Nepal Part 2: Hope Among the Ruins

|

| Laxmi (our lovely program director of the Nepal Hemophilia |

When visiting developing countries, I love visiting hemophilia families out in their homes, something I’ve been doing for almost 20 years. These can

be rough days. It’s hot, we’re at a high altitude in Kathmandu, Nepal; my heart

pounds when I exert myself too much, and I get dehydrated quickly. But think of

what these families endure, especially post-earthquake. They give me strength.

|

| Ujol, Guyatri, Binita, Laurie, Barun, Nirmal, Manil |

items for any kids we would visit. We dodged

the traffic jams of downtown Kathmandu and hit the outskirts. Our first stop was not too far. We parked the

car, stepped out. Before starting the ascent of stairs to our first home, I noticed a lowly worm

writing in the dust at the foot of the first stair, ants crawling on it. I love

garden creatures, worms especially (I guess because they are so helpless), and

always am fascinated when I find them. To the horror of my hosts, I bent over

and picked it up and tossed it gently into the plants, so it could live. The

ants would surely eat it. Laxmi gasped… but Beda said, “It’s a living thing,

too.” “Yes, I added, and they are good for the earth.” I made them laugh when I

cheered, “Save One Life!” Or worm.

|

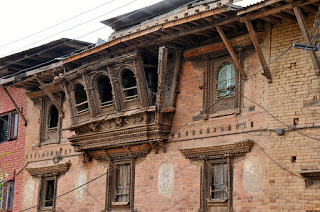

| Living in a shed |

visited was grand, tall, mounted on a small hill. But it was damaged in the earthquake

and now has been deemed unlivable. Binita greeted us; she’s a beautiful woman, but

her eyes carry such sadness in them. Her husband, a handsome man in his early

40s, died last year of cancer. This leaves her a widow, never able to remarry

according to custom, and alone now with a child with hemophilia in a land that

provides no factor, save for donations that trickle in. There are never enough

donations for the needs.

warmly and we hugged, as if we had known each other for years. We gingerly stepped

inside. Cracks and fallen plaster abounded. We climbed the wooden stairs, up to

the second and then third floors, until we stood on the upper balcony, which

provided a rich view of lush Kathmandu Valley. What a shame; this is truly a

lovely house.

a handsome young boy with a dazzling smile gladly let us take photos.

Back downstairs

Back downstairsand we navigated through the dirt and sometimes mud to Binita’s temporary

house. This means she lives in a corrugated steel shed. Yes, a shed. It bakes

them in the intense heat, and deafens them when the rains come. There is no

insulation or luxury. The carpets on the floor were soaked. We kicked off our

shoes at the door, as is the custom, before entering and our feet were wet

immediately. Kindly, Binita poured us Mountain Dew, a popular drink here. We sat and chatted. On the wall were photos of

her and her husband from when they got married. A beautiful couple, full of

hope.

about her situation. “Will she be able to remarry one day?” “Oh no,” Laxmi

said. “She cannot.” Many women, some young, lost their husbands during the

decade-long armed Maoist insurgency, I’ve read. To remarry, even when widowed

at the tender age of 21, would be to flaunt the social order. And the pressure

can be intense and cruel. It’s difficult for a woman to be single here. Almost

impossible. Binita added, “Nine people live here too.” Her in-laws, and more. I

looked around slowly. The shed couldn’t be more than 15 ft x 20 ft. Nine

people…

|

| Reconstruction everywhere |

When we emerged from the

shed, we caught Barun (a man with hemophilia who used to be on the executive

committee of the Nepal Hemophilia Society) smoking over by a barrel. We

tsk-tsked him but he jokingly quipped, “My painkiller.” We trudged back to the car a slightly

different way, and eventually down a paved road by a massive wall of stone.

“This had been totally collapsed from the earthquake,” Laxmi narrated. Looking

up, we saw men diligently at work, cementing the new stones in place. It seemed

everywhere in Kathmandu construction was happening.

more rural area, in the Kageshwaori Municipality, a town called Sanchez. The

drive was probably not more than 40 minutes. We parked near a field, and then hiked

down a dirt road. Up ahead was a terrible site: a brick home, completely collapsed.

Caved in, red dusty bricks strewn everywhere, but mostly in a vermillion heap.

