Kilimanjaro: Fire and Ice

The true result of endeavor, whether on a mountain or in any other context, may be found rather in its lasting effects than in the few moments during which a summit is trampled by mountain boots. The real measure is the success or failure of the climber to triumph, not over a lifeless mountain, but over himself: the true value of the enterprise lies in the example to others of human motive and human conduct.” —Sir John Hunt, leader of the 1953 British expedition that first ascended Mount Everest

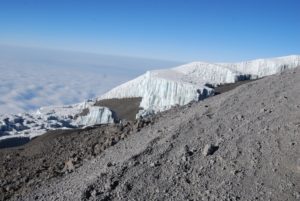

This was a week of triumph over self, as our group of nine attempted to summit Kilimanjaro, the largest free-standing mountain in the world and the rooftop of Africa. Kilimanjaro was born 300 million years ago in fire, when massive tectonic plates in Asia shifted, creating the Great Rift Valley and pushing up sections of the earth that eventually formed the volcano Kilimanjaro. If you climb Kili, like I did this past week, you will see miles of enormous lava rocks of black basalt littering the mountain, rocks that were birthed deep in the womb of planet Earth and blasted out when the volcano exploded. During the ice age, glaciers formed, adorning sections of Kili with massive frozen sculptures.

I thought of the similarities to hemophilia this week: bleeding into joints is the fire, the pain; ice, the pain reliever. And trying to improve hemophilia health care in developing countries? A grueling climb up a mountain is a good metaphor. For a successful climb you need self-discipline to get in shape, leadership, guides or a map, a compass, equipment, trust in your guide, and trust in your teammates.

Our team? An amazing group! Eric Hill, vice president and COO of Diplomat Specialty Infusion Group, and his 15-year-old son Andrew. Eric serves on our board of directors for Save One Life and sponsors 31 children. Eric climbed with me in 2011 with his son Alex. Rich Gaton, co-founder and president of BDI Pharma, a specialty distributor that provide hemophilia and other therapies. Rich’s company is a proud member of Save One Life’s Dedication Circle, sponsoring 20 beneficiaries over the past eight years. With Rich are his wife Wendy and two daughters, Taylor (20) and Samantha (16). Mike Adelman, vice president of commercial operations for Aptevo Therapeutics, Inc., manufacturers of the recombinant factor IX product Ixinity. And Jim Palmer, MD, a surgeon from Philadelphia and friend of Mike’s. Individually, we wished to triumph over self. Together, we climbed to raise over $65,000 for Save One Life.

Day 1: August 7, 2016 Sunday

We all gathered in the lobby of the Kibo Palace hotel in Arusha, Tanzania, excitement shocking us like static electricity each time we hugged one another good morning. Our guides, Hesbon, Kelvin, Victor and Edwin, helped us put our stuffed rucksacks on the bus. We clambered aboard and squeezed in among porters, guides and bags. It was a two-hour ride to the Machame Gate, where our adventure awaited.

First we stopped at the familiar store we stopped at five years ago, when Eric and I and another group summited Kili, to pick up snacks. We sat about in the sunshine on the grass, waiting for the guides to return. Hesbon went with me across the street to a shop to get a Nalgene bottle, for $7 which he fronted. I don’t think I ever even used the bottle in the end.

First we stopped at the familiar store we stopped at five years ago, when Eric and I and another group summited Kili, to pick up snacks. We sat about in the sunshine on the grass, waiting for the guides to return. Hesbon went with me across the street to a shop to get a Nalgene bottle, for $7 which he fronted. I don’t think I ever even used the bottle in the end.

Finally, back on the road. We passed roadside shops and rural homes, dust swirling from our speed. When we reached the Machame Gate (elevation 5,718 feet), we felt pretty calm. Outside the gate, a mob of vendors hawking shirts and hiking supplies. Inside, the gate was swarming with hikers, porters, bags. It would be a very late 12 pm before we started our official hike. In the meantime, Hesbon filled out paperwork while we put on gaiters and filled our Camelbacks with water. We would carry a 25-lb daypack each day while our porters would carry our 50-lb rucksack, along with their own daypack and all the accouterments of camping for nine: mess tent, folding chairs, port-a-potty, our tents and mats, and food for 29 porters, four guides, a cook and nine hikers for six days!

