“I speak of Africa… “

|

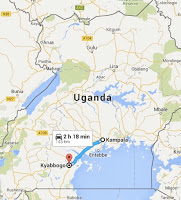

| By our calculations–5 hours! |

I speak of Africa and golden joys—William

Shakespeare from Henry IV, Part II c. 1597

|

| Kampala farmer’s market |

Last Saturday, April 23, Agnes Kisakye, the executive secretary of HFU, arrived in a hired van at 7:30 at my hotel, the Sheraton

Kampala, which is perched atop one of Kampala’s seven hills. We first stopped at the city square

market for bananas for breakfast. I didn’t get out of the van, but we were

swallowed up in a swarm of Ugandans, all busy shopping, negotiating prices,

filling plastic bags with fruit. A hive of frantic activity. The bananas–called kabaragara--were

small and sweet and I devoured three. The day was cool with blue skies. We were

ready for a long road trip, south of Kampala.

|

| Carrying banana leaves |

|

| Scenes as we leave Kampala |

It turned out to be way longer that we thought. A

three-hour trip became 5+ hours trying to find this one family in Kyabbogo. At

least we had a very comfortable van and Agnes is a great travel companion. She

is only 29, but very mature, socially conscientious and dedicated. She’s a registered social worker, and I was quite

impressed by her. I wish I could have tape-recorded the things she said; so much wisdom, though I knew many of these things because it’s the same in so many

countries. Her brother Joseph, now an MP (member of parliament), is the person who contacted me back in 2008 requesting help.

|

| Tea plantations |

[In fact, Agnes reminded me that I was the first to help Uganda. In 2008 an Indian working in

Uganda who had a child with hemophilia, Satish Pillai, emailed me about setting up a

foundation, and getting factor for his son. We worked together through email only, and he did all the groundwork in establishing the HFU. Satish later had to return to Mumbai, India but

appointed Joseph Ssewungu, a headteacher and father of a child with hemophilia, to replace him. Joseph and I had a

few emails back and forth, and in one he mentioned he had read my book, Raising

a Child with Hemophilia. I found that amazing. But eventually things quieted, and other countries in need diverted my

attention.

|

| Beauty of Uganda |

We stopped en route to buy groceries for the families. Though it

was just a little street market store, we got carried away and spend $120.

Agnes seemed aghast at how freely I spent money; she was hesitant to suggest

anything because she didn’t want to take what she thought was all my money. We

bought rice, sugar, salt, Coca-Cola, cookies, lollipops, Vaseline (“For their

skin,” Agnes said), soap—lots of soap—tea, loaves of bread, and cooking oil.

Christian. We agreed that this work was our calling in life, and nothing could

stop us from helping the poor and suffering. I asked her when she knew she wanted to be

a social worker.

recalled, “since I was young. I wasn’t sure exactly what I would do. But I

loved it, the idea that I would make a difference in someone’s life. I always

wanted to start an organization. I said to my friend one day, ‘You and I will

start an organization to help people’.”

It hasn’t been easy trying to get the Haemophilia Foundation of Uganda

off the ground. “Being a volunteer is difficult. Some people show interest and

start to help us, but later they quit. I used to work as a volunteer for an

NGO, for HIV/AIDS education.” But when Satish left, she felt compelled to help

her brother full time. Now she volunteers full time, Monday through Friday and

many a weekend, to run the HFU. There are days when she stays at the Mulago

Hospital all day and into the evening—meeting with doctors and staff, and

counseling patients.

a right, and the road deteriorated from paved to dirt roads, rowdy and

unpredictable. We had stopped many times along the way, to ask locals on the

side of the road where we were going. The frequent stops allowed me to drink in

the fleeting scenery: the dusty, red clay roads that branched off from the

highway and paved roads, forming a network like blood vessels throughout the

country. Everyone seemed to move at the same pace, languid, at ease. There are no beggars and everyone works. Down one alley, a small child

in shorts and plastic sandals lugs a huge blue plastic container with water and

disappears into a slum. Roadside shops sit shoulder to shoulder: one sells

tires, one sells headboards for a bed, unvarnished and raw, another sells colorful

clothes and markets them on stark white mannequins, oddly out of place. Some

young men wearing dusty clothes and a few teen girls in worn and damaged dresses—obviously

donated (one is a shiny party outfit; one looks like a Halloween Tinkerbell

costume; another is a tight club dress) wait patiently at a pump while a young

man furiously wields the handle to draw water from the community well; a small wooden

cart belches thick smoke from the meat cooking on it, filling the air with a delicious

smell of beef, and I realize I am suddenly hungry; plump women, wearing

colorful wraps around their waist and patterned turbans to protect their hair

from the dust, balance fruit and vegetables on their head to sell or to bring

home; three little children, the dust turning the color of their deep brown

skin to chalk, dance in rhythm to the music pulsating from a radio in front of

a store while an adult eggs them on. Everyone is barefoot, or at most

wearing just sandals or plastic flip-flops.