Laxman, the father, stood nearby. He has a handsome, intense face, with a flash

of white teeth and readily smiles. Which is hard to believe when you look at

what is left of his house. Puskar, who was at school, is 11, factor VIII

deficient.

with questions: where was he when the quake hit on April 25? What happened?

|

| Ujol and Laurie at Puskar’s home |

was outside; no one was in the home, thankfully. Indeed, it seems that everyone

considers themselves lucky. Lucky that it was a Saturday, and more people were

not in office buildings. Lucky it was not a school day, or more children would

have died. Lucky, lucky, lucky. It’s a testament to their faith, their reliance

that despite their profound losses, they consider themselves lucky.

Nepalese, the father and the group of NHS executives all laughed. I marveled at

how he could be laughing when fate has dealt him blow after blow: a child with

hemophilia, poverty, earthquake. There’s no self-pity, only perseverance and

reliance.

walk, through an open field that was actually refreshing in the mid-day heat,

and then through rice crops, startling green and lush, and then over a creek. I

had to jump across. For Barun, it was a challenge as he has contractures in his

joints. With helping hands from Ujol, the NHS general secretary and father of a son

with hemophilia, Barun made it across. We spied a steel, corrugated shed, just

like Binita’s, up ahead. This was Laxman’s temporary home. Inside, much the same

as Binita’s: hot, dark with a wet floor. Laxman’s wife was present, and sweetly

presented us with Mountain Dew.

of the poor never ceases to amaze me.

while, and took photos. I asked Laxman who was helping him rebuild his home.

With Laxmi (the program director of NHS) translating, he replied, “No one. I’m

doing it myself.” He works in the daytime at a desk job, then returns each

evening to lay bricks. All this was said without self-pity or arrogance.

|

| Puskar’s temporary home |

outside we caught Barun again having a smoke, and kidded him about his painkiller.

Though this time I think he really needed it.

through the rice fields again, and back to our trusty Land Rover. Our next stop

was to go to the school Puskar attends. It was a short drive, and an impressive

school. With 400 uniformed children, the school provided classes, recreation (including

a pool) and hot meals. American cartoon characters were brightly painted on the

faded yellow wall surrounding the school. Just inside the main gate, gaily

colored statues of Buddha, Shiva and Kali.

|

| Kali |

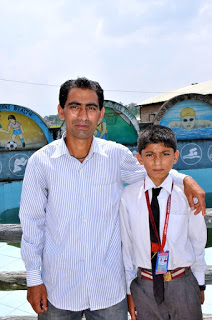

headmistress how she felt caring for a child with hemophilia at her school. “It

is fine,” she said in perfect English. “We welcome him. The father told us

about hemophilia, and we know what to do.” She added, in more measured tones,

“We do ask that the children not push him or hurt him. So he often does not

play as much as the others.” While she spoke, Puskar walked up, a gangly

11-year-old, all arm and legs, slim, with pale skin, and large eyes. I’m sure

he felt embarrassed being called out in front of his classmates, who were all

seated quietly under a canopy, eating lunch.

|

| Laxman and son Puskar |

pointed to the main building, which had visible cracks. “Normally we have class

in there,” she explained, “but due to the earthquake, we have to hold class

outside.”

Puskar waited patiently, answered some basic questions in English, which he is

studying. But I could tell he really wanted to get back to his classmates! We

excused him and he took off like a shot, with all of us admonishing him to slow

down! It did no good.

into the Land Rover and headed for the next house. This was in an area very

hard hit by the earthquake. Every single building had damage, and whole blocks

were nothing but rubble. The earthquake loosened the plaster, covering the buildings,

and the bricks tumbled out like a Lego set dumped from a box. It looked like a bomb had gone off in

the center square. In what used to be a park in the center were tents, and squatters

in the them.

A mother shyly

A mother shylytagged alongside me, holding a wide-eyed baby in her arms. She was dirty, thin,

but coy. I find the people are always surprised when you smile back and chat

with them. She was excited to make contact; her baby not so much, as he leaned

way back away from me. She lived in the tent now, and came from another village

that was totally destroyed. I thought ironically, we pay to go camping in

tents. Her life is now reduced to living in a tent like a refugee.

On to Danchi, Sankhu.

