Laurie Kelley

March 9, 2020

It was 1989. My son with

hemophilia was two, and we had had some experiences with bleeds. There was the

potential head bleed at nine months, when our baby was sitting up but still

wobbly, and pitched backwards and hit his head on the hard wood floor. We

rushed him to Children’s Hospital for his first infusion. I was crying more than

him, and was ordered out of the room, while our nurse tried to secure a vein. I

wandered the hospital halls, crying to myself, and when I returned, saw

everyone, including my baby, laughing and just fine. That’s when it dawned on

me that I had more problems with the infusion than my baby!

There was the bleed at age 10

months, when our son stood up in his crib. He was teething and gnawed on the

crib railing. I saw blood dripping from his mouth and realized he had cut his gums.

But suddenly the bleed stopped! He was moderate, after all, and perhaps the

bleeding would stay stopped. I put him down to sleep.

In the morning, I opened

his door, and there he stood, one little hand on the crib rail, and one holding

his bottle, covered from head to waist in blood. Only his round white eyes

seemed visible. He was smiling a grisly, bloody smile. If I hadn’t known it was

from a small cut in his gum, I would have panicked. This time I remained calm,

and cleaned him up as best I could. Blood was in his ears, hair, nose… everywhere

and the gum was actively bleeding now. So back to Children’s Hospital for an

infusion. We had to wrap him in a bedsheet to sneak him out of the house. We

lived in Medford, Massachusetts, a town where the houses are crammed together and

where there is no privacy! We spent the morning at the hospital, and he got a

second infusion.

When sharing this story,

now with a bit of humor, at our monthly parents’ support group meeting, one of

the moms asked if we had used Amicar. Never heard of it! She was surprised, and

we were surprised. Amicar helps neutralize saliva so that it won’t break down a

clot in the mouth. Why had no one at Children’s told us about this? Had we

known, and given him a dose that first night, when the bleeding stopped

temporarily, maybe we could have avoided a hospital visit and infusion.

It dawned on me that

parents have first-hand knowledge and advice that maybe even the medical team

doesn’t know or remember.

We remained tethered to our

HTC. The turning point came September 29, 1989, when my son had just turned two.

It was like a new me was born. An advocate. A real hemo-mom!

