A Transformational Leader Remembered

We lost a few of people in our bleeding disorder community over the holidays, including young people with hemophilia. But in two weeks we lost two outstanding leaders in their fields. One was Val D. Bias, who I wrote about last week. The other was Dr. Tahir Shamsi of Pakistan. Both were my friends.

Tahir was a special sort of friend to me. We inhabited very different worlds: I am a woman, Christian, nonmedical, American. He is a man, Muslim, nationally-recognized physician and researcher, Pakistani. We were united not only by hemophilia, but by our burning desire to alleviate suffering.

We met on a boat in Rotterdam, in 1998. I was just beginning my work overseas, funded at that time by Bayer Corporation. Bayer had sponsored this cruise around the harbor, on a Tuesday evening during the World Federation Congress. As I walked about the ship, I saw him and he saw me. He is friendly, but intense. Efficient, wastes no time. Who was I and what was I doing there?

I explained about my program to identify patient leaders in developing countries, and teach them about leadership, not just management; about advocacy, not just meetings. About vision, mission, goal setting.

He invited me on the spot to come to Pakistan.

That startled me. Me? Mother of three young children, in Pakistan? Pakistan at the time was pretty isolated from the world. Almost no one went there unless they were diplomats. It seemed so… so foreign. And yet I was intrigued. I love challenges and love risks. How would the Pakistanis accept me? What could I possible do for them?

He assured me all would be well. I could stay with him and his wife, and family. He would arrange my visits while there.

A year later, I went. It’s a story for another time (maybe another book) but I fell in love with Pakistan. Never have I been so welcome in a country and made to feel at home. And that seems odd, given our “differences.” I learned the differences are mostly superficial. We have so much more in common than different. I returned three more times and would have gone in this past year, were it not for Covid.