if they are not too shy, they break into beaming smiles and wave. It’s

encouraged to wave back, and I try to keep the window down when we ask for

directions so I can wave. “Muzungu!”

they shout sometimes, their word for anyone not from Uganda, though mostly it

refers to white people. It’s not a slur; it’s just their word, much like when

the children of Haiti shouted “Blanc!” (White!) when they saw me, and tried to

touch my white skin.

gives way to hard red clay, with shoulders that sag, and the van rocks back

and forth with the unevenness. The rains and traffic have created deep ruts. We

roll up the windows as the van’s tires churn the clay to powder. Now the roadside stands have disappeared and only solitary homes are

spied through the thick vegetation. The homes for the most part are nice for

rural homes. Mud poured into a wood frame, and hardened, with a thatched roof,

or brick, made by hand, with a corrugated steel roof. Everything is cinnamon red.

Red dirt road, red brick homes, red-rusted steel roofs. Red and green are the

colors of Uganda.

with slums, poor hygiene, noise, pollution, alcohol, crowding, waste—but access

to hospitals and health care. There are megaslums, which defy the imagination,

where residents live like ants in an unhealthy and often dangerous colony. And

there is rural poverty, with lush vegetation, farm lands, rich soil,

fresh air, room to grow—but a lack of transportation, customers, and most of

all, lack of health care. Still, the scenery is beautiful, even if poor.

Agnes says, “That’s witchcraft.” Noting my raised eyebrows, she continued.

“Witchcraft is still practiced here, especially in rural areas. That would be a

witchdoctor’s place to meet with families. He will diagnose someone, and then

offer a remedy. It is so crazy! He might say, ‘Take the fingernail clippings of

your child with hemophilia, of the parents, of the relatives. Now go throw

those in the river. The river will carry them away and with it, the disease. Your

child will be cured.’ Or he may take some backcloth and banana leaves and wrap

up some part of the person—their hair, for example—and say now the disease is

buried.”

witchdoctor will first do a bit of research. “He checks with other people who

work with him, to learn more about the patient. What are their symptoms? Who is

sick? Who has been sick in the family? Then when the family goes to see him, he

will say, ‘It is your child that is sick?’ Yes! ‘He bleeds a lot?’ Yes! So it

looks to the family like he is magical and knows everything.”

|

| The Kajimbo family: four boys with hemophilia |

Going to a witchdoctor sounds quaint, but it is anything

but cheap. In a country where the average annual salary is $500, and an

educated physician earns about $200 a month, a witchdoctor can charge anywhere

from $100 to $300—a session! This is the power of culture, traditional beliefs

and desperation. Health clinics are hard to find and far away. Rural families

become victim to their limited education, isolation, and the charisma of the

witchdoctors. “There are no government policies or laws regarding witchdoctors,”

Agnes adds.

destination: a vermilion brick-and-mortar home with a spacious front yard of

dirt, and surrounded out back by farming fields. This is where the Kajimbo

family lives. We unfolded ourselves out of the van and stretched, smiling at

the children who gathered in curiosity. The sun warmed our visit. We decided

first to get acquainted, and then to bring in the gifts. The mother Harriett

and father Richard came out of the house first, and shook hands, he smiling

reservedly, she smiling in anticipation. The first thing I noticed was that

their clothes were remarkably clean compared to their surroundings, as though

they had just changed. Harriett’s eyes sparkled, and her hair was a woven

masterpiece, plaited to perfection. Her dress was bright blue and white. Richard

wore a comfortable blue polo shirt and khaki pants. They were in great contrast

to the children, who were dressed in stained and torn clothes, and who went

barefoot, and had dirty face and hands. It was incongruent.

|

| Laurie Kelley with baby Joel |

Still, the children seemed happy and at ease, and

deeply curious. We entered their home. There was no where for the family to

sit, so they congregated on a rug covering the packed earthen floor.

