Into the Andes

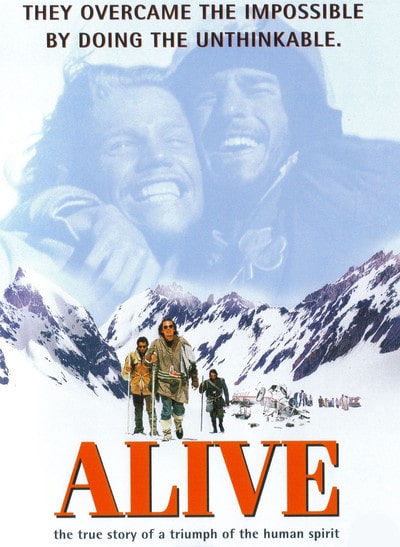

Part 1 of an adventure. Two years ago I set out into the Andes on horseback to visit the rustic memorial and ultimate site of the 1972 plane crash in the “Valley of Tears” deep in the Andes, that took the lives of 29 people. It was called “The Miracle of the Andes” because 16 did survive the most extreme and harsh experience imaginable. It’s been documented in many books, the 1993 movie “Alive” and many documentaries on YouTube. In 2018 I only made it to base camp, because of a bad respiratory infection. But because this story hit home, and stayed with me for decades, I knew I couldn’t accept my defeat. I returned again January 4, 2020 to Argentina, to rejoin Alpine Expeditions leader Ricardo Peña and wife Uly, and survivor Eduardo Strauch, and eight others to journey days and hours into the Andes, to see the crash site, to absorb the beauty of the mountains, to feel this unique and amazing experience. Here, I’ll discuss the trip itself. Next week, I’ll share thought about the “Alive” story and how it relates to leadership and hemophilia. Leadership has been on my mind lately, and in fact, in the February issue of PEN, we will discuss changing leadership and leadership challenges in 2020.

You can’t be a leader unless you have someone or something to lead. On Sunday January 5, our new team all met up at 2:30 at the Hotel Raices Aconcagua, where we loaded our bags onto the bus. It was great to see Eduardo Strauch again, who I met two years ago. He gave me a big hug, and immediately said he wanted to learn more about my charity work in hemophilia. This was very kind, as he is a huge celebrity, and has met hundreds of people all over the world. In other words, his time, thoughts and energy is valuable and limited, and I was so pleased he was interested in hemophilia. Our new team consisted of five people from the US, one from New Zealand, one from the Netherlands and one from Scotland. All in all, it was a great team, and team dynamics showed themselves early on, in terms of who connected and how.

The next morning Monday, January 6, I had a quick breakfast at the hotel, and we started our trip to the Andes. This involved a two hour bus ride to a pit stop, a little restaurant we visited last time, with the same little dachshund puttering about! A few people recognized Eduardo, which was cool.

Then, off again for a two hour, very bumpy, grinding ride to the foothills. The ride was much rougher than I remembered. I did well, though, although I had picked up yet another respiratory infection just before leaving Boston, and was coughing the whole time and indeed, am still coughing as I write this blog.

We drove up the tight turns and rocky roads, where black rocks dotted the landscape with shocks of yellow straw-grass coming straight out of them, looking like so many surprised, stone-faced troll dolls.

Around 2:30 pm we reached the horse post, where Sybille, Victor, Juan and Veronica greeted us. They are our support team. It was late in the day to begin our ride to base camp at 8,000 feet, but we first had to have lunch. Sybille laid out a great lunch, and we munched on cheese, peanuts, olives, pickled onions, ham and soft drinks. Though Sybille put out wine, Ricardo forbade it as it is dehydrating. The Andes is extremely dusty and arid, and alcohol doesn’t mix well with altitude. Soon, we saddled up the horses and we were ready to head out for four days.

The wind whipped us and the dust coated everything at once. We couldn’t speak, as the wind roared in our ears. It was nonetheless enchanting, to see the sloping sides of the Andes mountains climb upwards toward their pinnacles. The Cordillera de los Andes are the longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The Andes are the second highest mountain range on earth, after the Himalayas. But no facts can describe their beauty, their majesty. Greens, golds, browns, tans… all colors seeping and weeping down from the summits.