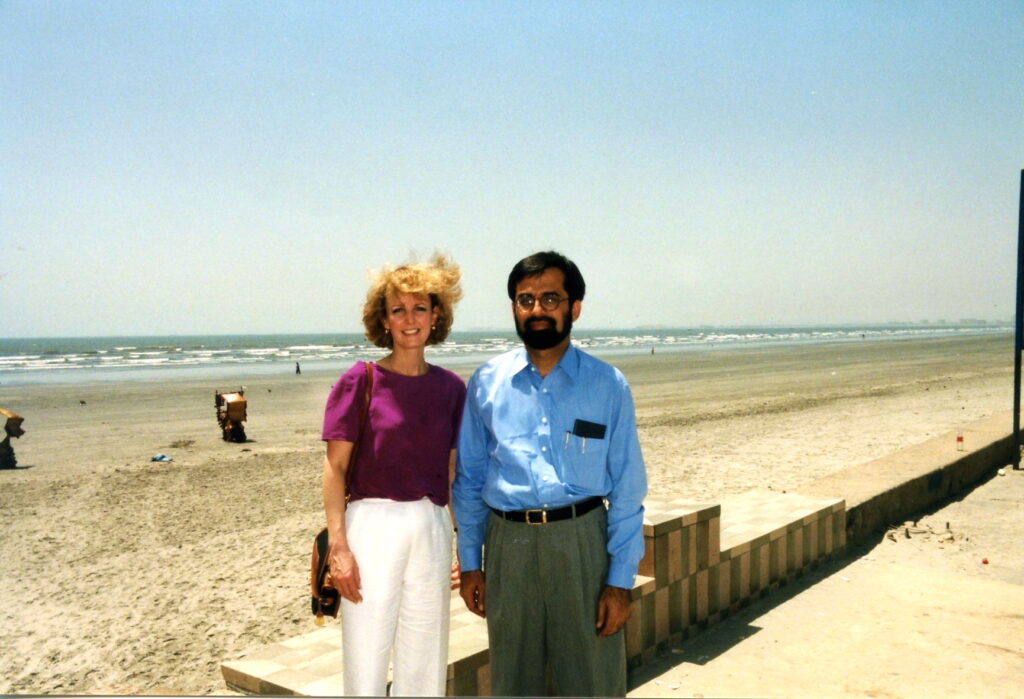

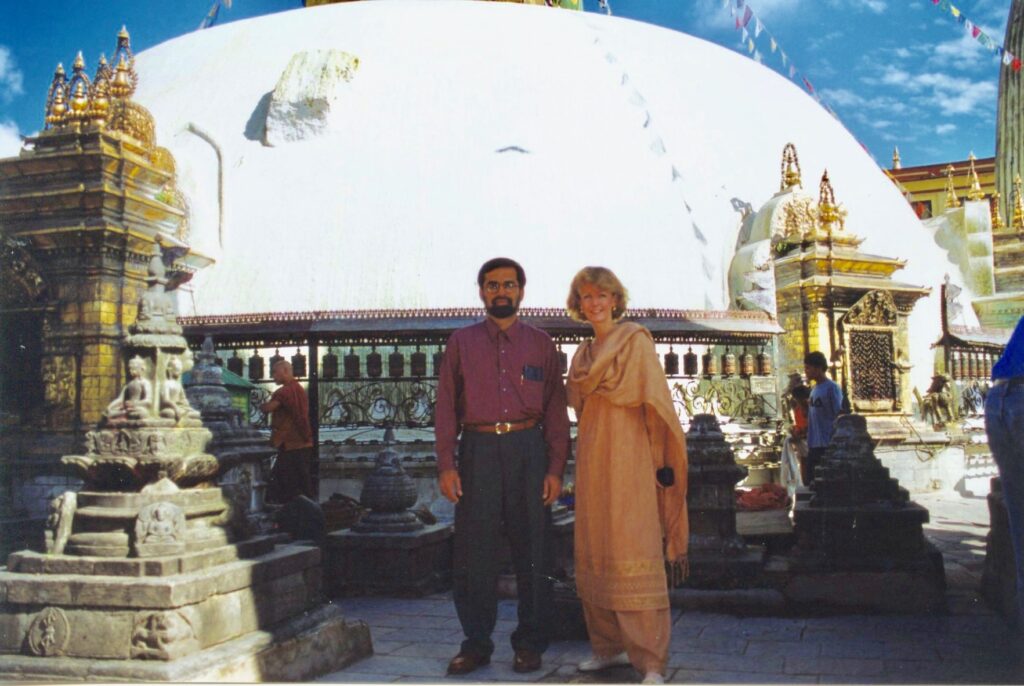

Tahir and I maintained contact throughout the years; I watched his family grow from two young children to five. I played with his children at their house, rode camels and ponies on the Arabian sea with them, took selfies, went to the mall, and had a ball. And Tahir and I met patients throughout Pakistan, worked with the new hemophilia society to help it grow, and we supported his surgeries with donated factor. We traveled to Nepal together, met up in Paris at a conference, and always had ideas brewing.

In fact, it was in Nepal, after our huge conference we gave for medical personnel, that Tahir shared his vision for a new institute in Pakistan. Somehow, we ended up sitting on the floor of a coffee shop, with him sketching out (on a napkin!) an idea for a new blood institute that would handle all sorts of cases, disorders, diseases of the blood, and be a research and training facility.

