The Royal Disease and Russia

Both the Royals and the Russians have been making the news this past year, not much of it good. For the Royals, it’s mostly just the Markles (on their “Privacy Tour”). For Russia…. well, let’s not go there.

While Russia is making a ruinous name for itself these past two years, it’s famous for its hemophilia history. Which originated from the English Royals.

We noted last week that it’s Bleeding Disorder Awareness Month, and we shared some popular myths about hemophilia. One was that hemophilia has been dubbed “The Royal Disease.” I shared in detail how this happened, and who it affected in my blog here.

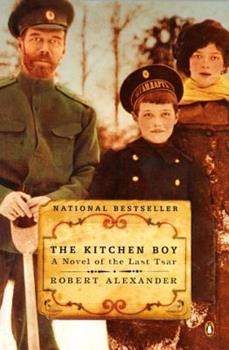

But the most famous outcome of a genetic link in the English Royal family happened when Princess Alix, whose grandmother was Queen Victoria, a carrier of hemophilia B, married Tsar Nicholas II of Russia. Queen Victoria had nine children, of whom two were carriers (Alice and Beatrice) and one had hemophilia (Leopold). It was well known that hemophilia was now running in the family.

Alix, nicknamed “Sunny” by Nicolas, gave birth to Alexis (or Alexei), after already having four girls. They got their heir to the throne. But Alexis had hemophilia.

Alexis had no access to clotting factor of course; this was 1904, after all. The royal family came rely on a person of ill repute: Rasputin, the mad monk. He had a lascivious reputation but also a track record of helping people in pain, probably through hypnosis. Rasputin became ingratiated into the royal family and helped also to bring down the Russian monarchy. It’s been proposed that Nicholas II was so distracted by his son’s suffering due to hemophilia, that eventually he lost his grip on the monarchy at a time when the Bolshevik Revolution was poised to strike. And it did. It has been proposed that hemophilia changed the course of World War I, and changed the course of history. The Cold War, the Soviet Empire… all find their roots in the royal palace of the Tsar and a little boy with hemophilia.

Order Alexis: the Prince Who Had Hemophilia here for your child with hemophilia.