On to Danchi, Sankhu.We next arrived at the home of Achyut Shrestha, age 26, who wasn’t at home.

He’s a government employee now, and no longer in the Save One Life program;

another success! The tall, narrow brick home stood on a corner. The mother, a

short, dark woman in a flaming red sari, descended slowly down the stairs. She

gave us a namaste, and clasped my hands, so happy to see us. Her daughter was

also present, and warmly greeted us. They invited us in right away, something I

was not so sure we should do. Up the concrete stairs and ducking, entered the

small second story room. Cracks veined every wall, and fresh concrete had just

been applied to patch up some. It’s a poor home, and not livable. “We use this

in the day time to cook,” the mother explained. “But at night we sleep

somewhere else.” The government has condemned most of the buildings in town.

I’m not sure what will be the fate of everyone.

|

| Hospitality in the temporary home |

by Save One Life and the Mary Gooley Treatment Center (Rochester, NY) will help

pay for repairs. We walked down the road, out side the town, and saw sprawling

hills, green fields and small temples. Next to the temples, more tents; a half

naked baby boy toddled outside one of them. We smiled at his charm, but inside

felt sad about his condition. Down the road, around a bend, we came to another

part of town. The mother explained she was having a new house built. Sure

enough, a man, woman and young girl were busy laying bricks. There would be two

homes, in one building.

smiled shyly. “Because I have two sons.” I realize she wants them married with

their own homes. We all smiled.

Rajbchak family. Here live the parents and two young men with hemophilia,

Jagatman (age 25) and Jagatlal (nicknamed “Monsoon”). Monsoon was on hand to greet

us and was the only family member who spoke English, and not just English but

flawless English. He was charming and intelligent. To the left, the remnants of

his two-story family home. Half the house collapsed into the lot next to it. I

climbed the rubble heap to have a closer look, and down at my feet, amidst the

ruins, fresh, strong sprouts were shooting up. It reminded me of a quote from

Robert Frost when asked about the meaning of life. His response, “It goes on.”

The sprouts reminded me of the reliance of the Nepalese.

self-pity. How could anyone? They all faced the same problems. The boys’ father

appeared, a strong man, who is in the process of also singlehandedly building a

new home. It’s also a metal shed, but he is plastering the walls to make it more

livable. It’s much bigger than the other sheds. We stood inside for a photo.

We walked down the road to see our

We walked down the road to see ourmagnum opus: a mobile cell phone repair shop. Though humble by Western

standards, the shop was perched at a crossroads (perfect location!) and had an

open front that promoted watches, toys, picture frames and candy. Inside,

visible from the front counter, was a young man busily at work: Jagatman. He’s

rather famous to both Save One Life and Project SHARE.

to have his leg amputated, result of an untreated bleed. We quickly gave the

donation and the operation was a success. He has an artificial leg that enables

him to walk about without crutches. So here he is: 26, one leg, hemophilia,

with no home. He was busy at work, surrounded by all sorts of electrical parts,

wires and circuits. He knew what he was doing. Through Save One Life he

received a scholarship to get training in cell phone repair. Then, with our

mircrogrant, he opened his own repair shop.

I consider him a miracle, a marvel.

I consider him a miracle, a marvel.He has unending reservoirs of strength. He paused long enough to smile and

thank us, but got back to work. I think he wanted to prove to us that our

investment was well used!

man he has become, tired after our long day, and happy with this family’s

enduring success. The boys’ mother brought out fresh yogurt drink, which was

lovely after a long day with no food. We entirely forgot about lunch! At least

seven hours had slipped but without food.

Monsoon shared, “The shop is doing

Monsoon shared, “The shop is doingwell. We are making about $500 a month now. But we have to pay rent and for the

items.” Still, $500 a month is an astounding figure for Nepal, and for a

disabled person, and just after a major earthquake.

hands, gave our namastes, and waved good-bye. The long and bumpy ride back to

Kathmandu was punctuated with laughs and shrieks from the back seats: the young

people, Laxmi, Barun, Nirmal, were swapping stories and jokes. I didn’t know what

they were saying but their laughter gave me so much pleasure and hope.

|

| Jagatman and brother Jagatlal, who both have hemophilia |

|

| Jagatman’s store: a Save One Life success story! |