The baby, Joel, was fat and happy, and I was thrilled to take him, diaperless—always

a calculated risk—into my arms, and jiggle him on my knee. Agnes and I were

given the one bench in the welcoming room. Each child came to us one at a time,

and reached out to shake hands while bending deeply down on their knees; this

is a sign of respect for elders, and not easy to do for children with joint

deformities.

|

| Inside the red brick home: earthen floors |

Introductions: Six children, four with

hemophilia. Bad odds. January, age 15; Emmanuel, age 13; Richard, age 9; and

Ronald, age 5. January smiled but looked a bit stunned; Emmanuel had a ready,

warm, friendly smile, as if he had been expecting us at long last; Richard

conjured a mischievous smile, which made you wonder what he was thinking; and

Ronald tightened his lips at us, refusing to surrender any hospitality. But my,

were they all beautiful children. A sister sidled in through the raggedy

curtain that separated the welcoming room from the other five rooms. Josephine

seemed shy but wanted desperately to make friends with us.

laughing in no time. A pod of neighborhood children plugged the doorway,

leaning in, eyes wide open in astonishment. The driver had brought some bags

over by now, and we handed out lollipops first—no barriers were left after

that. The children saw at once that they came first. There were plenty to share

with the neighborhood children, which no doubt boosted the reputation of the

Kajimbo family. But Ronald still did not smile.

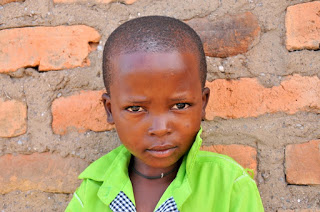

|

| Ronald |

|

| Emmanuel |

Agnes explained Save One Life to them, and also

that I was a mother of a child with hemophilia. This tidbit also breaks

down barriers instantly. Harriett looked at me with widened eyes now. After the

overview, we did the enrollment forms, starting with January. The enrollment

was easy as there wasn’t much information, and all of it was the same for all

four kids. They all missed an entire term (out of three annually) last year due

to bleeds. School is five miles away, and they often cannot walk the distance. They

can’t afford transportation to take them to school. When they do go to school,

they sometimes get “caned,” beaten with a reed or stick for infractions. This

is old-school British and still acceptable here. January goes to school with

8-year-olds in primary 3, because he is so far behind. This embarrasses him. He

gets no treatment; Mulago Hospital in Kampala is five hours away and requires a

motorbike ride on the rough, unfinished road we just conquered, and then

waiting for a public bus to take to the capital. And it costs $50, while

the family’s monthly income is $15-$30.

|

| Richard |

|

| January |

We surveyed the house: they have no electricity,

running water, indoor toilet or plumbing, or refrigerator. The floors are

concrete or red packed soil. Cloth doors separate the six rooms and it’s

impossible to stay clean, as dust coats everything. Out back, a brick shed for

cooking, an outhouse, and one rib-showing, starved black and white dog

collapsed in the heat. All the kids—same story. What do they do when not in

school? “Digging in the garden,” which means they do chores: farming, seeding,

harvesting. Harriett is only 29, with six kids, a huge responsibility. Still,

she smiles happily as she takes Joel from me.

school, or help feed them. We share the butter, rice, sugar and supplies with

Harriett, who is overwhelmed by our generosity. We hand out toys, many of them

simple, donated toys, especially the super-heroes and plastic creatures that have sat

in a basket for two years in my basement. I finally dumped the last of them in

my duffel bag, and now, Ronald holds what looks like a silver Power

Ranger-wannabe in his hands. He is dumbfounded, then catches on, then finally….

Breaks into a huge smile. Boys just love action figures, no matter where they

are.

photos. We photograph January’s knee, particularly his prominent scar from surgery,

before he was diagnosed. He reminds me of Mitch from Haiti, who also almost

died from surgery before being diagnosed.

with a surprise: a chicken! Agnes laughs and I hold it for a photo opp. They offer the chicken as a token of their appreciation. The poor thing had its legs

trussed up and was hung upside down, then laid on the floor, immobile. Its eyes bulging, fearful, waiting to know its fate: lunch, dinner? Were we to take it back five hours to Kampala like that? I wondered what the Sheraton staff would say if I walked in with a chicken. I had to refuse, even though

this was impolite. Agnes explained to the families that I love animals and could not bear to

see it like this. The lucky chicken was paroled and January took it back outside.

As we prepare to leave, we do a

family picture, with me holding Joel. Harriett comes out of the house, and suddenly drops to her knees before me, and

holds my hand. This is unusual for an adult, I think, and I thank her but also

encourage her to stand up.

|

| The Kajimbo’s kitchen |

We are happy when we leave, and once back on

paved ground, we stop at a hotel for lunch, feeding the drivers as well. I don’t

each much, but enjoy a Coke immensely. Agnes and I talk about what can be done

for the family, what their daily life must be like. How much $.73 a day–the cost of a sponsorship from Save One Life, will impact their life. It might be the best thing that will ever happen to them.

|

| Agnes Kisakye and the Kajimbo boys |

|

| My chicken! |