Nepal Part 3: “You’ve Been Saving Us”

Was it the

Was it thealtitude? At 4,430 feet, being in Kathmandu, Nepal is like being in Denver. It’s enough to slow you

down and dehydrate you if you are not accustomed to it. But I thought just do it. Go to see the famed “Monkey Temple.” Wednesday, September 2, was my day off.

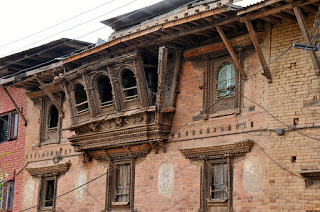

within inches of one another and somehow avoid accidents. The driver offered to

stay and wait an hour, which is all that it took. I recall being here in 1999, but with the April 25 earthquake, this World Heritage Site is in shock. The earthquake caused extensive damage to the temples and buildings. Dusty red bricks were piled up, or avalanched down stairs. Temples had huge cracks

in them, with plaster curling off them. Rhesus monkeys scooted up the sides of the

temples and into the doorways to steal the food offering left by pilgrims. Incense

mixed with acrid odors. And above it all, the eyes of Buddha stare down placidly and eternally from the highest temple.

Today I met

Today I metwith the beneficiaries of Save One Life and presented their money to them. The families were waiting for me and Laxmi, and I

smiled and waved at them when I entered, being casual so they would feel comfortable. Many

smiled back. The logistics were wonderful: a beautiful small stage,

bedecked in red; a big sign announcing Save One Life Fund Distribution. So many

young boys and older boys and families showed up.

ceremony began; there were many speeches and welcomes. I recall

Beda, man with hemophilia and president of the Nepal Hemophilia Society, said to the audience, “Pain and hemophilia are synonymous.” And then, “My mother used to

weep a lot,” as he

recounted his own childhood without factor.

speak, and they did, from their hearts.

Mrs. Chaulagain gave a speech about her two sons with hemophilia, Pranit and Pratik. There was domestic violence,

Mrs. Chaulagain gave a speech about her two sons with hemophilia, Pranit and Pratik. There was domestic violence,Laxmi translated for me. Her husband used to beat her; how

dare she provide not one but two sons with a chronic disorder for which there was

no treatment! He eventually left. They lived in poor conditions, and she

struggled to raise two boys. She thanks Save One Life and said she benefited

from the program and to keep it going a long time!

and said, Our government won’t give treatment to us! He said all

the hemophilia families are happy with Save One Life. They use the money for

school fees.

with factor VIII deficiency; she is very happy with the support from SOL. Her

husband lives in another country, trying to earn money to send to them. So this

really helps her.

young man, 18, spoke: he said it was difficult to have

hemophilia during exam time (which is much more stressful in these countries

than in the US). He thank us for Save One Life. He described his

pain, bleeding at night, and sometimes felt it was better not to have been born

than to be born with hemophilia. He lost a job due to so many bleeds. “Our

government has not recognized us,” he lamented, “because outwardly we look normal, so they

don’t pay us attention.” His speech was so impassioned about suffering. “You’ve been saving us,” he said. “It’s

because of you. I want to say more, but I cannot express it, the level of pain

I felt.”

Then Nawraj sang

Then Nawraj sanga song that he composed. It was mournful, deep. Loosely translated, he sand, “I’m living alone, crying alone. Because of you, hemophilia…the pain is too much to bear! I’m sad, crying!”

And remember, on top of all this, these families have suffered through a tremendous earthquake that destroyed many of their homes!

And remember, on top of all this, these families have suffered through a tremendous earthquake that destroyed many of their homes! speeches came questions about hemophilia, which Ujol kindly answered. Then the ceremony:

we had gift bags for all the kids, courtesy of all the give-aways from NHF just

recently. Yes, I shamelessly confiscated about 50 bags from one homecare company, squeezy

toys for the kids veins from another.

gifts. The older ones got t-shirts with hemophilia slogans on them (another involuntary

gift from yet another homecare company!). And each child received their annual

funds from Save One Life, about $240. For some this is a lot of money.

