Andes Survivor Expedition: Resilience, Dignity, Strength

Resilience is not the ability to recover. It is the ability to go through hell, to endure

Resilience is not the ability to recover. It is the ability to go through hell, to endurethe indescribable, and not to break. —Pedro Algorta, survivor

It was a story heard around the world in 1972—the “Miracle of the Andes,” some called it. It’s

a story that tore at hearts, shocked others, made new believers of God, and made some turn away from faith forever. It’s a story you couldn’t make up, that plumbed the depths of the human heart and soul. How does one survive the impossible, and still retain dignity, humor, compassion, teamwork?

a story that tore at hearts, shocked others, made new believers of God, and made some turn away from faith forever. It’s a story you couldn’t make up, that plumbed the depths of the human heart and soul. How does one survive the impossible, and still retain dignity, humor, compassion, teamwork?

I have yet to meet anyone in my life who has not heard of the Andes plane crash survivors. To me, the story encompasses everything about life you might need to know. It is the story itself of life. And the survivors, including the ones who survived impact but perished before rescue, are heroes of mythical proportions. That is, until you meet one of them. I was privileged to meet Eduardo Strauch last week, on an expedition into the Andes, where we would have the chance to go to the crash site. We spent the entire week together, along with ten other guests from Argentina, Spain, the US and the UK. And our two guides, Ricardo Peña of Alpine Expeditions, and geologist Ulyana Horodyskyj.

Eduardo walked in to the hotel lobby in Mendoza, Argentina, to meet our group, and seemed like a nobly aging warrior off the pages of a graphic novel. I have read three books on the subject, the classic book Alive by Piers Paul Read (three times), Miracles

of the Andes, by survivor Nando Parredo (two times) and I Had to Survive by Roberto Canessa (two times). I’m currently reading Pedro Algorta’s book Into the Mountains. Nando and Roberto were the two survivors who literally climbed out of the Andes, after 60 days on the mountain, to seek help. (To this day, it seems utterly superhuman and impossible.) I have watched the movie Alive countless times.

of the Andes, by survivor Nando Parredo (two times) and I Had to Survive by Roberto Canessa (two times). I’m currently reading Pedro Algorta’s book Into the Mountains. Nando and Roberto were the two survivors who literally climbed out of the Andes, after 60 days on the mountain, to seek help. (To this day, it seems utterly superhuman and impossible.) I have watched the movie Alive countless times.

To meet Eduardo was to meet someone legendary. Nowhere in history is there a story quite like that of the Andes survivors. Eduardo is at once dignified and friendly; a man with

To meet Eduardo was to meet someone legendary. Nowhere in history is there a story quite like that of the Andes survivors. Eduardo is at once dignified and friendly; a man withan incredible history, and story to tell, who lives in the moment; famous, but makes you feel as though you are the important one. We instantly liked him, and our frozen awe began to thaw to a warm friendship feeling. He is truly a wonderful person to know.

We spent a week together traveling to the foothills of the Andes far outside of Mendoza. A four-hour car ride, then we arrived at a farm of sorts, where we each got a horse, and loaded our things for the week onto mules. At 70, Eduardo is handsome, fit and at ease

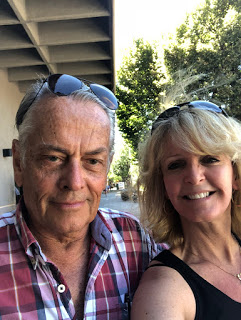

on a horse. With me was Angela Forsyth, a physical therapist from New Jersey, who works for Diplomat and who I’ve known for probably 20 years. Our first day then was this

four-hour car ride followed by a four-hour horseback ride across an incredibly windy

flatland that threatened to permanently remove my cowboy hat, then up winding dirt paths into the mountains. We crossed several rushing rivers that swept the accompanying, yelping dogs downstream and soaked our hiking boots. We made camp that evening in a beautiful little valley, where the majestic Andes towered all about us. We also had a small team with us to cook, handle the horses, and help out with packing.

on a horse. With me was Angela Forsyth, a physical therapist from New Jersey, who works for Diplomat and who I’ve known for probably 20 years. Our first day then was this

four-hour car ride followed by a four-hour horseback ride across an incredibly windy

flatland that threatened to permanently remove my cowboy hat, then up winding dirt paths into the mountains. We crossed several rushing rivers that swept the accompanying, yelping dogs downstream and soaked our hiking boots. We made camp that evening in a beautiful little valley, where the majestic Andes towered all about us. We also had a small team with us to cook, handle the horses, and help out with packing.

The next day, Wednesday, we took a seven-hour roundtrip horseback ride up treacherously tricky slopes, covered with nothing but rocks—the poor horses!—often at 45° angles. It seemed we should have rode mountain goats instead of horses, but the

The next day, Wednesday, we took a seven-hour roundtrip horseback ride up treacherously tricky slopes, covered with nothing but rocks—the poor horses!—often at 45° angles. It seemed we should have rode mountain goats instead of horses, but thesteeds handled it well, though they often looked quite wary. Our reward was a beautiful

mountain lagoon, left over from a glacial runoff.