Our first day then had us hiking about six hours to the Machame Camp, elevation 9,927 feet. The route was a groomed trail for the most part, through a dense and moist rain forest. It was cool and progressively dark. The forest was lovely, lush green, with trees covered in soft moss, making them resemble a young deer’s antlers, covered in velvet. Many birds serenaded me. One had a distinct sound: “Tweet… bong!”

Our first day then had us hiking about six hours to the Machame Camp, elevation 9,927 feet. The route was a groomed trail for the most part, through a dense and moist rain forest. It was cool and progressively dark. The forest was lovely, lush green, with trees covered in soft moss, making them resemble a young deer’s antlers, covered in velvet. Many birds serenaded me. One had a distinct sound: “Tweet… bong!”

The hike was harder than the team expected and harder than I recalled from five years ago. Very steep, working our quads and calves intensely. At times we broke away from one another, then paired up with different teammates. Wendy took her time as she had asthma; husband Rich stayed by her side the entire day. The lead guide Hesbon also needed to stay with her as he always would be last to enter camp, to ensure his hikers were all present. Mike was stricken with food poisoning the night before. The hike was very difficult for him but incredibly he persisted and arrived at camp one. By 6 pm, the weather turned rainy and cold as we all stumbled at various times into camp. It was dark. Camp was crowded with people, so different than five years ago when there were perhaps three teams, spread out comfortably over the camp ground. Now there were maybe ten teams, with all their gear and porters and tents. Pandemonium in the dark, as we all shivered in the rain, waiting for our team to assemble and find one another! Our porters had our camp ready, and we finally found our tents and crawled inside.

I had a single tent; everyone else shared one. As I would each night, I laid out my sleeping bag, stuffing in my clothes for the next day to keep them warm when I awoke and placed necessary items for the night close by: Kleenex, water, cough drops. I was nursing a cold that would later strike my chest and make the hike difficult for me. One by one, we were being hit with physical challenges to the climb. Dinner was welcome, though we had to grope our way in the dark to the mess tent, careful not to trip on the tent stakes. Juju, a young man who doubled as a porter, would serve us each night. Each dinner usually started with steaming soup, rolls, followed by a main course– chicken, rice, beans, for example. Our team sat about the table, eating, joking and comparing experiences of the day. By 9 pm we went back to our tents, and crawled into our sleeping bags.

Day 2: August 8, 2016 Monday

I awoke at 4 am to the sounds of the porters preparing for the long day ahead. I had a pretty good night’s sleep though. My sleeping bag, rated for 0°, is toasty warm, making it hard to leave each morning as the temperature dropped more and more the higher we went. Each day started the same: Juju and Able brought us each tea or coffee first thing, to warm us up in our tent. This was a luxury, tea in “bed”! Then, they brought a plastic bowl filled with very hot water, to wash and brush our teeth in. You cannot imagine how important one little bowl of water becomes. Kilimanjaro is very dusty, and even by day two we were coated in dust. Washing was a luxury, and that little bowl of water became something I was excited to see each morning.

Then breakfast: usually a round of fried eggs, toast, jam, more tea or coffee, pancakes. Yes, they prepare all that fresh for us each morning! We top off the Camelbacks with water, toss in electrolyte pills, stuff in our rain gear (you can’t go anywhere on KIli with rain gear) and anything else needed for the day, pack our sleeping bags and clothes in the rucksack, and get ready to leave.

“Twende!” shouts the guide Kelvin, a big guy, at least 6 feet tall, who walks with a noticeable limp. Let’s go! We had our concerns about his limp, but also learn he was a national soccer player in his time. The leg injury forced him to retire, and he was able to still climb well, despite it. Mike is still not well, Wendy was much improved overnight, and the Gaton girls each have slight headaches, from the altitude. We are all taking Diamox, a hypertension drug that doubles as an altitude-sickness pill, but symptoms still appear in each of us from time to time.

