Laurie Kelley

May 30, 2011

Today is Memorial Day in the US, where we remember and honor those brave soldiers who fought in wars to protect our country and liberate others. It would be hard to find a family who does not have someone in it who gave their life for their country. I have at least one in my family: my uncle Jim Morrow, my father’s brother, who died in 1967 in Viet Nam. We find ways to remember our brave heroes: Jim has a place of honor on the Vietnam Wall in Washington DC, and on the virtual Wall, on line.

This week we will also remember heroes from a different war: HIV.

On June 2, PBS will at last broadcast Bad Blood: A Cautionary Tale, by Marilyn Ness. This emotional, deeply moving documentary portrays life with hemophilia before the “war,” when there was no blood clotting factor. This in itself can bring you to tears, watching children hobble about on crutches, suffering with joint bleeds, in hospital beds when they should be out in the sunshine playing. Then, the miracle of factor, and how it transformed lives from being crippled to being freed. Factor liberated all the children from this sad fate.

Who could have ever, in their wildest dreams, known that in the late 1970s a virus, unlike anything the world had ever seen, lurked in the nation’s blood supply? This is the stuff of science fiction, not reality. But it became our reality. Thousands were infected, and thousands died horrible deaths.

I know personally almost many of the heroes in the film: Dana Kuhn, Bob Massie, and Glenn Pierce. Bob says, this “is the story of a failed medical system, of companies and politicians putting profits before people, and of patients being kept in the dark about their very lives… It is the story of a critical piece of American history, when thousands of patients, doctors, and families came together to repair a broken system.”

Here is also Bob’s statement, which best expresses the heroism evident in those infected: “When I learned, more than twenty-five years ago, that my lifesaving injections had exposed me to a dangerous virus, I made the resolution to continue living each day, always staying true to myself and those I loved, and never giving up hope. I was lucky, and overcame them both with the help of world-class medical care and the love and support of my friends and family.” Bob is now running for US Senate.

But thousands of others were not so lucky. Like fallen soldiers in a devastating, insidious war, they are now remembered and honored in Bad Blood, which memorializes their struggle, their sacrifice and their legacy. Bad Blood is their local memorial park, their Viet Nam wall, their Iwo Jima monument. Clearly, their deaths, and the determined action of the survivors to seek justice and a change in the blood collection system and factor production, have made hemophilia treatments– and our entire blood banking syste–safer.

I cannot stress strongly enough to watch the movie. If you want to know the psyche of the US hemophilia community, understand its anguish and advocacy and determination, you must see this movie. If you want to see true American heroes, watch this movie. It’s not just a documentary, but a memorial to fallen soldiers.

Bad Blood is showing on WGBH at 10AM, 4PM, 6PM, and 11PM on June 2nd. Please forward and share this with your friends, family, community members, and anyone in the medical field.

Great Book I Just Read

Johnny Got His Gun

by Dalton Trumbo

You may have, like me, read this book in high school. It’s worth another read. Written in 1959, the novel was actually written in 1938 and published just after the start of World War II. This is the story of Joe Bonham, a youjng American WWI soldier who is horrifically disfigured and disabled. Told only from Joe’s thoughts and memories, Joe slowly becomes conscious and then must decipher what is happening to him. He realizes slowly he has lost all his limbs and his face; how does he cope with this horrific realization? All he has left is his skin and ears as sensory organs; he struggles to control his panicky mind.

Memories of home and family flood him; he reflects on why he went to war. Trumbo has a message, one that not all Americans in these times may want to hear. But we grow as humans when we read what we don’t always agree with; the horror of war, its terrible human cost. It can be viewed as a book about war and its effects (think of the thousands of scarred soldiers returning now; for second year in a row, the US military has lost more troops to suicide than to combat in Iraq and Afghan) or simply about the strength of the human spirit and surviving unimaginable loss in any field, at any time. This book is worth a read, though there are problems with run on sentences, grammar, etc. Two stars.

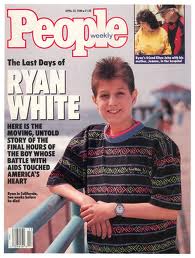

Ryan eventually found a school that welcomed him in Cicero, Indiana: Hamilton Heights High School. He thrived there.

Ryan eventually found a school that welcomed him in Cicero, Indiana: Hamilton Heights High School. He thrived there.