The Bloody Wars: When War Advanced Blood Transfusion

Scientists and physicians in the warring nations during World War II struggled to save soldiers bleeding to

death on the battlefield. Dragging injured soldiers back to field hospitals resulted in too many lost lives. But what other alternative was there?

In Spain, he seized on this innovative idea: to take the blood donated by civilians in bottles to wounded soldiers near the front lines. Being highly adaptable and effective, Bethune’s service is regarded as one of the most significant military-medical achievements of the Spanish Civil War. A benchmark in

the history of mobile medical achievements, his work later inspired MASH units.

The more precise and cautious physician, Duran-Jorda ran a sophisticated operation in Barcelona. He collected only O blood; oxygenated the bottles; and ensured high standards of safety by testing rigorously. He had vehicles fitted with refrigerators to transport the blood to front line hospitals. In February 1939, Duran-Jorda fled to England, where he helped the British develop their blood banks for the front line.

The more precise and cautious physician, Duran-Jorda ran a sophisticated operation in Barcelona. He collected only O blood; oxygenated the bottles; and ensured high standards of safety by testing rigorously. He had vehicles fitted with refrigerators to transport the blood to front line hospitals. In February 1939, Duran-Jorda fled to England, where he helped the British develop their blood banks for the front line.

when the Nazis came to power. Blood now represented racial purity—with the belief that only pure German blood could be used in German soldiers to save their lives. This would cost the Germans thousands of lives.

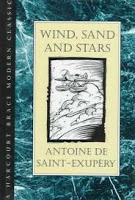

Fantastic Book I Just Read

Wind, Sand and Stars by Antoine de Saint-Exupery

I had long heard that this story was a classic in travel reading. The story of Saint-Exupery’s flights over Africa as a mail carrier for the French postal service, Aeropostale in the 1930s. Told in the first-person voice, Saint-Exupery shares his views from the airplane seat, and from his fertile mind. The text is lyrical, mesmerizing, fluid. An adventurer, he writes: “The call that stirred you must torment all men. Whether we dub it sacrifice, or poetry, or adventure, it is always the same voice that calls. But domestic security has succeeded in crushing out that part in us that is capable of heeding the call. We scarcely quiver; we beat our wings once or twice and fall back into our barnyard.” His crash and struggle to survive in the Sahara is riveting. A rousing five/five stars. Read it!