Today’s climb was through a completely different geological zone, the Moorlands. Gone were the towering green trees and milder temperatures of the rain forest. Starting our hike with a bang, we immediately ascend a rocky path that leaves us gasping. The entire day would be spent climbing on rocks and not a trail, much like my Mt. Washington training hikes. The air was cold, and we were encased in cloud cover all day. We would miss some stunning views of nearby volcanoes, as we could see little but the path ahead. As we ascended, we put some space in between us on the hillside; through the mist, seeing other climbing parties in their various colored rain gear, I thought we looked like brightly colored beads strung on a necklace draped on the grey neck of some ancient beast.

We passed the hardier vegetation in this cold climate: the Everlast plant with its pretty flowers, and the “antifreeze” plant, which closes each night to protect itself from the cold. The topography has changed radically.

We climbed from 8 am until 2 pm, reaching Shira Cave Camp, at 12,355 feet. By now everyone was feeling good, except Mike. But he never complained, and still kept plowing forward on this difficult hike. At 4 pm, Edwin, a cheerful 28-year-old guide, asked us if we wanted to do a 45-minute acclimatizing climb while dinner was prepared. Despite the large number of climbing parties, there was more space at this camp, and we spread out. Eric, Rich, Mike and I all did the acclimatization climb, which was not hard. I felt great at this altitude and relished the climb on the rocks, which were beautiful.

We climbed from 8 am until 2 pm, reaching Shira Cave Camp, at 12,355 feet. By now everyone was feeling good, except Mike. But he never complained, and still kept plowing forward on this difficult hike. At 4 pm, Edwin, a cheerful 28-year-old guide, asked us if we wanted to do a 45-minute acclimatizing climb while dinner was prepared. Despite the large number of climbing parties, there was more space at this camp, and we spread out. Eric, Rich, Mike and I all did the acclimatization climb, which was not hard. I felt great at this altitude and relished the climb on the rocks, which were beautiful.

Later in my tent, I wrote a bit about the day and felt the cold seeping in. Tomorrow will probably be freezing temperatures when we awake!

with Eric!

Day 3: August 9, 2016 Tuesday

I wondered when I woke up, why am I doing this? Sleeping in a bag on the ground, freezing cold, facing a long hike ahead. I could be home, clean and warm, having summer fun! That was the one and only time I thought this during the six days, caving in for a moment to a human desire to escape misery. Instead, I switched to thinking what fun this was, to challenge oneself, to share hardship with fellow teammates, to see who and what we all are deep inside. I dressed careful within my sleeping bag, then braced for the cold. Frost etched all the tents as we emerged like lethargic bears awakening from hibernation. The sky had cleared! Now we could see other volcanoes, including the summit cone of Kilimanjaro, Kibo Peak. That was our goal! Everyone was excited. Our goal! Kibo Summit on Kilimanjaro Still smiling!

By now I was coughing with a chest cold, complicated by all the dust and increasing cold air. Everyone else was well but coughing too. This would continue for days even after our climb. Breakfast was high energy and we could feel anxiety; we wanted to get going. Breakfast was hot but soupy porridge, toast and tea, and fried eggs. By 7:30 am we were on the trail, looking forward to a four hour hike through the Barranco Valley. This was a totally different kind of hike today, mostly flat with a few hills to navigate. Victor, our guide, took my camera and snapped dozens of photo of us as we climbed. We had on warm outerwear now, as the wind picked up. By noon we were at the Lava Tower, a massive rock formation jutting out of the ground, looking a lot like a mini version of Devil’s Tower in Wyoming. Perfect spot for lunch and we all joyfully sat at the table. By now our team had gelled beautifully with each person playing a role. Mike was our jokester, keeping everyone laughing with his witty remarks. Samantha was our musician, and she and Mike began thinking of songs we could sing to use pole pole, which means slow, slow in Swahili. It was hysterical listening to the many songs of the 60s and 70s that accommodated this but my favorite was set to Mony Mony.

