You Should Donate Blood (But Not Like This)

I missed promoting National Blood Donation Week, which was September 1-7. And International Plasma Awareness Week (IPAW) just ended and was held October 3-7. This is promoted by the Protein Plasma Therapeutic Alliance (PPTAglobal.org), which is also involved in hemophilia. There are still factor products made with human plasma, so it’s always good to donate!

But don’t think it’s like the following donation story! I love reading about medical history, especially about the men and women who discover cures and breakthroughs. One of my favorite stories is the history of blood, particularly how physicians and researchers employed it and through research and trial and error, learned how to properly transfuse. And since I wrote about vampires and vitalism (sort of like a blood transfusion!) last week, let’s visit this story.

The ancient Greeks saw all phenomena as the result of the interaction of four elements: air, fire, wind, earth. In the body, this manifested as “humors”: phlegm, choler, bile, and blood. The Greeks believed good health meant maintaining a balance in the humor, so draining blood (“blood-letting”) and purging the digestive system should help restore balance.

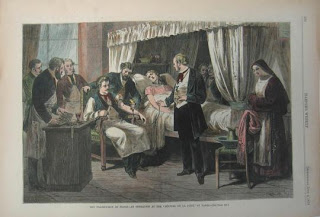

One of the first human blood transfusion first took place in Paris, in the 17th century. It took a wild and undiagnosed insane man, Antoine Mauroy, to help change the course of history.

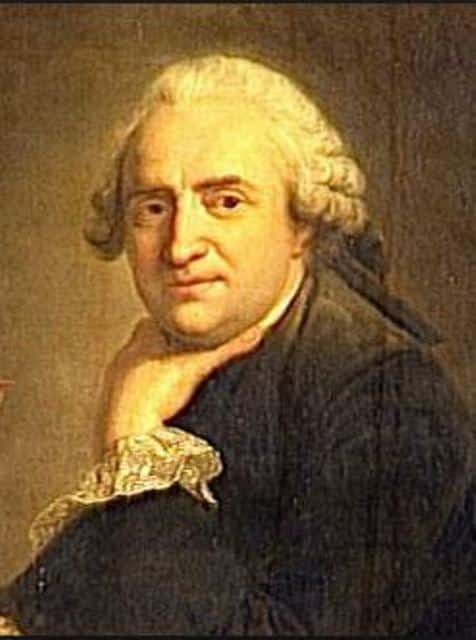

One night in 1667, in a frenzy, he stripped off his clothes and ran through streets of Paris, setting fires. Dr. Jean-Baptitste Denis, physician to king Louis XIV, had been experimenting with transfusing blood from animals into humans. He had his “aha” moment: let’s try this on Mauroy.

He infused ½ cup of calf’s blood into the mentally besieged man. Why calf’s blood? He believed that since the calf was a calm animal, its blood would be calm. Infusing it into Mauroy should calm the wild man.

This belief was called “vitalism,” that the blood somehow carried the essence of the creature. A stag’s blood carried courage; a horse’s, strength. A calf, calm.

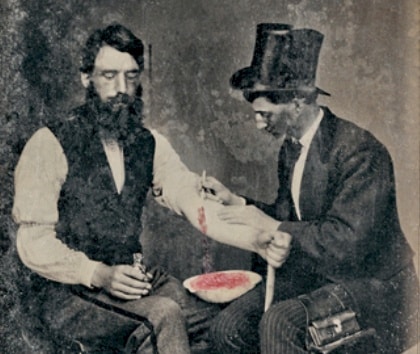

Prior to this experiment, other physicians had dabbled in transfusions with animals. Richard Lower, an English physician, tried transfusing blood from one dog to another: he figured out how to infused from an artery into a vein and it worked. His findings about the transfusion of blood are often ranked among the most important discoveries in medical history. And he is still remembered one of Oxford’s finest doctors. The English medical community worked on transfusions a year before Denis.

Dr. Denis had also tried transfusions in humans twice before, successfully.

So back to the madman. Unfortunately, Antoine Maury eventually died after the third infusion. Dr. Denis was accused of murder, and later acquitted, but it turned out that Maury’s wife poisoned Maury! He wasn’t the only wild one in that family. Human transfusions were stopped, and another 150 years would pass before they were attempted again.

And since it’s almost Halloween, I would add, unless you include vampires.