Across rivulets, up steep trails, then down steep, dusty paths which made the horses jolt and rock. Then across a pounding glacial river, which sank the horses up to their chests and caused them to step cautiously on the slippery rock bottom. We anticipated being pitched into the glacial-cold water, but they are surefooted and not one ever stumbled. Each of us was in our own internal world as the wind struck our ears. But by 7:30 pm we reached camp at last. The kitchen and mess tent were already set up; we got to work unpacking. I set up my tent with Uly’s help (Uly is a glacial geologist): a green Hornet by Nemo. I was excited to be back in a tent and in a sleeping bag, believe it or not. Dinner was at 10:30 pm, pasta. Eduardo welcomed everyone to ask questions–about anything. And this is significant, because his experience was so extreme in the annals of human survivor stories. I asked a lot of questions, particularly about the Exit sign he mentions in his book (I’ll share more about this next week).

Most people recall the 1972 crash of the rugby players for one sensational aspect: the survivors had to eat the bodies of the dead. There was no other option, except to die. While this is the trigger that makes mostly people recall the story, whenever you read the books, or watch the movie or documentaries, it is to me the least important aspect; it’s just a fact. What stands out to me is how the survivors adjusted, created a mini-society, supported one another… all things I will discuss next week. And indeed, just like two years ago, the topic of food source didn’t really come up. In fact, what surprised me most was when Eduardo said that throughout his whole ordeal—the subzero temperatures, the starvation, the altitude, the death of his best friend, eating the flesh of the dead—it was the chronic thirst that was most unbearable.

Tuesday, January 7, we headed to the crash site. This would be a long day, and an emotional one. I awoke around 6:30 am in my little tent, and did not sleep well: the dust is insidious, the wind relentless. My coughing kept me up, and it was the reason I placed my tent far from the others.

I could hear stomping near my tent early in the morning as the arrieros got the horses untied and ready. I dusted myself off, and shook off dust from the sleeping bag, and dressed. It’s not that cold, maybe only dropping to 35° or 40° at night. Breakfast was hot scrambled eggs, muesli, tea and toast, served by the pretty Veronica. We saddled up the horses around 9:45 am. It took four long hours to get to the Valle de las Lágrimas, the Valley of Tears. The weather was perfect: not too hot, sunny, no clouds. Only the strong mountain winds sliced through the valley and kicked up perpetual dust. Our horses carried us over long, winding mountain trails, hemmed in by towering slopes of the Andes. We passed a few green glacial pools; the mountains are denuded, due to the arid conditions. The wind simply erodes anything trying to grow. It was hard to take pictures with the horses rocking, and the wind pounding us.

On a special trip like this, it truly helps to have a guide like Ricardo, who first discovered Eduardo’s jacket in 2005, while climbing in the valley. He returned it to Eduardo, they became fast friends and the rest is history! Their friendship allows us to enjoy the beauty of the Andes, the experience of a survivor, a rough and excitong trip, and learn about geology and glaciers from Uly. (To learn more visit Alpine Expeditions)

Finally, at 3 pm, we could see the Valley of Tears, and the high ridge where the Fairchild first struck the mountain. Beneath it, the steep slope on which the Fairchild tobagganed, and finally impacted to a halt. We could see the little mound in the foreground with the rustic iron cross, signifying the memorial.

We dismounted and waited for the remaining riders. I was stunned when Eduardo took my elbow and guided me to the foot of the small ridge where the memorial waited. He wanted me to ascend with him. Only me. This impacted me greatly; it was an incredible honor. And when we reached the top after a few steps. I became so emotional. Me, who never cries. And never in public. I have read this story so often, like the others on this trip. The victims’ names are all familiar: Liliana, Marcelo, Arturo, Rafael, Susy, Diego, Numa, Enrique, Gustavo… and now we were here. Where their bodies lie in the cold, remote cradle of the Andes, I felt emotions well up that I have hardly ever felt. Tears seeped out, and Eduardo and I hugged briefly. He knows what this place does to people. He knows why they come. This is where his life totally changed. And his story—their story—has changed our lives. Surrounded by the towering, stark mountains we love and with hard rocks at our feet, our hearts felt at once heavy with regret and sadness, and yet alive with hope. These victims will never be forgotten. And people like me pay for the privilege to travel an arduous journey to be a small part of this.