After lunch we checked gear, loaded up our stuff, and headed out for one of my favorite parts of the climb: the descent into the Barranco Valley. Our plan was to ascend all morning, to 15,000 feet, which we did at Lava Tower, then descend and sleep at a lower elevation, so we can acclimatize better. Barranco Camp, our goal, was at 13,066 feet. Passing through a natural gate of volcanic rock, we descended into the valley carefully. The topography changed again, with rocks surrounding us on the hills, and strange trees appearing, designed to withstand the wind and cold. These giant senecios are actually cousins to the daisies! And they looked like truffula trees, whimsical creations of Dr. Seuss, which was appropriate as each black boulder we passed was coated with moss, that appeared as little yellow fu manchus. It looked comically like hundreds of black-faced Loraxes were watching us pass through the truffula tree forest!

As beautiful as the descent was into the valley, the cold was seeping into our bones. Even Rich Gaton, who is so stoic and strong, confided he was freezing. My chest cold was painful and persistent now, and my nose was running chronically. When we arrived at camp, dotted about with colorful nylon tents, the weather was foggy, dreary, and cold—so cold. How would we do the summit if this bothered us? Andrew and I were shaking in our rain gear while heading for dinner at the mess tent. Our tents for sleeping that night were close together, so much that when Wendy or Rich so much as rolled over, I would know it! I felt badly as my coughing was going to bother my teammates. Wendy always seemed to have the right medicine for the right moment. She was our warm nurturer on the trip, despite struggling with asthma in the cold air this entire time.

Day 4: August 10, 2016 Wednesday

Summit Night!

We must embrace pain and burn it as fuel for our journey.—Miyazawa Kenji

Today we would climb to 15,239 feet to Barafu Camp, the final camp before the summit assault. First we faced a 7-hour hike, including scaling an 800-foot rock wall right after breakfast, then a long hike to camp, braving cold but more detrimentally, dust. We were excited, though! We started our day with the usual hot tea in the tent, followed by my priceless little blue plastic bowl of hot water. By now we have given up any semblance of being clean. Dust is everywhere. Breakfast is a time to share, be social, joke, check in with one another. Everyone was doing well, with an occasional high-altitude headache that faded after ibuprofen doses.

We geared up, and began the climb. Again, one of my favorite parts of the trip! My quads are feeling fantastic after all the training I did this summer, hiking Mt. Washington and working with my trainer, Dan French. In fact, I would not use my trekking poles on the entire journey, except for the rapid descent after the summit. So here, I vaulted straight up the wall using my quads and balance. Everyone did well; everyone scaled it and enjoyed photos at the top, where a crystal blue sky greeted us. The view—spectacular. We could see down into the valley. Our camp was now just a colorful speck. Our team was smiling and happy!

We geared up, and began the climb. Again, one of my favorite parts of the trip! My quads are feeling fantastic after all the training I did this summer, hiking Mt. Washington and working with my trainer, Dan French. In fact, I would not use my trekking poles on the entire journey, except for the rapid descent after the summit. So here, I vaulted straight up the wall using my quads and balance. Everyone did well; everyone scaled it and enjoyed photos at the top, where a crystal blue sky greeted us. The view—spectacular. We could see down into the valley. Our camp was now just a colorful speck. Our team was smiling and happy!

Onward with no time to lose. We marched down the valley, on slippery, dusty trails that plummeted down at 45° angles at times, maybe even steeper. Our guides held our hands and prevented falls whenever possible. At the bottom, we crossed creeks, jumped rocks, and made it to a flatter surface, dusty with volcanic ash powder, and dotted only occasionally by the oddly placed massive boulder. It was a surreal, primitive, prehistoric landscape. Grey and black base, domed by a brilliant blue ceiling. We were feeling the effects of altitude, which slowed us a bit. Eventually we started to ascend again, up the trails, where flat slabs of shale chimed when we stepped on them, adding a touch of class to the barren landscape.

