“God has kept me alive…” to Serve

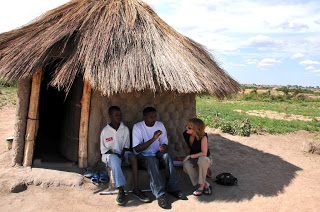

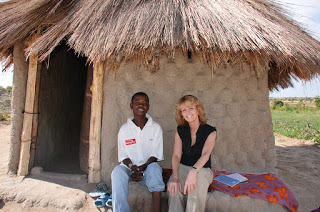

This essay was submitted by someone I have known since my first visit to Zimbabwe, in 2000. It is sad, and details a life of loss, and yet a life of hope. Please always keep in mind that in most developing countries, access to factor is almost impossible. If you think you have factor to donate, contact me, and I will help find a home for it. ~ Laurie, laurie@kelleycom.com

My name is Nqobizitha Ndlovu, which [is of Zulu origin] and means “Conqueror” in English. I’m 34 years old, living with hemophilia A since birth. I was born and live in Zimbabwe.

I was born into a family of four boys, of which I am the eldest. Growing up together with my siblings, life has not been rosy; it has been pain after pain, suffering because of hemophilia and life challenges as well. I am coming from a very poor family as my father used to do menial jobs to sustain us.

Zimbabwe’s economy is in shambles and the health system is in a very bad state. The government hospitals have no diagnostic or any other important machines, or they are not working, if there is any at a single hospital servicing the whole country. No painkillers; blood transfusion is very expensive and it cost more than $100 American dollars for a single pint of blood. Only private hospitals can offer such services as diagnostics at a very high cost. That is a life of hemophiliacs in Zimbabwe.

My young late brothers and I endured a lot of pain considering our condition. We have been friends of the hospital quiet often and countless times. We have been relying on donated factor VIII ever since, with the help of Laurie Kelley. It has been a struggle in our journey of life as my parents struggled very hard to cater for our needs.

My parents and we were sharing a single bedroom house. School was another challenge for us as we used to walk for almost four hours going and another four hours coming back. That contributed to bleeding easily. Regardless of that we were excelling at our studies.

In 1996 I lost one of my young brothers through tonsil bleeding; he was two years old and the third born. Mthokozisi was his name, which means “happiness” in English. After bleeding for three days from his tonsils, he unfortunately passed on.

The year 1998 was another bad one for me again. We had just knocked off from school. My young brother Khumbs and I, and other kids, were playing on our way home. Khumbs fell on his knee from high rocks. From there he couldn’t even move his leg as he had hit with a knee down. All the other kids left us there as I struggled to carry him on my back. We arrived home very late and Khumbs was in deep pain. He could not go to school anymore for at least two years. Khumbs’s knee developed an infection which resulted in his leg being amputated. Khumbs lost his leg like, just like that.

The year 2002 was another bad one for me again as I lost the person whom I had been relying on when I was not feeling well. My mom passed on as well. I was left broken and helpless at the same time.

In 2003 I was still digesting the pain of losing my mother, when my father passed on. It became sorrow on top of another sorrow. I was really affected psychologically, physically and socially, and it also affected my schoolwork at the same time. I lost concentration on my studies. My health dwindled badly.

In 2009 my younger brother Khumbs had an internal bleed which resulted in him passing on that year on November 9. Laurie Kelley had tried to source some factor VIII for him, which arrived in the evening. But he passed on in the morning. Now I had nowhere to go— no one to share my pain with as he was the closest to me.

In 2017 I was involved in a horrific incident where I lost one of my eyes. I was admitted for one and a half a months in the hospital and bled for 21 days nonstop. I almost lost my life, which became a miracle to be alive according to the doctors at Parirenyatwa, Zimbabwe’ s biggest hospital.

During the time at the hospital it was discovered that I had developed factor VIII inhibitors. Laurie Kelley has done a lot for us that I cannot count it all. I am now using the NovoSeven which I always get from Laurie Kelley.

Fast forward to January 2023. My one and only brother that I was left with also passed on through throat injuries and bleeding. He could not access factor VIII at the right time because he was in a remote area. That was the end of all my family members as I am now alone, with my son Brooklyn, a nonhemophiliac who is eight years old.

I was recently voted to be the Zimbabwe Haemophilia Association as vice president. It’s a nonprofit organization. I want to serve people with hemophilia in Zimbabwe and any other bleeding disorders with all my heart. I have seen it all and I believe the high God has kept me alive up to this far to do that. We are doing all possible ways to reach out to every corner, to save some souls out there.