Simon’s Story

Today we met a very special person with hemophilia, who touched us deeply, and reminded us of why we do the crazy things we so—like driving about three hours outside of Nairobi, deep into the Kenyan countryside just to meet one patient. Well, this is why we call our nonprofit “Save One Life.” It’s all about one person at a time.

You cannot separate Simon’s story from the logistics. Sure, he has hemophilia, as does his brother. He’s 26. His wife left him, and he now lives on his mother’s farm. He has the usual untreated bleeds, and hobbles about on crippled legs. We wanted to meet him because we knew he lived in difficult circumstances. Total rural living; you might say primitive, if you judged him by the average American standards.

We headed out at 8 am with Maureen Miruka, founder of the Jose Memorial Hemophilia Society, driving. With us were Paul, a 21-year-old with hemophilia, impeccably dressed as always, and Jeff, our videographer. They picked me up at the Holiday Inn, and off we went.

Over two hours of driving on a highway, dodging the worst potholes you can imagine. The shoulders of the road drop swiftly, so we have to be careful not to veer off. It was like a high-speed obstacle course! Left, right, fast, slow, then the random speed bump. The speed bumps (or “sleeping policemen”) are not marked, and so blend in with the road, and can cause severe damage. The ride seemed to take a lot longer than two hours.

We took a short break to see the breathtaking Rift Valley, 3,600 miles long, and an important source of fossils.

We arrived in Nyahururu, far north of Nairobi, a bustling town. As always, the Kenyans are dressed well, and walking, walking, walking. It seems that everyone walks in this country. I was surprised to see a long line of young men with motorcycles, just waiting. This was local transport, and in a minute I would find out why.

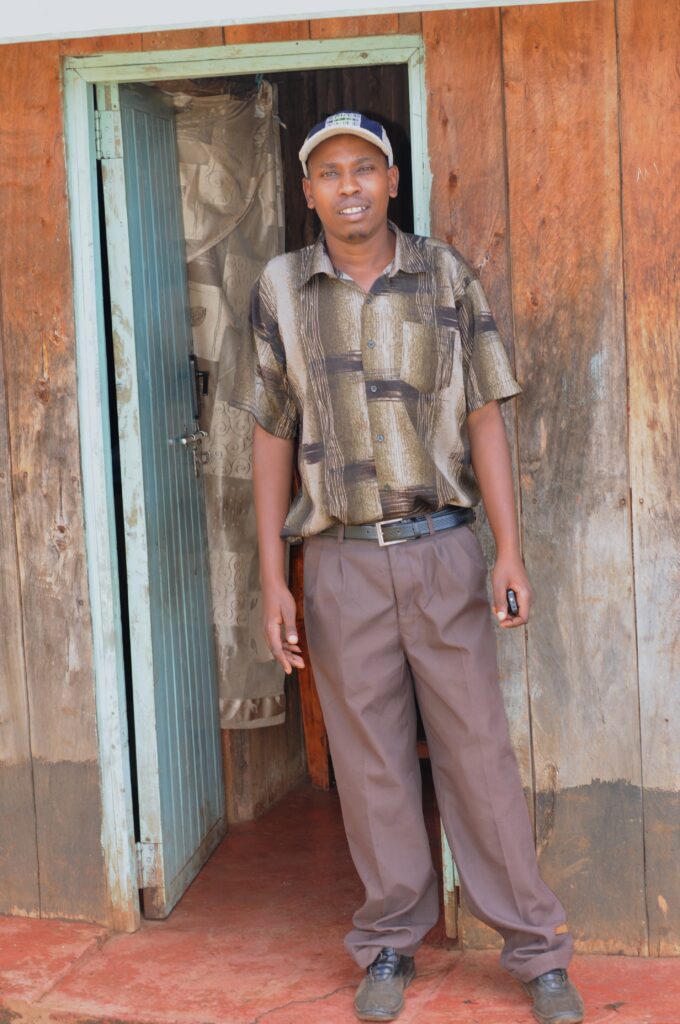

We spotted Simon under a gas station sign, waiting for us. I gave up my front seat when I saw how painfully and slowly he was walking, to give him more room and excluded room. Simon would show us how to get to his home.

We turned the corner to Simon’s street. The street is a dirt road off the main road. The red, rich soil of Kenya covers every inch of this long road. Up we went, as the road ascended and we dodged not potholes, but regular bikes with massive loads of grass or wood, their drives pushing them resolutely upwards. Or women and children carrying huge loads of potatoes in sacks, supported by bands around their heads. Or cows, stumbling down the road into town.

We spun in the soil, which was muddy at times, and began to wonder how on earth Simon could manage this. We finally arrived at his farm, perched high on a hilltop with a spectacular view of Kenya. To get to his farm you must climb up another dirt pathway strewn with rocks.

The logistics of getting him help for a bleed are mindboggling. When Simon gets a bleed, this is what happens:

Simon, in pain, has to either walk down the dirt path to the dirt road, then walk over three miles on this dirt road, down the hill and into town. Then he has to wait for the local bus to drive him to Nairobi, to the only hospitals that know how to care for people with hemophilia. Our drive took over two hours, and that was going fast. On a bus, you can expect to take two to three times longer as it makes stops, and goes slower.

All the time, Simon is in great pain.

We arrived probably with our mouths gaping: the farm is rustic but pretty and what a view! His mother greeted us, but wasn’t smiling, the way Kenyans usually are when they smile. Indeed, the entire family was grim, and tight-lipped. “They are stressed,” Maureen said to me aside.