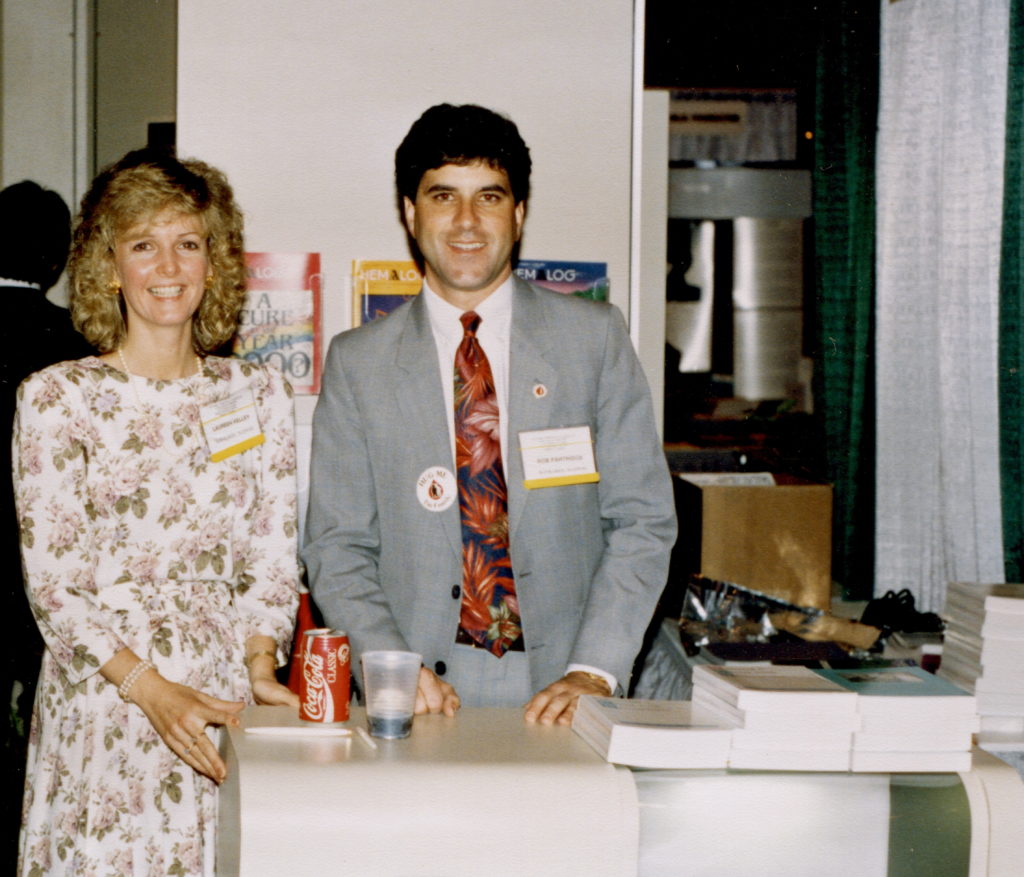

I will never forget that

morning. I was dressed up to go to work (it was the ‘80s!): silk dress, big

hair, big earrings, jewelry, and high heels. I worked at DRI/McGraw-Hill, a

private economic forecasting company. My dream job. I worked with intelligent,

interesting people creating and delivering economic forecasts for different

industries. I felt at last everything was going great and hemophilia was under

control. That all would change.

Wearing those high heels, I

drove my son to the babysitter, as usual. Carrying him from my car to the front

door, I slipped on something, Maybe mulch, a stone… who knows? The baby pitched

forward from me, and landed headfirst on the driveway. Our babysitter cried, I

cried, the baby cried. I put him back in the car and we rushed to the hospital.

My husband met us there, after the sitter called him. Imagine, no cell phones!

I recall waiting and waiting at the hospital.

No infusion at first, just x-rays, and many doctors standing around discussing

what should be done. We waited hours. No food, no juice, and finally, no

patience. My son, who had been running around the hospital halls, started to fuss

and cry. A nurse tried to pin him down on a table for an MRI, but my son would

have none of it. She said, “I’m going to get a doctor to help hold him down.”

My husband looked angry (and he never did), and frustrated. We talked about

what was happening, and I said, “Let’s get out of here.”

It seemed radical, controversial. We

were saying we were leaving the hospital without approval. The team had finally

infused him, but were not making any decisions about next steps. And our son

hit the breaking point. We knew the symptoms of a head bleed. We could monitor

him. So we announced we were leaving, and were told, No you can’t! Yes, we

could. And somehow I knew I was right.

We signed a stack of papers, and left. All

weekend we monitored him, and into the next week. He was fine. No sign of a

head bleed.

When I shared this episode with our support

group, our nurse Jocelyn made the suggestion that perhaps I wanted to write this

down? I guess I sounded emotional, and she might have felt I needed to sort out

my feelings. But I actually was feeling very empowered. I had made a medical decision.

I could make decisions about my son’s health. It was a revelation. I was a

person who seemed to escape all physical problems as a child; the worst thing

that happened to me was getting stitches in 5th grade. I had no experience

dealing with hospitals and doctors until I actually had my baby. It was a revelation

that I could make this medical decision.

So I started writing. But I also remembered

all the wisdom I had heard in the parent support group. I started writing that

down. Little by little, the writing exercise became something more. What if I

were to ask parents of children with hemophilia to share their stories? How empowering

would that be? I know I needed their information and advice.

I called the National Hemophilia Foundation

and asked the advice of two women who worked in their educational department.

They were adamant: a book would be a great idea, but not just stories. “We want

a guidebook,” said one of the women. “At each stage of life,” added the other.

That was a lot more than I had originally

dreamed up. But why not? A book about how to raise a child with hemophilia,

based on advice from parents. I had a degree in child psychology and had

published research. I knew how to research.

The book idea became even more urgent

when I learned there was not just one brand of factor, and one homecare

company, as I was led to believe. I had a choice. And I was a consumer, not just

a patient. I could make my own decisions there too. My husband knew all about

the medicine, because he worked in the field. We could include a whole chapter on

being a consumer.

The book idea became a reality, a

passion, a need. Now all I needed was a way to solicit stories… and get

funding.

Next: Phone calls pour in, and one

postcard turns the tide.