Onward with no time to lose. We marched down the valley, on slippery, dusty trails that plummeted down at 45° angles at times, maybe even steeper. Our guides held our hands and prevented falls whenever possible. At the bottom, we crossed creeks, jumped rocks, and made it to a flatter surface, dusty with volcanic ash powder, and dotted only occasionally by the oddly placed massive boulder. It was a surreal, primitive, prehistoric landscape. Grey and black base, domed by a brilliant blue ceiling. We were feeling the effects of altitude, which slowed us a bit. Eventually we started to ascend again, up the trails, where flat slabs of shale chimed when we stepped on them, adding a touch of class to the barren landscape.

By the time we reached base camp, we were struggling with oxygen, sunburned and elated! This was it. What we came for. What we prepared all year for. The Moment! The entire camp was perched on a mountainside, and before us was the stunning, magnificent Kibo Peak, beckoning us to climb. We could clearly see its white glazed top, its rocky sides. Kili is a beauty of a mountain. I felt awed and honored to be standing before it. I made my way to my tent, ditched my backpack and gear and wandered about till all of our team made it to the camp. My coughing had gotten worse and my voice was hoarse and raspy. Hesbon offered antibiotics as a precaution. My lungs are my Achilles Heel, so I took them. They immediately gave me severe heartburn, so badly I was not able to eat much lunch. This was a bad sign as I would need my energy to summit.

By the time we reached base camp, we were struggling with oxygen, sunburned and elated! This was it. What we came for. What we prepared all year for. The Moment! The entire camp was perched on a mountainside, and before us was the stunning, magnificent Kibo Peak, beckoning us to climb. We could clearly see its white glazed top, its rocky sides. Kili is a beauty of a mountain. I felt awed and honored to be standing before it. I made my way to my tent, ditched my backpack and gear and wandered about till all of our team made it to the camp. My coughing had gotten worse and my voice was hoarse and raspy. Hesbon offered antibiotics as a precaution. My lungs are my Achilles Heel, so I took them. They immediately gave me severe heartburn, so badly I was not able to eat much lunch. This was a bad sign as I would need my energy to summit.

But attitude and motivation go a long way, and I was pumped up! Our plan, explained Hesbon to the group, was to have a light dinner, then return to our sleeping bags to catch maybe a few hours of sleep. Then we would depart in two groups: the first was Eric Hill and son Andrew, who proved to be the mountaineers of the group. They could go faster than us and wanted to not have to stop for breaks (stopping for frequent breaks can refuel the climbers but can also allow the cold to settle in, and can actually demoralize the faster climbers who crave to keep moving). Their guide would be Kelvin, and they’d leave at 1 am Thursday morning. Our group was the second group, guided by Victor, including everyone else. We’d leave at midnight. Wendy opted not to summit, which was disappointing to all, but the right decision. She had struggled with asthma and dust the entire day, and it was quite frankly astonishing she was even at base camp. As sweet as she is, the woman has a core of steel!

But attitude and motivation go a long way, and I was pumped up! Our plan, explained Hesbon to the group, was to have a light dinner, then return to our sleeping bags to catch maybe a few hours of sleep. Then we would depart in two groups: the first was Eric Hill and son Andrew, who proved to be the mountaineers of the group. They could go faster than us and wanted to not have to stop for breaks (stopping for frequent breaks can refuel the climbers but can also allow the cold to settle in, and can actually demoralize the faster climbers who crave to keep moving). Their guide would be Kelvin, and they’d leave at 1 am Thursday morning. Our group was the second group, guided by Victor, including everyone else. We’d leave at midnight. Wendy opted not to summit, which was disappointing to all, but the right decision. She had struggled with asthma and dust the entire day, and it was quite frankly astonishing she was even at base camp. As sweet as she is, the woman has a core of steel!

I actually was able to get some sleep, though had to pass on dinner, as my stomach burned with the aftereffects of the antibiotics. At 10 pm, I awoke and started planning what to wear to the summit: layers. Incredibly, the weather was mild, at only 20°, with almost no wind. This was a stark contrast to five years ago when it was -5° with 50 mph gusts, freezing us, sapping us of strength, and cloaking any view with white out conditions. We couldn’t get off Kibo fast enough then. This time would be radically different.

