Alternative Pain Relief

Pain is highly personal. No two people experience the same feeling of pain, even when it’s the same injury, like a muscle bleed, or experience, like childbirth. A joint bleed may feel tingling to one, stabbing to another, or throbbing to someone else. A man with hemophilia A said, “Pain is pretty deeply personal. I personally have never been able to figure out what to say when a nurse asks me to describe my pain.”

But it’s especially personal when trying to describe the level of pain. Doctors often ask patients to rate their pain on a scale of 1 to 10. But what is a 1? What is a 10? A level 8 to one person might be a level 3 to another. Ed, who has hemophilia A, notes, “The HTC [hemophilia treatment center] will understand that most of us older guys have a base pain level that stays steady at a 5 or 6 every day. We’ve gotten used to that level of pain and this is our ‘normal.’ What’s difficult is when you go to an ER and try to relay that same information.” This is critical when people with bleeding disorders try to explain their level of pain to their doctor. Not appreciating or understanding how much pain a person is feeling may lead to an inefficient treatment for that pain.

Bonnie interprets her pain at lower levels when compared to people without a bleeding disorder. “I feel like what would be painful to someone else is just the norm for me. And I don’t find it painful because I’ve learned to live with it.”

Because pain is so personal, medication may not be the first—or the only—option for chronic pain. Instead, both patient and physician can consider different types of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) to learn how to handle chronic pain. And like pain, CAM can be highly personalized as well.

What Is CAM?

CAM is any adjunct (additional) therapy, like massage, used along with conventional medicine. It’s an important part of a multimodal or multidisciplinary approach to pain management. It’s also important in integrative medicine, which focuses on the whole person and makes use of all appropriate therapeutic approaches, healthcare professionals, and disciplines to achieve optimal health and healing. Here are some of the most common CAM therapies:

Relaxation Therapies. Relaxation teaches you to relieve tense muscles, reduce anxiety, and alter your mental state. Mindfulness meditation helps you focus attention on a specific object or your breathing patterns to induce relaxation. Guided imagery is a conscious meditation technique of relaxation followed by visualization of a soothing mental image, like walking on a beach at sunset.

Biofeedback Training. You can learn how to recognize and change your biological reactions to stress and pain by using electronic equipment to monitor your physical responses: brain activity, blood pressure, muscle tension, and heart rate.

Behavior Modification. Some people with severe chronic pain may become anxious, depressed, homebound, dependent, or bedridden. Behavior modification helps you create a step-by-step approach to confronting challenges by changing your behavior and shifting your attitude. Matt Barkdull, a man with hemophilia B who is also a licensed mental health specialist, says, “Behavior modification and stress management are my go-to interventions. I resist the urge to curse my bad luck, attack my self-identity, or become bitter (for that which we harbor is that which we attract). I believe pain is there to teach me a lesson, to remind me to appreciate better days ahead. When I meditate upon these things, I become more grateful for the important things in my life, and make better decisions. These interventions seem to work best when pain is dull but constant and for bleeds that are relatively minor but have caused some mobility problems that will require a little time to heal. Spiking and blinding pain (deep muscle bleeds from injury) often requires me to reach out and share my struggles, perhaps take a pain pill or two, and seek some relief. It’s hard to be mindful while battling the sting of acute pain. However, I find if I deliberately engage in deep-breathing exercises and stay connected while avoiding allowing my mind to wander and unhinging from false perceptions, the pain is much better controlled.”

Stress Management Training. If your pain level is high, your stress levels probably are, too. This training helps you maintain a routine schedule for activity, rest, and medication. It incorporates exercise or physical therapy into your daily routine, and trains you to keep a positive outlook.

Hypnotherapy. Therapeutic or medical hypnosis directs your focus inward to help you relax and reduce pain and anxiety. You can learn self-hypnosis from a trained hypnotherapist.

Counseling. Individual, family, or group counseling with a professional trained in pain management can provide emotional support and guidance. Tina, mother of two young children with hemophilia A, notes that anxiety is a type of pain: “Most of my boys’ pain is anxiety-related. It causes discomfort. I feel my children are more anxious than non-hemophilic kids because they associate injury with the added step of factor.” George adds, “Speaking with a mental health professional and learning meditation helped me the most. I can’t tell you how at peace I became when my mind accepted the fact that pain is part of my life and I can turn it into power and motivation to help others.”

Acupuncture. Many patients report pain relief from this ancient Chinese technique of inserting and manipulating thin needles into specific points on the body known to control pain pathways.

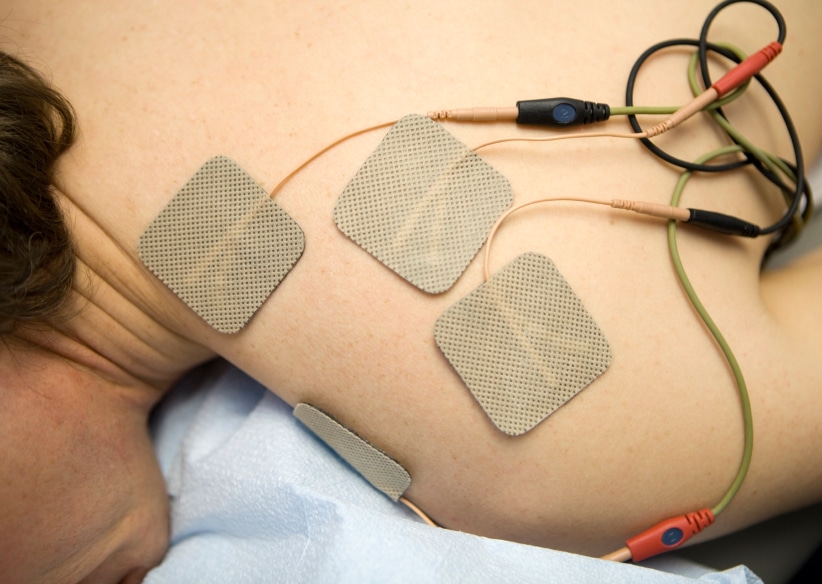

Dozens of other therapies, including acupressure, massage, and chiropractic manipulation, may help control pain. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulators (TENS) deliver electrical impulses to interfere with pain transmission. Ultrasound therapy warms joints internally to provide pain relief, and laser treatments may provide relief in a similar way.

A good management plan for chronic pain must be personalized. It should use a multimodal approach, which addresses the psychological component of chronic pain by treating depression and reducing anxiety and stress. A multimodal approach includes adjuvant therapies (antidepressants and anticonvulsants); an exercise and/or physical therapy component; and some form of CAM, which allows the person to manage moderate to severe chronic pain with the lowest possible dose of painkillers.

Here’s how Max, a person with hemophilia A, sums up personalized pain: “I’ve had to learn to understand my pain in ways that were perhaps discouraged at an earlier age. Pain is a friend; it’s part of me. I’m learning from it every day and learning to live with it makes it less of a burden.”

Acupuncture is safe for people on prophylaxis. If you’re considering acupuncture, first talk to your hematologist or the staff at your HTC.