We sat inside the small home (we would call this a shed) where his mother lives. I glanced around and noticed the corrugated tin roof (nothing new there; this is a given in the developing world) and cardboard. The walls were split logs, and the “wallpaper,” or covering, was cardboard, through which the light peeped in.

We chatted with Simon a long while, recording his family history and discussing his bleeding pattern. This would give us the necessary information to register him with Save One Life and find him a sponsor. Jeff also gave him an interview, and Simon spoke in Kiswahili, the national language, as his English is very limited. He shared his frustration, not at hemophilia, but of the incredibly long distances he must cover just to get some kind of help.

It was clear to us all that Simon needed to keep factor at home. To my delight I learned that he had been taught to self-infuse. But the government of Kenya buys no factor, and so there rarely is any available. Imagine traveling all that way in terrible pain only to arrive at the hospital and be told there is no factor! Or, come back tomorrow for your FFP.

Simon’s mother surprised us with a wonderful home cooked meal: mokimo, a national dish. It was the only meal we would eat all day (and only my second meal in two days!!). Things started to lighten up a bit. We presented Simon with a gift of factor VIII; we shared how Save One Life would provide funds for transportation. And we pledged somehow we’d keep him stocked with factor. By the time we shuffled back to the car, everyone was beaming, like a little ray of light brightening his future.

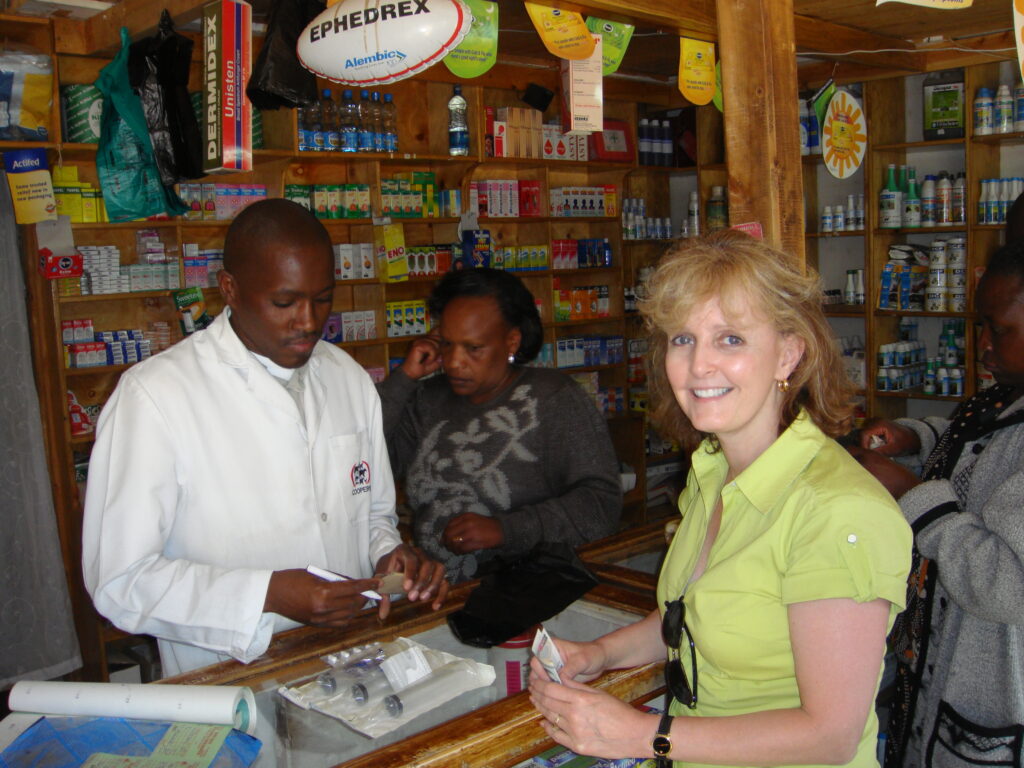

Before we left, we stopped at the local pharmacy where I bought Simon syringes, needles and medical tape. Things we so take for granted are not free here! And some cash so Simon could ride one of those taxi-motorbikes back up the hill to his home.

The ride back was both sobering and exciting. We had defined ways to help this very special man.

Our day was far from done. The ride back—three hours again—was only to plan what to do about another young man, age 21, hemophilia A, in a mental institution. He was placed there following the post-election violence that engulfed Nairobi last fall. This young man’s home was invaded, ransacked and then burned to the ground by electrified hoodlums, as many homes burned all around. I don’t know his whole story: perhaps he was chased, terrorized. Whatever it was, it left him so traumatized and depressed, he had to be committed. We heard he was able to leave now, following two months of treatment.

The problem? His mother, single, with two boys with hemophilia and two nieces, has to pay $340, a fortune, perhaps more than what she makes in a year. The son would not be released unless this was paid. This is the way it is in developing countries. We actually drove at twilight to go see him. We were allowed into the padlocked Men’s Ward, and the rank smell of human beings unable to care for themselves assaulted us. Lying on cot after cot were young men, about 25, all heavily sedated for the evening. The boy’s mother was with us as we tried to wake he son. He awoke and stared at us blankly, through drugged eyes. He looked so small and helpless on the old, thin cot. My God, I thought. This could have been my 22-year-old.

I made the only decision I possibly could; I gave the money to Paul, and tomorrow (Thursday) he would go with the mother and bring this poor child home, where his family could care for him.

This was a day of pure experience and exploration in the lives of two young men in desperate need. We cannot fix everything or everyone, but our motto at Save One Life is “To save one life is to save the world,” and that works just fine for me.