Kenya: Health is like the sun

Disease and disasters come and go like rain,

Disease and disasters come and go like rain,but health is like the sun that illuminates the entire village. Kenyan proverb

belief, it is not scorching hot but cool and pleasant, lush and green. It’s

winter here, and the mornings are moist and overcast, later clearing to blue

skies and mild temperatures. I’m in Kenya, in particular, visiting the children

and young men who participate in Save One Life, our child sponsorship program. We

work through our in-country program partner, The Jose Memorial Haemophilia

Society, established ten years ago by Maureen Miruka, mother of a child with

hemophilia. They’ve been fantastic to work with and this is my fourth or fifth

visit to Kenya, a country I’ve come to love. Over just two days we will visit

six families around the capital, Nairobi, and in Murang’a, a town about 90

minutes away from Nairobi.

bags, packed with gifts for the families (t-shirts, caps, toys, candy, school

supplies) and our hiking gear, for following this trip we will climb Mt.

Kilimanjaro as a fundraiser for Save One Life. In fact, as this is posted

automatically on Sunday, I have already started my climb by now!

raised $65,000 for Save One Life, for our Africa programs. Many people in our US

and global community asked if there would be another climb. Particularly, some

executives from industry wanted to climb, so we arranged a “CEO Challenge,” for

those captains of industry to not only climb, not only raise money for Save One

Life, but to experience a world vastly different from their own firsthand, at

ground zero. To experience, even for a day or two, the lives of the poor with

hemophilia in a developing country.

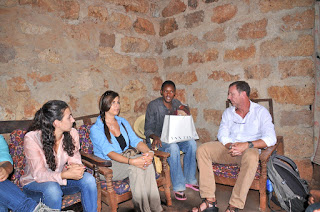

|

| Save One Life’s volunteer team with JMHS at Stanley’s home |

Our volunteers from the US are Eric Hill, vice

president and COO of Diplomat Specialty Infusion Group, formerly vice president

of BioRx, and his 15-year-old son Andrew. Eric serves on our board of directors

as treasurer and has been invaluable for his expertise and dedication. He

sponsors 31 children! Eric climbed with me in 2011 with his son Alex. Eric and

I know exactly what kind of suffering we are in for! We also have Rich Gaton,

co-founder and president of BDI Pharma, a specialty distributor that provide

hemophilia and other therapies since 1995. Rich’s company is a proud member of

Save One Life’s Dedication Circle, sponsoring 20 beneficiaries over the past

eight years. With Rich are his wife Wendy and two daughters, Taylor (20) and

Samantha (16).

commercial operations for Aptevo Therapeutics, Inc., a new company spun out of

Emergent BioSolutions, manufacturers of the recombinant factor IX product

Ixinity. Joining us on the Kili climb is Jim Palmer, MD, a surgeon from

Philadelphia and friend of Mike’s, who is also

fundraising for us!

by Maureen Miruka, our long-time colleague, founder and president of the Jose

Memorial Haemophilia Society, dedicated in memory of a son she lost to

hemophilia. The JMHS is our program partner in Kenya, and through it we sponsor

47 children and adults with hemophilia, with two more registered and waiting to

be sponsored. With her were Sarah, the office administrator, a quiet and lovely

recent college graduate, with beautiful eyes and cascading braids. Maureen

whispered to me, “Sarah is a godsend. She is efficient, responsive and

intelligent. I want to keep her on!” And the charming, energetic and gregarious

Kehio Chege, father of a child with hemophilia, and board member of the JMHS.

|

| Maureen Miruka, president of JMHS, Jane Mugacha, pediatric nurse and Sarah Mumbi of JMHS |

We loaded up the two safari style vans with gift

bags, our cameras and water, greeted our “pilots” (drivers) with a quick jambo (hello), hopped in and drove off.

Navigating the Nairobi traffic, we had time to chat about our mission and

hemophilia in Kenya. Maureen provided background on herself to the group, how

she founded her society, and plans for the future.

its estimated 3,000 patients. Treatment is centralized at the Kenyatta

Hospital, the large public hospital in Nairobi. Project SHARE, operating from

my company, LA Kelley Communications, has provided factor for Kenya over the

past 15 years, as has the World Federation of Hemophilia. We continue to

provide factor to both the JMHS and the Kenyatta National Hospital. Of the estimated 3,000 with

hemophilia in this country of 44,000, only about 500 have been registered. Of

the 500, only about 150 are “regulars,” that is, we know who they are and where

they live. The others are what I call transient patients: they may have visited

the hospital once in their lifetimes, or have visited a few times, but not

regularly. In developing countries, people move about frequently, sometimes

living with relatives in different towns, villages or addresses in the cities,

as they struggle to make ends meet.

poor. These are the ones enrolled in Save One Life, a few of which we would

visit today.

fresh fruits like papaya, watermelon and bananas, managed by women in colorful

clothing. City fell away to countryside in no time. The tall buildings and

billboards of Nairobi transformed into banana trees, tea plantations and

rolling hills. Kenya is beautiful, like so much of Africa. The climate and

topography, the images and animals all have captured the attention, dreams and

affections of visitors.