The next day only about half our group went to the crash site, another seven-hour roundtrip horseback ride. The rest of us, me included, came down with either bronchial

issues from the tremendous dust kicked up by the horses as we rode, or a virus that

hitched a ride from Spain with Clara, one of the guests. Was I disappointed not to get to the crash site, which was the whole point of the expedition? Not really. First, Clara, the lady from Spain, is the niece of one of the young men who died on impact from the crash. It was more important that she go to the site with Eduardo. She had been sick the day before, but she rallied, and they went.

issues from the tremendous dust kicked up by the horses as we rode, or a virus that

hitched a ride from Spain with Clara, one of the guests. Was I disappointed not to get to the crash site, which was the whole point of the expedition? Not really. First, Clara, the lady from Spain, is the niece of one of the young men who died on impact from the crash. It was more important that she go to the site with Eduardo. She had been sick the day before, but she rallied, and they went.

Second, I felt privileged to meet Eduardo, a survivor of this terrible yet timeless event, and that was enough for me. He sat with us in the evening after dinner in the mess tent, and answered our many questions about his experience. Our questions were candid but sensitive. We asked him about leadership: how and when did he and his two cousins become the de facto leaders of the group? About the role of women: how did the boys treat one another after Liliana, the “mother” of the group, died in the avalanche? (Without her feminine presence, the boys became a bit more aggressive with one another) About faith: did this experience deepen his faith in God? (The Read book made much of the issue of faith. Answer: no) About survivor’s guilt: did he suffer from it? (No) The worst part of the experience? (The avalanche)

Second, I felt privileged to meet Eduardo, a survivor of this terrible yet timeless event, and that was enough for me. He sat with us in the evening after dinner in the mess tent, and answered our many questions about his experience. Our questions were candid but sensitive. We asked him about leadership: how and when did he and his two cousins become the de facto leaders of the group? About the role of women: how did the boys treat one another after Liliana, the “mother” of the group, died in the avalanche? (Without her feminine presence, the boys became a bit more aggressive with one another) About faith: did this experience deepen his faith in God? (The Read book made much of the issue of faith. Answer: no) About survivor’s guilt: did he suffer from it? (No) The worst part of the experience? (The avalanche)We were enthralled. We were like students listening to a sensei. And yet, the more Eduardo shared, the more he seemed like a regular person, not a mythical hero, which I know he does not want to be seen as. I saw how odd it is to put him, or anyone, on a

pedestal. He is relatable, real, though his experience was surreal. We ate dinners together as a group, shared stories, teased one another, laughed, chatted about normal things. We shared a laugh when Ricardo wanted to put Angie and me in one very small tent. We are not ones to complain but… Ricardo looked over at Eduardo’s larger tent and said, “Well, maybe I could ask Eduardo…” But I said,

no, whatever Eduardo wants, Eduardo gets. But after looking again at the small tent… I said to go ahead and please ask Eduardo. I apologized later for kicking my hero out of his tent! He laughed and graciously accepted the swap.

pedestal. He is relatable, real, though his experience was surreal. We ate dinners together as a group, shared stories, teased one another, laughed, chatted about normal things. We shared a laugh when Ricardo wanted to put Angie and me in one very small tent. We are not ones to complain but… Ricardo looked over at Eduardo’s larger tent and said, “Well, maybe I could ask Eduardo…” But I said,

no, whatever Eduardo wants, Eduardo gets. But after looking again at the small tent… I said to go ahead and please ask Eduardo. I apologized later for kicking my hero out of his tent! He laughed and graciously accepted the swap.

If you are interested in leadership, teamwork, faith and survival under the harshest of

conditions, read the books I mentioned. At the very least, watch the movie Alive. When you ask people about the greatest survival story ever, most people will mention Shackleton and the failed Antarctic expedition. But he has nothing on this story. To me, the Andes plane crash story is the greatest story of survival, and I have read so many. It’s a story of deepest humanity, of people at

their best.

conditions, read the books I mentioned. At the very least, watch the movie Alive. When you ask people about the greatest survival story ever, most people will mention Shackleton and the failed Antarctic expedition. But he has nothing on this story. To me, the Andes plane crash story is the greatest story of survival, and I have read so many. It’s a story of deepest humanity, of people at

their best.

I asked Eduardo on our last day, as we stopped at a tienda for cold drinks en route home, if he

could tell my readers one or two things he took away from his experience, what he would tell us?** “First, the power of love,” he replied. When you lose everything, and can rely only on one another,

you learn the true meaning of love. “Love is everything. We loved one another and cared for one another up there. And our love for our families back home kept us going.” The second thing?

could tell my readers one or two things he took away from his experience, what he would tell us?** “First, the power of love,” he replied. When you lose everything, and can rely only on one another,

you learn the true meaning of love. “Love is everything. We loved one another and cared for one another up there. And our love for our families back home kept us going.” The second thing?

While Nando and Roberto disappeared into the Andes for 10 days, Eduardo was left with the 13

others to wait, never knowing whether a rescue would come, whether the two had fallen into a crevasse, or were killed in an avalanche or simply starved to death. Their epic climb out got all the headlines, but it took incredible strength to simply wait in the fuselage and not give up hope.

others to wait, never knowing whether a rescue would come, whether the two had fallen into a crevasse, or were killed in an avalanche or simply starved to death. Their epic climb out got all the headlines, but it took incredible strength to simply wait in the fuselage and not give up hope.

“You have more strength in you than you will ever know,” he said to me assuredly, knowingly.

**Roughly quoted, as I did not have my notebook with me. Apologies to Eduardo for

any misquotation.

any misquotation.

To learn more about the Andes Survivor Expedition: www.AlpineExpeditions.com

Eduardo Strauch has written his own account of his ordeal, Desde el silencio (Out of the Silence) available on Amazon.com