I actually was able to get some sleep, though had to pass on dinner, as my stomach burned with the aftereffects of the antibiotics. At 10 pm, I awoke and started planning what to wear to the summit: layers. Incredibly, the weather was mild, at only 20°, with almost no wind. This was a stark contrast to five years ago when it was -5° with 50 mph gusts, freezing us, sapping us of strength, and cloaking any view with white out conditions. We couldn’t get off Kibo fast enough then. This time would be radically different.

We gathered in the mess tent and did a gear check. We were each assigned someone to carry our backpack and monitor us. Team Kilimanjaro does a great job of motivating climbers as well as monitoring their physical condition for signs or mountain sickness. Off we went!

We gathered in the mess tent and did a gear check. We were each assigned someone to carry our backpack and monitor us. Team Kilimanjaro does a great job of motivating climbers as well as monitoring their physical condition for signs or mountain sickness. Off we went!

The guides forced us to go pole pole. One step, then another, as slow as possible. They also created a rhythm, so important in keeping your pace and momentum. The night was clear and millions of stars burned overhead. It was a night created for a perfect summit! Step, swing, step, swing went our gait. Up, up the rocky path to the summit. I monitored the time and by 1:30 am we had our first break. Hydrating is key, though water tends to freeze in the Camelback tube. I looked upwards at the infinite sky and saw constellations: Orion the Hunter, Taurus, and then Cassiopeia, shaped like a W. The W was upside down, forming an M (for mountain?) over Kibo, and it guided me through the night. Twice I saw shooting stars, like fireworks celebrating our summit. I took the time to take out my iPod and started playing music to keep me going. Five years ago I lost track entirely of the night, and 7 hours merged into memories of only about an hour. Not this time: I played about three hours of Metallica and the Doors, and then Guns N’ Roses. At 5 am, I was actually dancing with the porters on the mountain, gyrating as they sang, then playing air guitar to Welcome to the Jungle….

The guides forced us to go pole pole. One step, then another, as slow as possible. They also created a rhythm, so important in keeping your pace and momentum. The night was clear and millions of stars burned overhead. It was a night created for a perfect summit! Step, swing, step, swing went our gait. Up, up the rocky path to the summit. I monitored the time and by 1:30 am we had our first break. Hydrating is key, though water tends to freeze in the Camelback tube. I looked upwards at the infinite sky and saw constellations: Orion the Hunter, Taurus, and then Cassiopeia, shaped like a W. The W was upside down, forming an M (for mountain?) over Kibo, and it guided me through the night. Twice I saw shooting stars, like fireworks celebrating our summit. I took the time to take out my iPod and started playing music to keep me going. Five years ago I lost track entirely of the night, and 7 hours merged into memories of only about an hour. Not this time: I played about three hours of Metallica and the Doors, and then Guns N’ Roses. At 5 am, I was actually dancing with the porters on the mountain, gyrating as they sang, then playing air guitar to Welcome to the Jungle….

And then the iPod died. I knew from then on it would be a struggle. While hoping to summit at 7, our group was slow. This was good as no one got sick, but it depleted that much more energy. The guides forced Red Bull down us, which I detest but drank. It instantly gave us energy. Stinger waffle snacks, Gu gel, hot tea, anything to keep us energized. But the energy drained away. I bonked. I had been running on music and fumes and now my music was gone. It did a psychological number on me. Why didn’t I keep a second iPod in my other pocket! (Note to self for next time…)

And then the iPod died. I knew from then on it would be a struggle. While hoping to summit at 7, our group was slow. This was good as no one got sick, but it depleted that much more energy. The guides forced Red Bull down us, which I detest but drank. It instantly gave us energy. Stinger waffle snacks, Gu gel, hot tea, anything to keep us energized. But the energy drained away. I bonked. I had been running on music and fumes and now my music was gone. It did a psychological number on me. Why didn’t I keep a second iPod in my other pocket! (Note to self for next time…)

I thought about the kids I know who struggle with hemophilia and poverty. This suffering was ordinary, a luxury, self-imposed. No big deal. Just put one foot in front of the other. The trouble was, my feet would not always respond to my commands! Victor took my arm and guided me, assuring I would not stop or sit. Sitting down was the kiss of death on the summit climb and was not permitted.