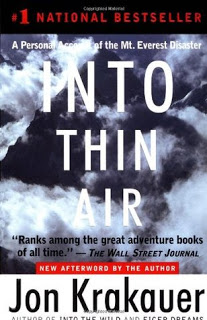

Then I gave a

Then I gave aspeech! I started by asking what the highest mountain in the world was. Of

course they knew; it’s right in their country! Sagarmatha, better known in the

West as Mt. Everest. And I shared the story of a young American man with

hemophilia (Chris Bombardier) who plans to climb that mountain. We talked about

what’s possible, even without factor, and what’s possible with factor. Dreams,

goals… and never give up. I asked many children, What’s your dream? We went around the room asking each child: Engineer,

musician, teacher… they all had dreams. I told them we want to help make their

dreams come true.

buffet of delicious local food: rice and chicken. The children played with

their new toys, and soon, the families dispersed happily. I too went back to my

hotel, happy, moved. Dedicated to these fine families.

picked me up and we drove back to the NHS office, through the blackened air. The pollution in Kathmandu is deeply unhealthy; I often felt like I was hitched to an exhaust pipe. About 33% of the population wears surgical masks outside, and eventually I did too.

a room full of wonderful, handsome young men, all ages 21-35. I was surprised

to see Deepak Neupane present; his eyes lit up when he saw me. I first met him

in 1999, when he was only 12 years old, and severely crippled. He became the

poster boy for WFH, and to this day they still use his image. He has

his hurts, is stoic, not overly friendly. But Deepak is married. It was a happy reunion and he says he

remembers me.

Raju, with a shock of dark hair, said, “Ma’am, I have to tell you this. You look like Barbie

doll!” The boys all laughed.

notes as they spoke, while Laxmi recorded their names and ages. At the end,

when they had finished, I told them my name (they all knew) and said, And I am not going to tell you my age! And the

laughed in return.

Lamsal, age 27, a government employee, is the chair. He’s an impressive young man , soft spoken, a rising leader,

mature and responsible. I met Ashrit BK, who has an inhibitor, 26 years old. He received a scholarship from us but is not attending now due to

bleeds. His left hand appears to have Volkman’s contracture.

Yankees hat on–dreams to be a computer engineer and used my analogy from my speech about having dreams.

learned that the Youth

Committee members are elected with two-year terms. They organize a blood donation

camp twice a year. They are primarily social: sharing each other’s pain and what happens to each

other. They hold a Youth Camp annually, just the guys, usually for 5 days, and

they have lectures and do social things. This year they visited the mid-Western

region and had medics come lecture.

When I asked if they did physical therapy at home, the whole room groaned and

eyes rolled. Oh, I hit a nerve. I felt like the mother asking her sons if

they made their bed or did their homework. Yeah, they know what to do but often “forget” to do it. Boys are the same the world over!

subject was marriage. In Nepal, arranged marriages are still common. What prospect

does a young man have to marry, when he is poor and disabled? Jagatlal (“Monsoon”) is married but his was a love match.

They all agreed it was difficult; the girls often leave them when they see how

hard it is for them to have hemophilia. Krishna, a handsome young man with

large, soulful eyes, told me his girlfriend left him. It hurts a mother, all

mothers, to hear this about a young man.

To break the

increasingly somber mood, I brightly suggested a “Love Program” for the Youth

Group and they burst out laughing. How the Nepalese love to laugh!

help.

shot some video of the boys telling their story of the earthquake, which was

emotional. Raju confided he was nervous (I think afraid of becoming too

emotional) and he talked on and on cathartically. His parents are

still living in a tent four months later.

they were coming back from camp when the earthquake struck. On the bus, they were

frightened; they saw people crying, and weren’t sure at first why.

group shot, me and the boys. I gave them all my business cards, told

them they were the future leaders of the Society so learn leadership! And to be

mentors for the young ones, who need them. They presented me with a beautiful wall hanging of Buddha.

Beda walked me from the hotel down to the main street so I could get a taxi. He

is disabled, and yet never complains. He rode in the taxi with me, so I would be

safe. He is a man of few words, but confided, You inspire me. I admire all your

work for all the people with hemophilia around the world.

it was one of the highest complements I had ever received.

am, after waking up off and on since 10:30 pm, but it was overall a good sleep.

