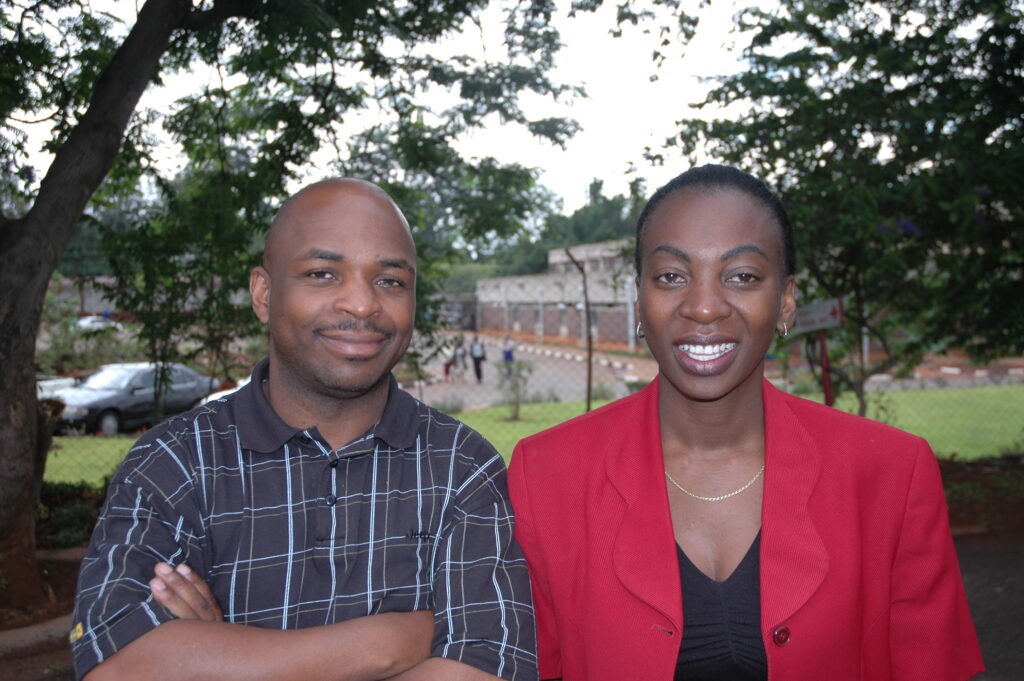

I must end my trip now. But let me thank Peter Dhalamini for his superb assistance all throughout my trip. Peter organized every aspect of it and is well respected and beloved by the hemophilia community here. He has hemophilia, has laboratory training, and is a born politician! He knows everyone and can enlist just about anyone’s help. I cannot thank him enough for making this trip so safe, effective and enjoyable. Thanks also to his family for sharing the last leg of our trip together.

Thanks also to so many others: Lenox, Dr. Mvere, the ZHA, Collin Zhuwao, Simba… and everyone who assisted. Zimbabwe is a tough place to live. Food, cash, fuel, foreign exchange, medicine and basic necessities are all hard to come by. But its people persevere with grace and dignity. Gentle and patient as they are, Zimbabweans don’t have the luxury of waiting out the ravages of hemophilia, and that is something we are about to change. Help is coming.

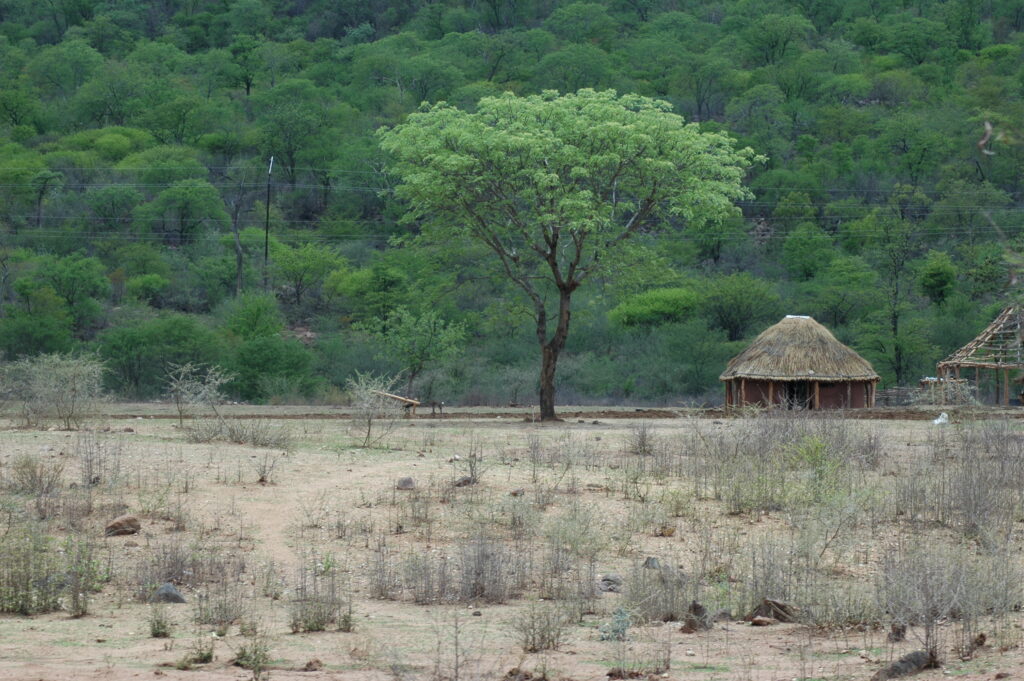

(Photos: Victoria Falls; Impala; One of Big Five; How the other half lives)