1999 Laurie and Tahir on Arabian Sea

First Visit to Pakistan

1999 Nepal Tahir and Laurie at temple

2000 Nepal Tahir Shamsi speaking

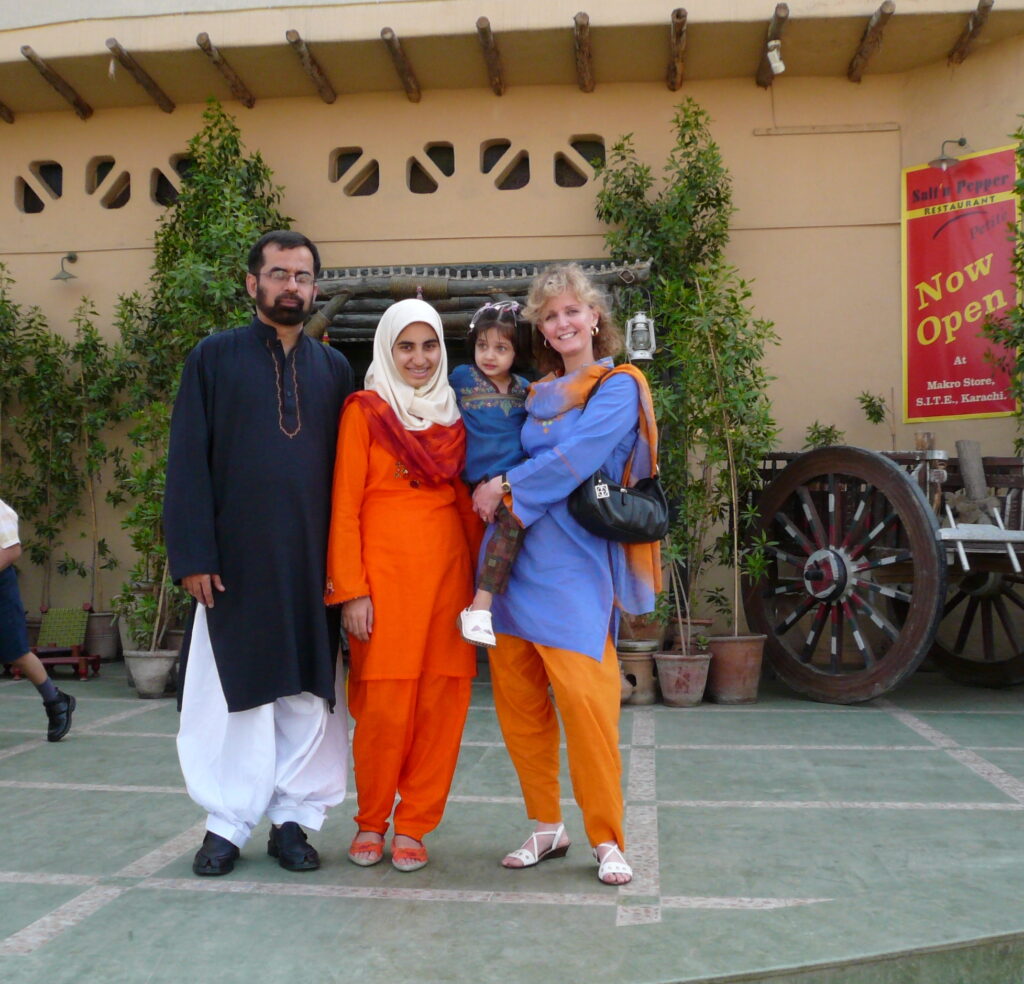

2007 Laurie, Tahir, Tuba, and Zohar

2007 Tahir with two of his beloved daughters

2007 Tahir & Mahnoor

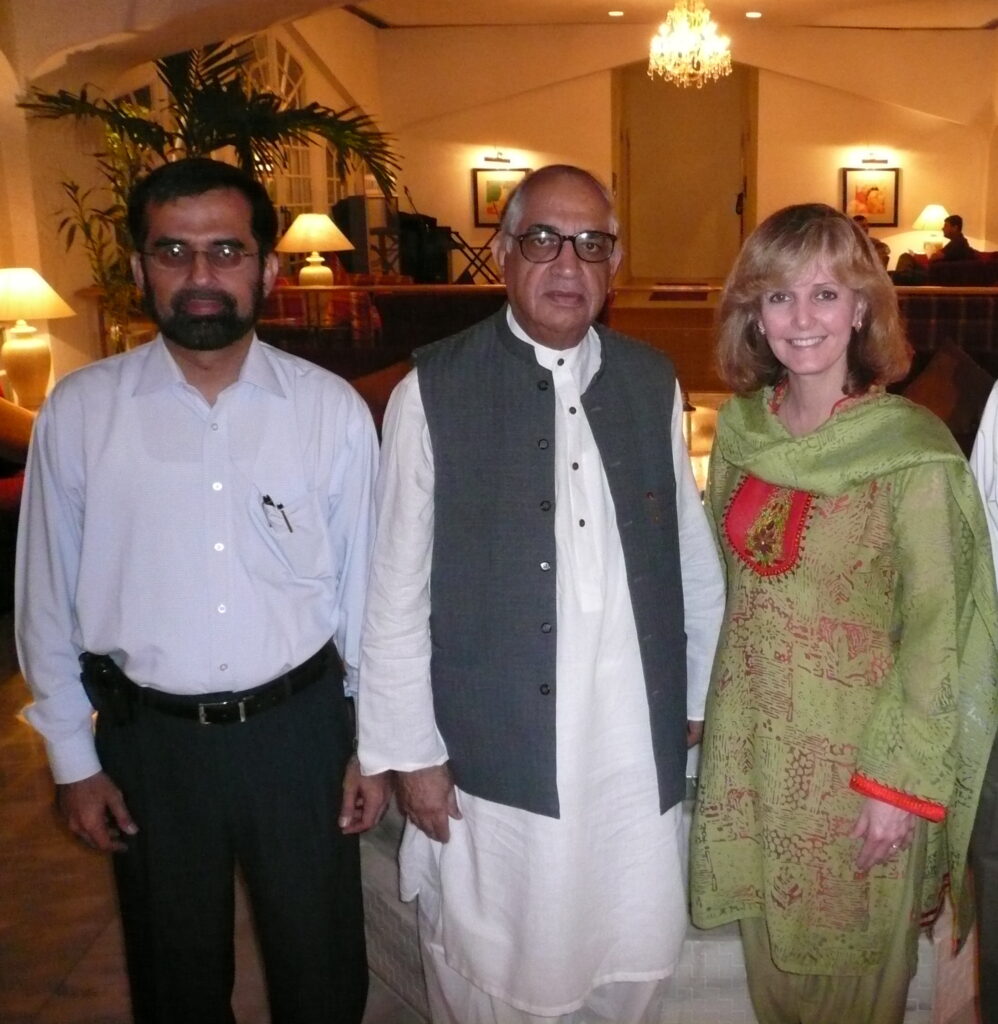

Tahir, Minister of Health Ahmed, Laurie – 2007

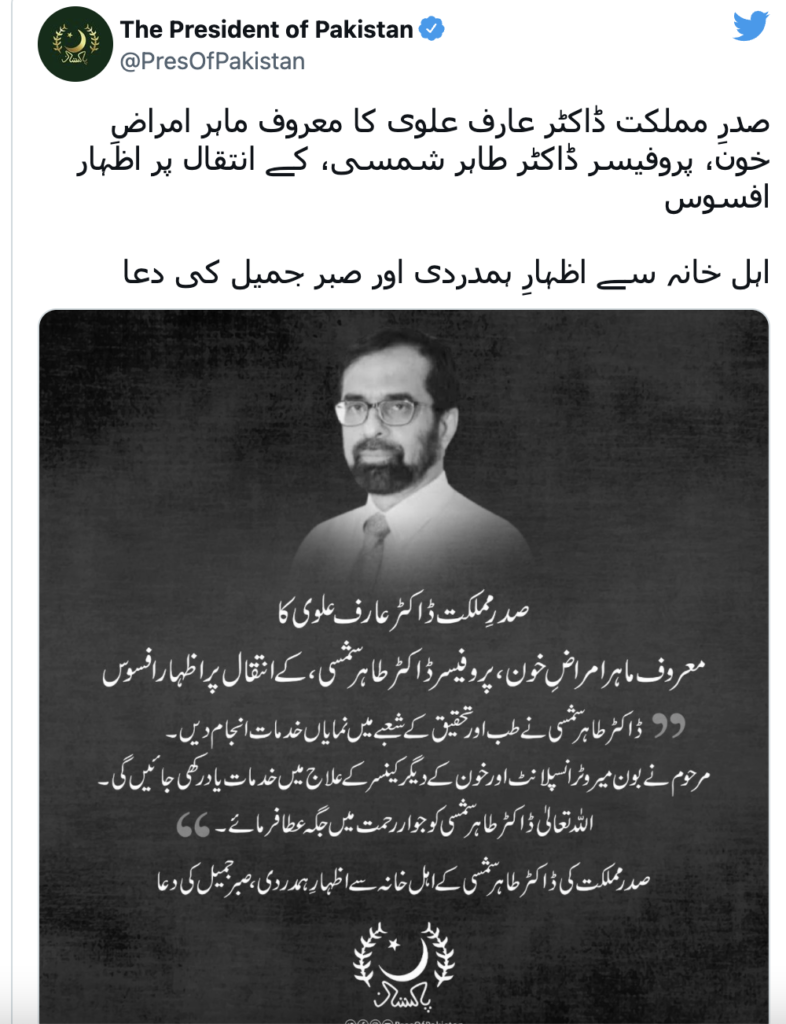

It all came to pass. The National Institute for Blood Diseases was created and Tahir founded Pakistan’s first bone marrow transplant program. The president of Pakistan recognized him for his incredible achievements. And the president offered his condolences in a tweet shortly after Tahir’s passing.

He got up to go to work in December, as usual. We had just messaged one another about how I would come over as soon as it was safe to travel, and stay at his new home, which accommodated all his growing family. He messaged, “You are always welcome.” Combination work and social visit. The kids are mostly grown, though the youngest is still just 15. I imagine he kissed them good-bye, as he adored his family, and had his driver take him to the office. We would have had interns to meet with, surgeries and patient visits planned. I do know he felt ill suddenly, and asked to be driven to the hospital. He suffered a massive brain hemorrhage, of all things. He never recovered and died, age 60, with so many depending on him, with so many achievements, but I know with so many more things he wanted to accomplish.

I don’t ever recall him saying he had a vacation in the 23 years that I knew him.

His death shocked me. You can never believe so wonderful a healer could be so ill. I could and would just pick up my phone whenever, and could message this famous and highly regarded physician, and chat with him like you would a regular person and friend.

But no more. Never again. He was gone, in a flash, a heartbeat, as if he sped away to attend to a medical emergency and never returned. He was always helping others.

The grief over his passing was palpable and deep. The NIBD team wrote on Facebook: “He was a national asset, a mentor to the juniors, a patron for many noble causes and a fatherly figure to all. Our loss cannot be described in words as the void he leaves behind is unfillable. He was director of the stem cell program, paragon of health research, an outstanding individual with excellent mentorship abilities, and an incredible human being. May Allah grant him the highest place in Jannah. Ameen.”

I will return to Pakistan, but it will never be the same without my friend, this incredible pioneer of medicine. He was a transformational leader, of the rarest type.

I

I