Mike was now doing great, finally over his food poisoning and feeling strong. Amazing! Jim was confidently plugging away, and never once seemed to fatigue. Rich Gaton and I climbed closely together, with his daughters. Without their mom there, I felt a deep need to stay close to the girls. They are strong, but I had done this climb before and knew the pitfalls. Self-doubt, giving in to fatigue, wanting to quit—been there, done that. Rich and I conversed, which was nice, as it kept our minds off the fatigue. Dawn broke behind us, a red orb peaking through the clouds below us. Funny, sunrise was happening below us! Above us, the summit.

Day 5: August 11, 2016 Summit Day!

Incredibly, we reached Stella point at the brilliant dawn of day, at 18, 848 feet. This was a milestone for sure, and you could see Uhuru Point, at 19,349 feet, the official summit, up ahead. It seemed so close and, in my mind, addled by lack of oxygen, I thought it was only a ten minute walk. I told this to Taylor, who was exhausted and ever so politely said, “I think I’ll stay here at Stella,” and sank to a rock. We cajoled her, and I told her just ten more minutes! Think of how you will feel if you stop now! Hesbon pulled her up and she stumbled on. I needed Victor too to guide me on. The ten minutes was actually another hour! Perhaps the hardest hour of the entire six days was getting from Stella to Uhuru, but we all did it.

We hugged, we posed for photos with our Save One Life banner, and actually explained to some fellow summiters what the program was all about. I looked about at the view I couldn’t see five years ago when I first summited. There are no words: a massive volcano, with a deep caldera of lifeless moondust, shocked with gargantuan glaciers. The glaciers are blue tinted rectangular structures that you could compare to alien spaceships, or modern architectural skyscrapers or, as Taylor put it, like the rocket popsicles we ate as kids. I struggled to find a way to describe their icy beauty, like frozen fortresses on display for millions of years.

We needed to get down as oxygen is only 50% at the summit. We linked up one by one: Jim, Mike, Rich, Samantha, Taylor, me, our guides, and started the descent. Eric and Andrew were already on their way down. This would take over 5 hours and was another punishing trip. But for now, we gleefully focused on the goal we achieved and worked so hard for: the summit. Somewhere in my oxygen-deprived head, I was also thinking of what this could mean for Save One Life and the patients we serve. Money for programs; motivation to keep persevering despite setbacks and challenges; and perhaps, another summit climb, when more captains of industry like Rich, Eric and Mike join us to experience the outer limits of endurance, to raise money and awareness for hemophilia in developing countries, and to triumph, personally and professionally. When there is a common cause to help others who suffer, a purpose bigger than ourselves there seems to be no limits to what a group of compassionate people can accomplish.

We needed to get down as oxygen is only 50% at the summit. We linked up one by one: Jim, Mike, Rich, Samantha, Taylor, me, our guides, and started the descent. Eric and Andrew were already on their way down. This would take over 5 hours and was another punishing trip. But for now, we gleefully focused on the goal we achieved and worked so hard for: the summit. Somewhere in my oxygen-deprived head, I was also thinking of what this could mean for Save One Life and the patients we serve. Money for programs; motivation to keep persevering despite setbacks and challenges; and perhaps, another summit climb, when more captains of industry like Rich, Eric and Mike join us to experience the outer limits of endurance, to raise money and awareness for hemophilia in developing countries, and to triumph, personally and professionally. When there is a common cause to help others who suffer, a purpose bigger than ourselves there seems to be no limits to what a group of compassionate people can accomplish.

Thanks to my teammates—you are strong, exceptional, compassionate and brave! In particular, thanks to Eric Hill for suggesting this climb and for his leadership, and to Dr. Jim Palmer for his advice, services and wonderful attitude! Thanks to Team Kilimanjaro for safely escorting us on this amazing journey. Thanks to everyone who contributed to our fundraiser, for you made this climb successful and worthwhile. Please visit Save One Life to learn more about how to sponsor a child with hemophilia in need, or to get involved. Get ready for the Kilimanjaro CEO Challenge… 2017?