A year ago we renewed a match between two heavy-weight contenders in hemophilia: plasma-derived products versus recombinant. The question: which product is more likely to cause inhibitor formation? In the fight to avoid inhibitor formation, some groups and opinion leaders read the initial results of the SIPPET project and declared plasma-derived the winner. But it’s a bit more complicated than that. Read Paul Clement’s excellent article on SIPPET; it will take many more rounds before we declare an outcome. The good news is that so much clinical scrutiny is underway.

The SIPPET

Bombshell

Paul Clement

A bombshell was dropped at the Plenary Scientific Session of

the 57th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology (ASH) on December

6, 2015, in Orlando. Study coordinators of the SIPPET project (Study on

Inhibitors in Plasma-Product Exposed Toddlers)1 presented surprising

preliminary findings: recombinant factor VIII products are associated with an

87% increased risk of inhibitor development compared to plasma-derived factor

VIII products. 2

In other

words, for every 10 people treated with recombinant factor VIII as opposed to

plasma-derived factor VIII, 1 patient can be expected to develop high-titer

inhibitors.

As a parent

of a toddler who does not have inhibitors, you may feel stunned, angry, or

scared when you read these findings. Should you be? Before you rush to make a

product change, learn how the study was conducted, what its potential

shortfalls are, and why you should take a deep breath!

Shock and Awe

Understandably, many consumers are concerned. Some news

releases describing the study results only heightened the alarm. Hemophilia

Federation of America (HFA) issued a press release requesting that National

Hemophilia Foundation’s (NHF) Medical and Scientific Advisory Council (MASAC)

“consider the temporary suspension of recommendations… that state any

preference for recombinant factor products until the results of the full SIPPET

study can be reviewed.” 3

Is this a

reasonable reaction, or is this jumping the gun? It helps to examine how the

study was conducted—and why.

Fighting Invaders

Why was the study looking to see if plasma-derived products

are less immunogenic than recombinant products—that is, less likely to lead to

developing inhibitors?

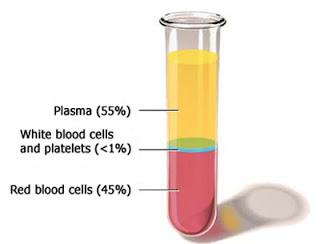

In the

blood, factor VIII is normally tightly bound to another protein called von

Willebrand factor (VWF). VWF has several functions, including protecting factor

VIII from being digested and cleared from the bloodstream. Some researchers

suggest that in doing this, VWF masks some of the sites on the factor VIII

protein where antibodies attach, potentially making factor VIII with VWF less

immunogenic. Note:

•

Intermediate/high-purity plasma-derived factor VIII products are the only ones

that contain VWF.

•

Recombinant and ultra-high-purity (monoclonal purified) plasma-derived factor

VIII products contain no VWF.

Without the protection of its VWF “bodyguard,” the immune

system may recognize these factor VIII products as intruders and develop

inhibitors to neutralize them.

The problem is, no one really knows for sure what causes

inhibitors, and no one knows whether factor VIII with VWF is less immunogenic.

SIPPET Strategy

SIPPET set out to answer this question: Is plasma-derived

factor VIII with VWF less immunogenic compared to recombinant factor VIII

without VWF?

SIPPET

researchers designed a study called a prospective

randomized controlled trial (RCT). Prospective means looking forward,

before the patient has developed an inhibitor (in contrast to retrospective studies, in which

researchers look backward, after someone has developed an inhibitor).

Controlled means that there are two groups: (1) an experimental group that will

use factor VIII containing VWF, and (2) a control group that will use factor VIII

without VWF. This second group is used as a standard of comparison against the

experimental group. Randomized means that no one involved in the study

influenced which group a patient was assigned to. Randomization is often done

by a computer.

RCT studies

are often considered the gold standard, thought to produce more reliable data

than other types of studies. Although an RCT can show relationships between

variables being studied, it cannot prove causality. So the RCT used for SIPPET

can’t prove that the presence or absence of VWF in factor VIII caused the observed results.

SIPPET was

conducted between 2010 and 2015, and data was collected on 251 patients from 42

participating sites in 14 countries from Africa, the Americas, Asia, and

Europe. The patients were younger than six years old, had severe hemophilia A,

were previously untreated with factor, and had minimal exposure (less than five

times) to blood components. Of the 251 patients, 125 were treated with one of

the plasma-derived factor VIII products containing VWF. The remaining 126

patients were treated with a VWF-free recombinant factor VIII product.4 The

patients were followed to see if they developed an inhibitor, for 50 exposure

days (days they received factor infusions) or three years, whichever came

first.