Murang’a District Hospital, to meet with the hospital chief, tour the wards and

offer a gift of factor. Jane Mugacha, nurse and our main contact there, showed

us the pediatrics ward (“My home,” she said, holding her hand to her heart),

where a small refrigerator held a few vials of factor. “This is where the

patients come to get infused locally,” she shared. Murang’a is 90 minutes from

Nairobi and so it is far better to store factor here. This sounds

logical, but trust me, in developing countries most hospitals have no

factor except the main government ones in the capitals. Patients have to travel

hours, sometimes days, to get treatment for bleeds that by then have already

done their damage.

|

| Wendy Gaton with Stanley |

factor was stored, when back home, their inventories were chock full for the

insatiable American hemophilia market. We donated about 30,000 units, more than

tripling her current stores. Jane was ecstatic, effusive in her praise, for

just this small amount!

“waiting room,” of the hospital: wooden benches outside under a steel-corrugated

roof, overlooking an unpaved, red dirt parking lot. And people wait and wait;

the hospital is always busy, always crowded.

|

| Stanley’s farm |

15 minutes away we arrived at Stanley’s home. I last visited Stanley in 2011,

and he was in a new packed-mud home now, on his mother’s property. Stanley has

hemophilia, is rail thin, and rather somber at first. (This would all change

after an afternoon spent with Kehio and our guys.) We hiked down a dirt path

bordered with sprouting vegetation, leaving the drivers and our safari jeeps on

the road. Everything is red—the dirt, the mud structures— and green—the tall

grass, the banana plants, the papaya trees. Beyond the rusty colored home were home-made

wooden pens for farm animals: two mud-covered cows for milk, a few goats, and some

chickens. Stanley looked good since the last time I had seen him, walking, even

though his gait is a bit hobbled. This was my third visit to his home. Since

that time a new child had been born, a boy, who was now almost five. He stared

at our group with wide eyes.

|

| Stanley |

even older than his years), but he was the recipient of a micro-enterprise

grant. Stanley shared how farming took a huge toll on his joints and caused

bleeds. He had to hoe, hack, pick and carry crops to be sold at the markets.

It’s backbreaking work for someone with hemophilia. Save One Life had given him

a grant to start a shoe vendor business, selling shoes at the market instead.

It didn’t work out as he had hoped, and with the money left he instead bought a

cow. He now sells milk daily to a local school. He earns only about $50 a

month. We visited the cows in their pen, and Maureen, who has a PhD in Agricultural Research and Development and also is Director of Agriculture and Markets for CARE USA,

questioned Stanley on the condition of the cows. Their hip bones and ribs jutted

from their paper-thin skin. Dried mud dotted the flanks of one cow, and her

hooves stood deep in feces. Behind her, bordering the woods, a mountain of

manure. All very unsanitary.

Our main question that day: what do you need?

Our main question that day: what do you need?Stanley didn’t hesitate: concrete, to build a safe and slanted platform for the

cow to stand, to separate her from the manure, and to make it easy to wash off

the manure and mud. Rich Gaton, ever the man of action, asked how much and

when? I love it! We could make an immediate and concrete difference, no pun

intended, in Stanley’s life today. It’s what Save One Life is all about.

and Maureen promised to get back to us with an estimate for building a concrete

platform. Samantha and Taylor, cow lovers like me, wanted vitamins as well for

the cows. At the very least, a vet should look in on them.

|

| Derrick |

Stanley accompanied us. When Eric, Maureen and I last saw Derrick, he was two,

and had an enormous, disfiguring hematoma on his forehead. We thought it was

only a hematoma, but Maureen told us this day we were wrong; it was a

psuedotumor. Pseudotumors are not seen in the US for hemophilia. They are pulpy

masses of blood created from repeated, untreated bleeds into one area. Blood

vessels grow and entwine within this mass, making it almost impossible to

operate on without clotting factor. The patient could easily die. Derrick was

lucky; there was clotting factor available, and surgeons at Murang’a removed

the offending mass. Today, he wasn’t home at first, but his grandmother,

Virginia greeted us like we were family, and long lost relatives at that. I was

late joining the group as I ran back to get our bags of goodies from the car. When

I arrived, tripping down the dusty path and onto her farm, she saw me,

recognized me and despite her advanced years, crouched down like a tiger, arms

sprung open and flew at me. We embraced and squeezed each other tight. Then she

immediately launched into a lecture about my weight: why was I so skinny? “Like

you!” I replied. She grabbed me tighter and we laughed. Wow, she is strong!

Our group looked about her small, contained farm,

Our group looked about her small, contained farm,noting the healthy looking cow, goats and chickens, so different than

Stanley’s. We shared our gifts with the children there, including Tootsie Pops

and balloons. You cannot imagine the joy a simple balloon brings to children

who literally have no toys, not even a crayon. The bright blue and red balloons

contrasted with the earthy colors of the little farm and homestead. The

children chased the balloons and it gave our group a great way to interact with

them. All shyness vanishes when there is a balloon to toss around. I gave

Paris, Derrick’s five-year-old cousin, a teddy bear from my mother, and she

instinctively and promptly tied it to her back in the fashion of African women

who carry their babies on their backs.

|

| Virginia and Susanne |

Virginia chattered with animation in her delight to see us. She really is a

funny woman. She looked at Rich and Wendy’s two beautiful daughters with a

critical eye, and wanted to know immediately if they were married. They are

only 16 and 20! When she learned they were not, she said in Swahili, “You will

find a husband here!” and we all laughed.

your wife?” No boundaries with Virginia!

