I’ve just returned from an amazing three-week trip to the Arctic. Specifically, a transpolar trip: from Spitsbergen, Norway (the highest human settlement in the world) to the North Pole, then down to Nome, Alaska. As this was as much a scientific trip as leisure, I studied for months about polar exploration of the Arctic in the 1800s and 1900s. Polar exploration is a passion of mine, and this was a chance to see the barren, hostile yet beautiful world seen by the early explorers.

Yet as of 1926, no one could definitely say what exactly was at the North Pole. Was it all water? Was there an ice cap? Was there land?

The North Pole was considered the last geographic trophy to nab. A million square miles that no one had seen; a huge blank space on the map at the turn of the twentieth century.

There were long and painful dog sled voyages, and sea voyages. The names Nansen, Amundsen, Peary and Cook go down in history.

But a major development was using airplanes. Imagine flying to the North Pole! And if one did, would there be enough fuel to return?

The birth of aviation is intrinsically linked to attempts to reach the Arctic. Besides dogsled and sailing ships, airships (dirigibles, or “blimps”) had been tried in 1897, first by a Swedish engineer, S.A. Andrée, which ended early and in the deaths of those on board, and then by American journalist Walter Wellman, on the airship called the America, in 1907 and 1909. This didn’t work either, though Wellman went on to live his life as a famous and successful journalist.

The “Great War”—World War I— accelerated the development of aviation, and fostered the idea to fly to the North Pole. By then Dr. Frederick Cook claimed to have reached the Pole in 1908 by sled, as did Robert Peary in 1909, but both claims were disputed and later refuted.

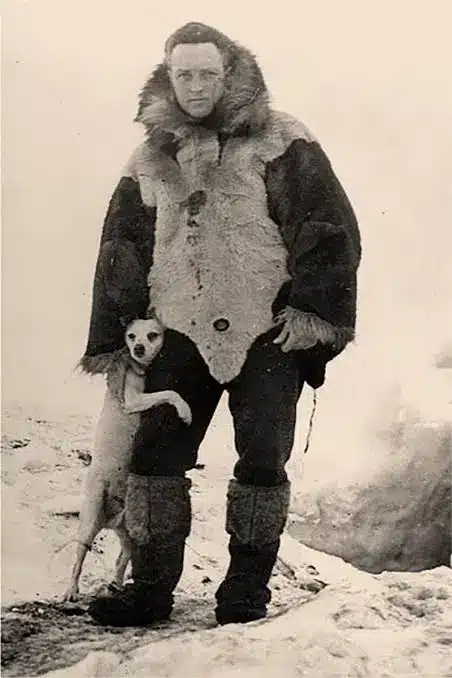

Admiral Richard Byrd proposed to retrace the route Peary had taken to the pole, but from the air. By March 1925 Byrd had a plan: possibly landing a seaplane in the Arctic pack in July and August and refuel, something that had never been done before. This was exciting, as aviation to the Arctic could open new trade routes, vital to world economy. And if Byrd found land, the U.S. could claim it.

He had competition. Norwegian Roald Amundsen was the famed explorer who had already been first to the South Pole and through the Northwest Passage. The Norwegian had already tried flying to the Pole, using two huge, all-metal flying boats made by Dornier, a German manufacturer. On May 21, 1925 Roald Amundsen and Lincoln Ellsworth took off from King’s Bay, Spitsbergen. I was privileged to see the place where they departed. One plane crashed, though all the men survived. They spent a month on an ice floe, with no radio contact, but cleared a crude runway and flew their last plane back with all the men on board. It was heroic.

Then it was Richard Byrd’s turn. By 1926, Byrd also planned to reach the Pole by plane.

Meanwhile, Amundsen had not given up. He prepared to reach the Pole by airship, in the Norge (Norway). They would actually take off within days of one another, from the same place—Kings Bay, Spitsbergen, Norway. Who would make it first?