It’s

important to note that only one of

the plasma-derived products used in this study is available in the US, and that

the study was funded by manufacturers of plasma-derived products. Is this a

conflict of interest? Does it influence the findings?

SIPPET Shortcomings?

The preliminary findings were startling: of the 251

patients, 76 developed an inhibitor, and 50 of those were high-titer

inhibitors. And 90% of these inhibitors developed in the first 20 days of

treatment. Most important: recombinant factor VIII products were associated

with an 87% increased risk of developing an inhibitor compared to

plasma-derived factor VIII products containing VWF.

Remember, these are not final results and have not yet

been reviewed by researchers outside of the study. Before you decide

whether to switch your toddler to a plasma-derived factor VIII containing VWF,

know that many other variables affect inhibitor formation. In any experiment,

variables not directly being tested, but which could have an effect on the

outcome, are called confounding variables.

For

example, the single greatest risk factor for developing inhibitors is the type

of genetic mutation that caused your child’s hemophilia. If the mutation in the

factor VIII gene resulted in no factor VIII being produced in his body, then he

is already at significantly higher risk of developing an inhibitor. This is one

of many confounding variables in the SIPPET study.

One way to

reduce the effects of confounding variables on the data is to use a large study

sample. If the sample size is large enough and patients are randomly assigned

to two groups, then each group should have about the same number of patients

with the same confounding variable, so its effect will be canceled. The problem

is that the more confounding variables you have, the larger your study sample

size must be—perhaps several thousand patients. And many variables affect

inhibitor development.

Another way

to account for the effects of confounding variables is to identify and measure

them, and then to separately compare and analyze the data from patients who

share the same confounding variable. This process is called stratification (meaning to separate into

layers) and was used by SIPPET along with other statistical analysis methods.

But the study identified and measured only six confounding variables: (1) age

at first treatment, (2) intensity of treatment, (3) type of factor VIII gene

mutation, (4) family history, (5) ethnicity, and (6) country site. What about

the effects of the other confounding variables that were not measured? If the

study sample size was too small to reduce the effects of other, unmeasured,

confounding variables, then the study’s conclusions are questionable and might

be explained in other ways.

Don’t Jump Ship Yet

At the time of this writing, SIPPET has not been published

in a medical journal. That means researchers—outside of those conducting the

study—don’t know much more about the study than you do after reading this

article. Only a short synopsis of the SIPPET study was presented at the ASH

annual meeting—just enough to cause a stir and raise many questions. You can be

sure that as soon as the journal article is released, it will be examined by

bleeding disorder experts worldwide. Questions will undoubtedly be asked about

the handling of confounding variables and whether the study sample size was

large enough.

And experts

will have another question, too: Why didn’t the study include any of the new

prolonged half-life products, several of which appear to have a lower

immunogenicity than other recombinant factor VIII products?

Should you

switch your toddler from a recombinant to a plasma-derived factor VIII product

containing VWF based on the preliminary SIPPET results, in the hope that it

will reduce the risk of developing an inhibitor? This is a question for you and

your hematologist, but if you were a betting person, the answer would be no. To

bleeding disorder experts, the results of SIPPET are not a bombshell, but

merely a piece of the puzzle that is inhibitors.5 The conclusions of this study

contradict those of several other studies. It may take years, and several

additional studies, to sort everything out. MASAC is on top of this, and as the

data becomes available, you can be assured that NHF will share its expert

opinion. So keep calm and carry on!

1.

https://ash.confex.com/ash/2015/webprogram/Paper82866.html (accessed Feb. 7,

2016).

2. Inhibitors are

a major complication of hemophilia in which a person’s immune system mistakenly

recognizes infused factor as a foreign (and potentially dangerous) protein, and

develops antibodies (inhibitors) to inactivate the factor, making factor

infusions ineffective.

3.

http://www.hemophiliafed.org/news-stories/2015/12/update-2-sippet-study-2/

(accessed Feb. 7, 2016).

4. The VWF-rich

plasma-derived factor VIII concentrates used by SIPPET: Alphanate (Grifols),

Fandhi (Grifols), Emoclot (Kedrion), or Factane (LFB). The VWF-free recombinant

factor VIII products used: Recombinate (Baxalta), Advate (Baxalta), Kogenate SF

(Bayer), or Refacto AF (Pfizer).

5. Visit the

Believe Limited website for an excellent interview by Patrick James Lynch of

bleeding disorder expert Dr. Steven Pipe about the SIPPET findings:

http://believeltd.com/inhibitors-sippet-and-the-double-edged-internet/

(accessed Feb. 7, 2016).