Kenyan woman, quiet and demur, holding one-year-old Susanne on her hip. Derrick

then returned home from school, and shyly greeted us. For life on his simple

farm, seeing all these muzungus

(white people) was a surprise!

Derrick had grown tall. And the only remembrance

Derrick had grown tall. And the only remembranceof his disfiguring pseudotumor was a small, orange scar on his forehead. His

joints were in good shape and he was happy. We shared more toys with him,

learned about school, and played outside a bit with him. All the while we

assessed the condition of the home, farm animals, children, and school

situation. Maureen was concerned about the apparent ring worm on Derrick’s head.

back up to the dirt road, and to the safari jeeps. But Virginia’s mother wanted

to say a prayer for a safe journey, especially up Kilimanjaro. We all bowed her

head as she prayed in Swahili for our safety. Then the children besieged us for

more candy and balloons. I will always remember to travel with balloons from

now on. I forget how easy they are to transport, and how much children enjoy

them.

|

| Laurie Kelley and Peter |

far down the road, and a new place for Peter, who moved into his uncle’s mud

home with his mother Jane and brother Zakayo. His story is poignant: impoverished, no father,

both brothers have hemophilia, and Zakayo suffers from what sounds

like bipolar disorder. The last time we were here, Maureen and I visited Zakayo in

Mathare, the psychiatric hospital in Nairobi. What a sad visit that was; the

wards are bare of anything warm or home-like. By 8 pm, all

the young men are drugged to be quiet and left to sleep on army cots with only a

thin blanket. Zakayo was left there because Jane couldn’t afford to pay his

bill. Without payment, patients are kept until it is paid, sometimes months. In

the meantime, the bill grows… it’s a vicious circle. We paid it and got him

home that night.

Pulling over on the dirt embankment, we

Pulling over on the dirt embankment, wedisembarked and saw Peter, tall and thin, not changed much since 5 years ago.

He has the sweetest face and disposition. We shuffled down a short hill to his

uncle’s home, where they all lived. Like most patients, they have a mud-packed

home, dirt floors, no windows, no inner lights, and a steel-corrugated roof. We

crammed in and chatted with the handsome, soft-spoken young man. Yes, he had

finished school, thanks to a scholarship from Save One Life. He is waiting now

for his grades, and will receive a certificate in electrical engineering. His

goal is to secure an “attachment” (internship) with a company and maybe get

hired. Then, if all goes well, open his own repair shop. These are practical

and doable goals and we were pleased to know he had a plan. His health has been

good, though he did miss time from school due to bleeds. He explained to our

group how painful the bleeds can be. “I did not sleep for two nights due to the

pain,” Peter recalled. “It was during exam time and so it was difficult to

focus on school.” As he spoke I could see sympathy register on Wendy’s face,

and those of her daughters.

We shared with Peter that we had some factor just

We shared with Peter that we had some factor justfor him. We could store it at Murang’a Hospital and he could go there to get

it. He wondered if we could possibly get him a fridge, to store the factor at

home. Eventually he will learn to self-infuse. At first we declined; it’s not

his home and maybe they would be asked to leave? Perhaps the uncle wouldn’t

allow the fridge to go with them?

wanted to do something now. I love

that attitude! We discussed the fridge with Maureen and Kehio, and they agreed at last. I turned to

the guys—Mike, Rich and Eric—and asked if they could change Peter’s life for

the better right now? Not a problem. Out came $200 and we gave it to Sarah. She

would return in a few days with the money, and shop with the family at the

market, to ensure the money is used for a fridge.

now have factor in his home, an incredibly rare thing in Kenya. He’s our hope

for the future.

Zakayo appeared, on crutches. He looked preoccupied, as if in pain. I hopped

out of the jeep, gave him a hug, and asked if he remembered me. He did. Jane

started pulling up his pants leg to show me his wound, a deep gash in the shin,

bleeding through the bandages. Zakayo wanted money, to start a stand to sell

items, possibly fruit, but due to his condition, we didn’t think this was a

good idea. We’d rather support the mother or Peter, who in turn would support

him. He seemed crushed with this answer, and backed away. I wish we could help

each child, but sometimes we cannot.

Still, it was a productive day with many

Still, it was a productive day with manymemories. To each family we pooled our money and gave a cash donation equal to

about half of all their monthly income, just to ease their burdens, which

are many. And each in turn gave us a gift: a huge stalk of bananas, or a bag of

maize, a hug. But the best gift of all was their permission, to allow us to help

them, to allow us to share their world, so different than our own.

through this journey called life.

More stories next week, after our Kilimanjaro climb!