I hurriedly dressed. I pride myself on being

punctual and responsible. I tiptoed to the lobby, awaking the poor guys on duty

who were flopped on the lobby couches. And waited in the lobby for my ride. One

of the young managers, tall, thin and bespeckled, asked who I was waiting for? When

I replied The Mountain Flights tour, he said the ride was coming at 5:45

am. I could have slept another whole hour!

I went back to

my room sheepishly, lay down and actually fell asleep at some point. At 5:30 am,

back in the lobby, and the ride appeared. The trip to the airport was fast, and

the wait was until 7:15. Finally they

called our flight– Buddha Air 101, and I was hurried to the crowded bus which

took us to our plane. I didn’t expect much from a quick chartered flight but

the plane was pristine. We each got a window seat. Soon

we were aloft, and as we pulled away from Kathmandu, I saw the gray, dirty air,

which left the surrounding hills only blue silhouettes, become clearer and

cleaner, and the land becoming green with rolling discernible hills, dotted

with colorful pillow-candy colored houses. We were finally aloft, 22,000 feet

and within 20 minutes the Himalaya were in view.

There are no

There are nowords to describe how you feel. Your heart leaps with awe, with love for these antediluvian

guardians of the world, formed in the violence of the birth of a planet. The

first jutted straight up above the clouds like a sentinel, far away, like a

warning to be careful of the approach of the others. They almost seemed to have

personalities. They were majestic, powerful, magnetic. Then there were more and

more. I felt like I

was gazing upon the Gates of Heaven.

A silence fell on the

A silence fell on theplane as we stared at the snow giants. Soon, mighty Everest itself. Distant,

remote. I cannot imagine what it could take to climb it and felt the urge to go to base camp some day!

came within distance it was too much to process. The sharp drops, the edges, the

crevices, the seracs. One after another and another. Oh, they are just rocks,

but what beauty! What

spells do they cast over us that suddenly make us want to be there, climb them even

though we know we would put our life at risk?

All too soon we

had to return. That evening, I boarded Qatar Airways and left Nepal for the other side of the world.

See the full Gallery of photos of Nepal:

https://lakelley.smugmug.com/InternationalTravel/Save-One-Life/Nepal-2015/51907135_ww8cL6#!i=4344863638&k=3hmP65P

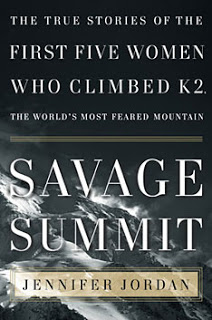

K2 remains the most dangerous mountain in the world, with a death rate of 25%. Until 1986, only men had summited the Savage Summit. In this book, Jordan chronicles the lives of five women who made mountaineering history: the ones who summited K2. Ninety women have scaled Everest; of the only six women who summited K2, three lost their lives on the way back down. I worried about this book being a glorification of women who climbed K2 (Alison Hargreaves was mother of two children under age 6 who died after summiting), as her sympathetic and rather feminist intro set the tone. But I was impressed that Jordan shifted into journalist mode and objectively examined the lives, loves, passions and mistakes of these unmistakably courageous, complex and yet sometimes myopic, women who were compelled to risk their lives… and often lost their lives in pursuit of a dream. Four/fives stars.

K2 remains the most dangerous mountain in the world, with a death rate of 25%. Until 1986, only men had summited the Savage Summit. In this book, Jordan chronicles the lives of five women who made mountaineering history: the ones who summited K2. Ninety women have scaled Everest; of the only six women who summited K2, three lost their lives on the way back down. I worried about this book being a glorification of women who climbed K2 (Alison Hargreaves was mother of two children under age 6 who died after summiting), as her sympathetic and rather feminist intro set the tone. But I was impressed that Jordan shifted into journalist mode and objectively examined the lives, loves, passions and mistakes of these unmistakably courageous, complex and yet sometimes myopic, women who were compelled to risk their lives… and often lost their lives in pursuit of a dream. Four/fives stars.