The Day of Living Dangerously: Haiti

The rocks in the water don’t know how the rocks in the sun feel.—Haitian proverb

Haiti is the poorest country in the Western hemisphere, and even during good times is never easy to visit or work in. A government that seems perpetually corrupt, combined with natural disasters (most notably the earthquake of 2010), difficult topography, lack of infrastructure, and massive inflows of foreign aid have left this island nation dependent, poor and frustrated.

The frustration reached a peak last week, when riots erupted in the capital, Port-au-Prince, and the second largest city, Cap Haitien—right where I was. I flew from Boston on Sunday, February 10, after at least 7 months of planning, and 16 years in the making. At last, I was going to start a hemophilia program in the country. Yes, 16 years in the making. That’s a story for another blog.

I landed on Sunday and was home Monday night. Only 24 hours in Haiti. Almost all our plans foiled. But it was not a total loss. I was able to meet two of the 11 boys I know with hemophilia. And that made the whole adventure worthwhile.

I met up in Miami on layover with Barbara Campbell, executive director of the Dalton Foundation, which does a lot of great health care work in Haiti. Her group is connected with the Cap Haitien Health Network (CHHN), a nonprofit based in Orlando, which has guided me for the past 11 years in trying to establish hemophilia care. Barbara is competent and energetic, and obviously loves Haiti.

This is the irony of Haiti: as bad as it gets, as frustrating as it can be, there is something compelling about the country and its people, especially to Americans and American missionary groups. Perhaps because it is only a 90-minute flight from our shore: we feel a kinship with this sad piece of earth. Perhaps it’s because we know there must be a solution; I mean, it’s a tiny country—how hard can it be to fix? It’s right in our backyard. Let’s bring in the help, the food, the seeds, the money, the medicine, the manpower—let’s fix this place up! It hasn’t quite worked out. For all we have invested in Haiti, it festers in the heat. And still we want to make it the beautiful country it should be.

Two hours later, Barbara and I landed in Cap Haitien, and were met by our driver, “Charles,” who also happens to be a lawyer and CPA. The day was sunny and surprisingly dry, and I looked forward to an afternoon with two brothers with hemophilia. But Charles told us we were not going to the hotel first, as planned; it would be too dangerous to drive in and out of that area twice. There were roadblocks and bonfires in the streets, and protests. Better to go see the boys now, and make only one trip into the gated Hotel de Roi Christophe. We piled all our luggage (mostly gifts) into the small van and took off. We got lost a few times, but it was a quick 30 minute ride to the boys’ home. The roads were worn and torn, and traffic was light. We got lost a few times but finally pulled up to a quaint, deep turquoise-colored single level house on a packed dirt road.

See photo gallery of trip here.

There to greet us is June Levinsohn, an American from Vermont, who has worked in Haiti for 30 years and speaks fluent Creole. Spry and direct, June is one of the most dedicated people I’ve ever met, and her dedication and knowledge gives her the right to be honest and blunt when speaking about Haiti. And it was June who helped put us in touch with the two brothers. June saw a photo of Steven Saintil in the Coastal Haiti Mission newsletter back in early June. No one seemed to know what was wrong with the child with the swollen knees in the photo, but June asked Dr. Ted Kaplan of the CHHN, who then referred the child’s case to me. Looking at his knees, we all suspected hemophilia. In an extraordinary feat—keeping in mind none of us had even met—we had Steven’s blood drawn and flown into Miami, where a pathologist I know picked it up and diagnosed Steven with severe hemophilia A! And Project SHARE began sending factor to him last September, via his local doctor.