Eduardo knows all this. He told me earlier that one year he stayed behind while the group went off to explore, and one of the horse handlers began talking to him. The handler confided that his son had committed suicide a few years before. And for a while, he considered it himself, too. But it was the “Alive” story, and the visit to the crash site and memorial that changed his heart. These Uruguayan boys were not given a choice; many died. The ones who lived fought with superhuman strength mentally, emotionally and physically to stay alive. One almost feels like honoring them by staying alive too, no matter how badly you feel. I told Eduardo, All that you endured then has meant something these 48 years. How many lives have you impacted and perhaps saved, simply by trying to stay alive?

Eduardo walked to the small pile of debris, where pieces of the Fairchild were gathered: parts of the ceiling, the walls, scrap metal, signs, gears. I’m sure some hikers take pieces home as trophies, but this is discouraged. At the rusty iron cross, there is a mound where people place meaningful items, despite a sign asking people not to in Spanish. I forgot this rule, and took out a beautiful string of prayer beads with a silver cross, made by my friend Cazandra MacDonald, to lay on the memorial. We placed it near a painted rock signed by the children of Liliana Methol, who died in the avalanche on the 16th day. Then we move it to where the bodies are buried: Eduardo accompanied me, and we had Ricardo take our photo, for my friend Caz. Eduardo put his arm around me and said, “I’m so happy you’re here.”

I felt I must apologize to Eduardo for being so emotional: I didn’t know these people personally, and this certainly is not my story; it’s his. But all of us cannot help but relate, for whatever reason. I think of their immense suffering, their sacrifices, the lost potential of these precious young people. This story is one of life: it is of trauma, tragedy, survival, suffering in the extreme, endurance, human spirit, courage, strength, love, community, fear, hunger, thirst, faith, loss, hope and rescue. Everything in life is in this story. Perhaps it’s why so many people can relate to it. There is so much to this story.

Beyond the ridge where the memorial and grave lie, up ahead, is the actual crash site. We can clearly see it, but it is another hike to go there. I see the front wheels of the Fairchild in the valley below to the right. To my left, at the base of the ridge up ahead, I see the tail stabilizer, sitting there for 48 years. The wind kicks up and the others decide to go down into the valley; they will stay the night. I’ll return to base camp with Eduardo, and three other members of our team.

While Eduardo sat to eat a sandwich, I ventured over to the tail stabilizer, where two tall hikers were. I asked them to take a picture of me with the tail, and they happily complied. Their English is perfect; they are two 32-year-olds, Gonzalo and Eduardo, on a multi-day hike. They were not even that familiar with the Alive story. When I mentioned that Eduardo Strauch was with me (a fact they probably knew, as many people come when Ricardo and Eduardo come here, just to catch a glimpse of Eduardo), I invited them to come meet him. They were almost taken aback, like it was too great an honor. And they know that our team has paid for this privilege. But after reading Eduardo’s book, Out of the Silence, which is about the most important lesson learned–love– I told them I knew he would welcome meeting them. We walked over to Eduardo, and as I thought, he was warm and kind to them. And they were completely respectful.

I asked if they are hungry, and they startled almost, then politely said no. But I knew they were hungry. I gave them some cookies from our stash, and they were in heaven. They had been subsisting on trail mix for three days and the sugar in the cookies made them so happy! Gonzolo jokingly said, “I love you!”, in between bites.

We decided we need to return, as the weather was getting more threatening. It was another three and a half hours back, on horses. And it was now 3:45 pm. As we jostled down on our horses, the wind kicked up again and my cowboy hat flew off and away, down into the deep, deep valley, where it will never be seen again.

We passed one mountain that was brilliant in colors: like huge slabs of gelato on display, first milk chocolate, then mint chocolate, then coconut, then butterscotch, then double chocolate. At 6 pm we saw an arriero riding fast across the trail, coming towards us, a large package draped across his horse. We were shocked to know that our team didn’t have a the tent for those staying overnight! And what a night it turned out to be. For us at base camp, 40-50 mph winds, pounding our tents, making it impossible to sleep, and endless sprays of fine dust. For those at the crash site, hurricane force winds and bitter cold, so much like those nights 48 years ago, when a group of Uruguayan teenage boys, wearing only street clothes, with no food or survival gear, somehow survived a horrific crash, watched their friends die yet found the will, courage and leadership to survive 72 days in the Valley of Tears.

Next week: Leadership lessons from the Andes.

To participate, visit: Alpine Expeditions

To learn more about the survivors experience, read Alive, by Pier Paul Reads, Miracle of the Andes by Nando Parrado, I Had to Survive, by Roberto Canessa, and of course, Out of the Silence, by Eduardo Strauch, all available in Amazon and in English