Ride to Remember 2014: Honoring the Fallen

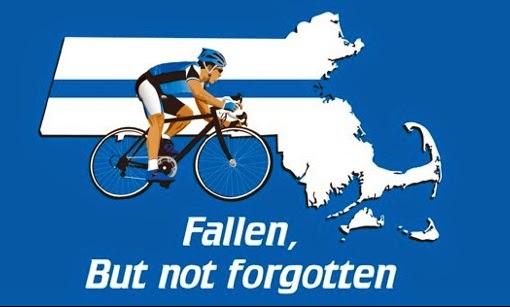

Hope for the human race was abundant Saturday morning downtown in Springfield, Massachusetts, where 240 cyclists of all ages, races, genders and professions lined up to cycle 106.7 miles to the State House in Boston. This was the second annual “Ride to Remember,” to honor fallen police officers and to raise money for their families. “Fallen but not Forgotten” was the slogan, printed on the back of the 240 riders’ uniform shirts, colored police-blue.

Hope for the human race was abundant Saturday morning downtown in Springfield, Massachusetts, where 240 cyclists of all ages, races, genders and professions lined up to cycle 106.7 miles to the State House in Boston. This was the second annual “Ride to Remember,” to honor fallen police officers and to raise money for their families. “Fallen but not Forgotten” was the slogan, printed on the back of the 240 riders’ uniform shirts, colored police-blue.chilly and moist; the bikes being unloaded and tires pumped; the massive

American flag unfurled from two cranes in the semi-dark; the dawn just breaking

over what would be a perfect-weather day for an endurance ride; support buses queueing

up and repair vehicle positioned in place.

now a K-9 officer, his wife Lee, on her first “century” ride, and my boyfriend Doug, a marathoner and endurance athlete. The riders were police officers, fire fighters and family members from all over Massachusetts. 106.7 miles later we would be at the State House for a ceremony to honor the fallen.

After pumping our tires up and joining the bulging street of riders, I looked down and saw bad

After pumping our tires up and joining the bulging street of riders, I looked down and saw badnews—my front tire was flat! I jumped off, ran to the far back of the crowd where the vehicles were, Doug following, searching for the repair vehicle. Meanwhile the clock was ticking as the riders were clipping in, ready to. I finally found Steve, the repair guy, and in 30 seconds he had me ready to go. Clip-clopping on my cleats, juggling my bike, sprinting back to the riders… but they were gone.

had to slice right between a parallel line of police motorcycle escorts until we became the last of the riders in the group. It was cold; by mile 10 our hands were stiff, noses running. I found that I couldn’t shift to the big gear because my left hand simply wouldn’t obey—too cold!

Washington DC at the NHF event, and while I hit the gym once, I didn’t feel warmed up; the cold air wasn’t helping. After the first break in Palmer, MA, where the support staff served boxes of bananas, bagels, Clif bars and Gatorade, we fueled up (you must keep eating throughout the ride), stretched out and within 15 minutes were back on the road. We immediately hit a hill; there would be many tortuous hills on this long ride, which tested not only your aerobic capacity, but your quad strength, and your mental fortitude. Honestly, I kept hearing in my head, “I think I can, I think I can…” Tim and Lee were somewhere ahead of us; Doug stayed in the large gear (the hardest) the entire 106.7 miles, and powered up every hill. That. Is. Crazy.

or through them—ouch! Rusty barbed wire. One sliced my knee a little; I thankfully didn’t get a piercing where none was desired and I headed back. A little drama is good for the story and the medical crew was delighted to have something to do.

appears dark, when work becomes monotonous, when hope hardly seems worth

having, just mount a bicycle and go out for a spin down the road, without

thought on anything but the ride you are taking. ~ Sir Arthur Conan DoyleAuthor of Sherlock Holmes

Back on the road and the rest of the ride was wonderful. I hit a little “wall” at mile 40, just

Back on the road and the rest of the ride was wonderful. I hit a little “wall” at mile 40, justfeeling like I could easily nap, but oddly, by mile 60 I was revved up and

flying. We took hills doing 15 mph at times, and flew at 32 mph downhill. We

had a police escort the entire way, so were well protected from cars. All

traffic was stopped as our entourage sped through intersections, town centers,

crossed highways, thumped over railroad tracks. I took only one spill when, to

avoid crashing into another cyclist, I couldn’t complete a sharp left turn to

cross railroad tracks at a 90 degree angle. My tire went right into the track

groove and I gracefully slid to the ground. No harm done. Doug and Tim had a

crash—together! Other riders had several crashes and there were many chains

that fell off.

By 5:30 pm, we

By 5:30 pm, werode into Boston, past the famous Citgo sign, with crowds along the way

cheering us on. We swarmed together like bees as we pulled into the State House

and congratulated each other. I was so proud of Lee, who had only taken up cycling

this past spring. This goes to show what training and determination can do

(though she seems to have some natural talent). And Doug was outstanding, and

now hooked on cycling. We’re going to sign up for some classes this winter with

a pro to learn how to improve our performance.

and firefighters (my older brother Tom Morrow is also a firefighter!): what wonderful public servants and what better way to tell them, to show them, how proud we all are: spending out day on a physically grueling ride, with such positive feelings, surrounded by some of the most honorable people you’d ever want to know.

|

fallen, but never forgotten. I think of Barry Haarde and his remarkable Ride Across America, doing an average of 120 miles a day—a day! Think of it! For 30 straight days. It seems humanly impossible, until you realize that when you have a passion, a cause, an injustice to fix, and some training and a goal, almost nothing is impossible.