There to greet us is June Levinsohn, an American from Vermont, who has worked in Haiti for 30 years and speaks fluent Creole. Spry and direct, June is one of the most dedicated people I’ve ever met, and her dedication and knowledge gives her the right to be honest and blunt when speaking about Haiti. And it was June who helped put us in touch with the two brothers. June saw a photo of Steven Saintil in the Coastal Haiti Mission newsletter back in early June. No one seemed to know what was wrong with the child with the swollen knees in the photo, but June asked Dr. Ted Kaplan of the CHHN, who then referred the child’s case to me. Looking at his knees, we all suspected hemophilia. In an extraordinary feat—keeping in mind none of us had even met—we had Steven’s blood drawn and flown into Miami, where a pathologist I know picked it up and diagnosed Steven with severe hemophilia A! And Project SHARE began sending factor to him last September, via his local doctor.

And here we were now, with Steven! Although 11, Steven is small, but I am happy to say his knees look a lot better than before. With the factor donations, he was able to return to school, which is just down the road. It’s a Christian school, and Pastor Cody, who looks out for Steven and his half-brother Louvens, was with us that day.

Steven and Louvens knew who I was, and I interviewed them a bit. The father of each boy is gone, disappeared, not wanting to deal with a sick son. The mother is dead; she died from a parasitic infection six years ago. “The doctors pulled a worm out from her,” June shared, “that was working its way out of her body through her arm. Her infection was too far gone by the time she sought help.” The boys are now orphans technically, and live with their aunt. The aunt has a small son as well. The house was neat, with furniture and a toilet—which surprised June—but it was not functioning. Concrete walls and floor, lots of dust, but lots of vegetation to give it a more cultivated look.

Steven and Louvens knew who I was, and I interviewed them a bit. The father of each boy is gone, disappeared, not wanting to deal with a sick son. The mother is dead; she died from a parasitic infection six years ago. “The doctors pulled a worm out from her,” June shared, “that was working its way out of her body through her arm. Her infection was too far gone by the time she sought help.” The boys are now orphans technically, and live with their aunt. The aunt has a small son as well. The house was neat, with furniture and a toilet—which surprised June—but it was not functioning. Concrete walls and floor, lots of dust, but lots of vegetation to give it a more cultivated look.

The boys look clean, well fed, and happy. And happier still when I opened the duffel bag filled with toys donated from uniQure! I had asked the boys if they had any toys, and they shook their heads. Pastor Cody said, “They find things to play with—a tire, a stick.” Now they had pads of paper, markers, Black Panther coloring book (kudos to whoever donated that! Huge hit), small soccer ball, more coloring books, backpacks, soap, toothbrushes, cold packs, crayons, Matchbox cars (small war waged over who would keep those), and more. Now the boys smiled widely and really warmed up! I had also printed out a photo of Steven using a walker; the photo fascinated the boys. Now Steven was walking better, but damage had been done. His hip now thrusts out to overcompensate, which could lead to problems down the road. We will need a PT in soon to help teach the local PTs how to correct this.

Due to the escalating violence, we had to cut our visit short. With high fives, we said goodbye, and piled back into the van. June was staying with friends, and Barbara and I headed back to the hotel. As we neared the center of Cap Haitien, a scene as horrifying as the riots appeared. Absolute mountains of trash undulating on the beach. Cap Haitien sits on a bay, where fishermen catch their daily wages in handmade dugouts. They were barely visible in the bay due to the heaps of trash. I’m used to seeing trash on the street in developing countries but this range could have its own name and topography. Colorfully dotted with ubiquitous blue and pink plastic bags, the everything in their way.

Turning a corner towards our hotel, we could see the smoldering ashes of where the bonfires had been that day. A UN Peacekeeper tank rumbled by, startling us as we took a right, and police cars patrolled. The crowds were mostly dispersed—it was suppertime—“But they will come back tonight,” Charles warned. “Do not go out.” He rocketed at high speed, crushing through one faltering barricade and dodging others, to reach the hotel gate, which was locked. “I’ve stayed here many times,” said Barbara, “And they never lock the gate…”

At the hotel, Barbara and I checked in; though run down, the hotel was pretty. There were large cracks in the concrete walls and foundation, and desiccated leaves cracked under our feet. We had a delicious dinner and shared our personal stories—hers was fascinating! And then returned to our rooms to check email.