What surprised me, reading about the race to the Pole, was learning that a thirty-five-year-old Dutchman named Anthony Herman Gerard Fokker, who became rich equipping the “Bloody Red Baron” von Richthofen during World War I, took his company’s top single-engine monoplane, the “F-VIIA,” and added two more engines to make it the “Fokker trimotor.” It was the first airplane out of seventeen to return to Ford Airport in Dearborn, Michigan during a seven-day, 1,900-mile promotional flight sponsored by Edsel Ford.

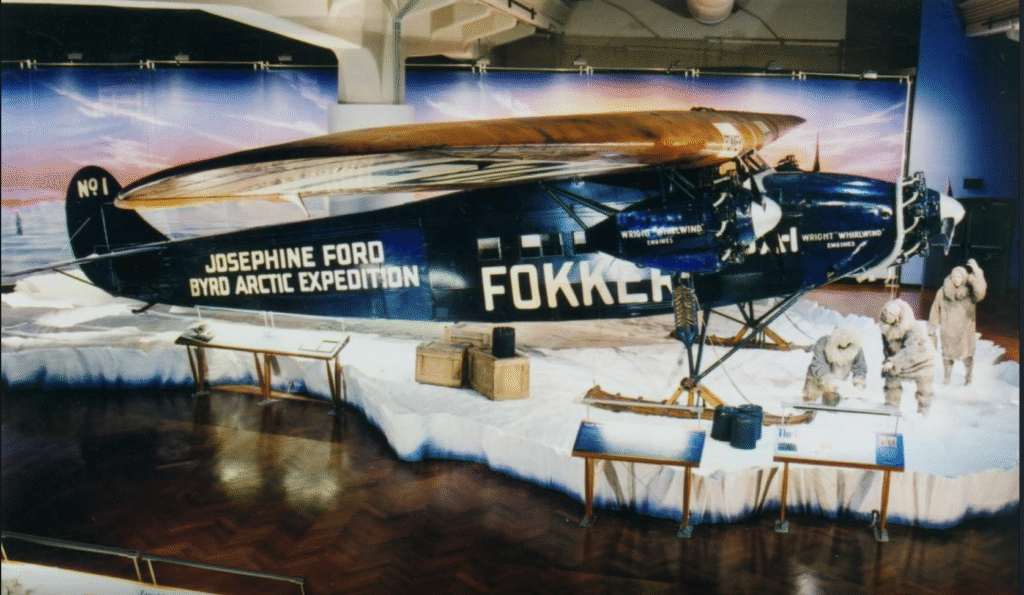

Byrd was friends with Edsel Ford, but had to purchase a trimotor from Fokker for his Arctic expedition after a fire at the Ford plant. The range of the trimotor was only half that of Amundsen’s dirigible. Byrd purchased a “J-4,” and Fokker installed the same trimotor used in the Ford promotional tour. Despite buying the engine from Fokker, Byrd honored Ford, his chief benefactor, by naming his plane for the third of Edsel’s four children—his only daughter, three-year-old Josephine. “JOSEPHINE FORD” was painted above “BYRD ARCTIC EXPEDITION” on the fuselage, along with “FOKKER.”

While Byrd completed his roundtrip to the Arctic on May 9, 1925 under incredibly difficult circumstances, he was not awarded the prize of claiming the Pole. It was difficult to measure accuracy under the conditions. Instead, the prize went to Amundsen, who flew for Norway in the Italian-made dirigible Norge, and who was able to say definitely, once and for all, that he reached the North Pole. This is acknowledged in history now.

But think of it! Byrd, a U.S. Navy admiral, engineer, and pilot, flew a plane to the North Pole with a trimotor that used the same nomenclature used for the groundbreaking, life-saving medicine infused by people with hemophilia and inhibitors—Novo Nordisk’s NovoSeven, activated factor VII, shortened to FVIIa.

Photo credit: The Josephine Ford, from the Collections of Henry Ford