Not long after dinner, Barbara poked her head into my room and said, “We have to leave.” The riots had escalated in Port-au-Prince, and rumor had it that Cap Haitien would explode as well, especially if guns entered the equation. While it might not happen tonight or tomorrow, riots later in the week might mean the airport would shut down. The airport is small, and has almost no security. We had meetings scheduled the next day with the Cap Haitien Health Network to introduce hemophilia, and then a 5 hour road trip to Port-au-Prince, and then the finale—after 16 years of searching, a meeting with what might be our first HTC in Haiti.

None of it was to be on this trip. We booked the next flight out of Cap Haitien, Monday at 1:35 pm, about 24 hours after landing. As surreal and foolish as it all felt—after all, there was nice Caribbean music coming from the bar in the lounge, and birds hawking overhead in the tree—the situation could turn on a dime. Our colleagues in PAP confirmed it; meeting cancelled, and the US Embassy was issuing advisories and warnings not to travel to Haiti, and for Americans to leave.

The next morning, we packed quickly—I had barely unpacked—and Charles came early to take us to the airport. At 8 am, as we turned down the street, we encountered the first demonstrators. A bonfire raged in the middle of the street as a crowd gathered. About 50 feet away, an angry young man in a red t-shirt spied us and hurled a rock at our windshield. Others got ready to throw and we heard the rocks pelting around us. Charles bravely leaned out and shouted in Creole, waving his arm. The man seemed a bit startled and confused. Luckily, we were hidden a bit in the back seat, our windows darkened. Though I badly wanted to take a photo, I knew this could attract the anger of the crowd too.

The man waved us through. We sped to the airport and in 15 minutes were there. We were the first to arrive. Eventually the American Airline agents showed up, and had to hand write our boarding passes. In Haiti, anything goes. From there, our lives went on smoothly. We checked luggage, boarded the plane, connected in Miami, and separated to our homes.

The man waved us through. We sped to the airport and in 15 minutes were there. We were the first to arrive. Eventually the American Airline agents showed up, and had to hand write our boarding passes. In Haiti, anything goes. From there, our lives went on smoothly. We checked luggage, boarded the plane, connected in Miami, and separated to our homes.

For those in Haiti, they were home, which was descending into a dangerous madness.

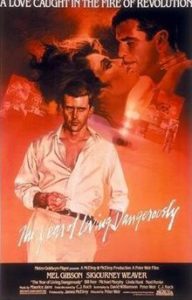

On the flight home, I watched my favorite movie, The Year of Living Dangerously, starring Mel Gibson, a 1982 movie about a journalist covering the deterioration of Indonesia in 1965 under a corrupt government. There were a lot of parallels with what I was witnessing, including the last scene, where Gibson’s character escapes the madness and poverty, and heads for London. I couldn’t help but feel guilty, knowing what I was leaving behind me.

June shared with us a message from a friend in Haiti last week: “The food and water crisis is already upon us — not so much [where we are] because we still have rice and are able to buy some beans. So the kids are still getting their one meal a day. But in the surrounding community people are already going whole days or more without food either because the markets are closed or even when the markets have food, they don’t have the money to buy it. The price of food has almost doubled since this began (and, because the value of the Haitian gourde has plummeted this year, the prices were already higher than normal).” And since then, riots have worsened in PAP, and people have been killed.

We will return to Haiti and resume; we’ve come too far and actually have a foothold now with hemophilia care. Pray for Haiti, and its people. They have suffered too much to stop now. We will continue to send factor to the boys we know. I have a registry of 11 boys with hemophilia, and am the only one who knows who they are, and where they are. I had hoped to transfer this knowledge to the local teams and start the first national registry. So I must return. And want to return.

See complete photo gallery of Haiti here.