At least

something

at the Dallas meeting was older than me—the NHF! This is my 24th

year of attending NHF meetings and I was thrilled to catch up with so many

colleagues and friends.

|

Kim C. and John Urgo

of RUSH, with Zoraida |

“Boots on the Ground” refers, I think, to our

exceptional advocacy work, a history of which I liken to the Big Bang theory. At

one time there was darkness out of which an explosion heard around the universe

occurred, and new stars were born. The darkness, of course, was the HIV era,

the “holocaust” in the words of many, when half our already small community was

decimated by contaminants in the nation’s blood supply and blood-products used

for clotting blood. The Big Bang was the outcry from patients, who formed

groups like the Committee of Ten Thousand, and later Hemophilia Federation of

America, to take on corporate America and the government of the United States

itself. These people—Corey Dubin, Dana Kuhn, Tom Fahey, Val Bias and more—were

our stars, emerging through that dark time. Many of our stars have burned out, passed

away, but many still burn bright.

|

Laurie Kelley with Texas hemophilia friends Andy Matthews

and the famous Barry Haarde! |

They’ve now harnessed all that energy,

knowledge and power and shine it on industry and insurance companies,

protecting our need for safe products, available products and access to all

products. And with them are hundreds of families who have joined that cause.

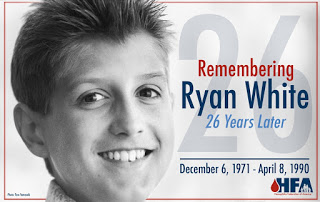

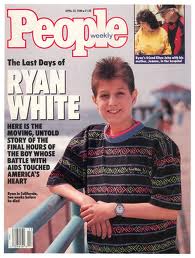

To remind us all of where our advocacy comes

from, NHF spotlighted Ryan White, one of our community’s first advocate,

certainly our first child advocate. An Indiana native, Ryan won the right for

all children to attend school who had hemophilia and AIDS; his mother Jean

White was interviewed and I think we all had tears, when she teared up. There

are not enough words to express how courageous that boy was.

NHF Chair Jorge de la Riva gave an

impassioned speech that praised the efforts of all our community to stand up

and protect our needs and rights. He also challenged us all to look deep within

to ask What more can we do? Can I do? We can all do something.

NHF CEO Val Bias’ speech stood out for his

challenge to include the fringe members of our community, especially women with

bleeding disorders (who are really not just carriers), inhibitor families and

those with rare bleeding disorders, like factor XIII. Indeed, he called out to

those members to stand and be welcomed, and the audience exploded into applause

when an entire row arose.

I would add to that the LGBT community, which

has existed quietly. And yet they are some of our greatest activists. Don’t know

what LGBT stands for? It’s time to look it up, and get to know them.

|

Someone older than me? Joe Pugliese,

my oldest friend in hemophilia |

Pharmacokinetic testing was a hot topic: how

does your child react to infused factor, especially if he is on prophy? Only

one way to learn how quickly the factor fades over time from his body. Not

every child can be prescribed a three-times-a-week, Monday/Wednesday/Friday

prophy regimen. Running a blood test consecutively over a few days to test his

levels will reveal how quickly factor is used up—in other words, what’s his

unique half-life? This topic dovetails perfectly with the release of our

one-time newsletter YOU, arriving in your mailbox soon! It’s all about your

child or loved one with hemophilia’s unique needs, including his or her

particular half-life, so vital to know.

One huge change I noticed? Years ago,

specialty pharmacies and homecare companies dominated the exhibit hall floors,

with stuffed bulls to ride and take a photo with) and even once a huge pirate

ship (remember the pirate ship anyone?). These companies outdid each other in a

bid to get potential consumers to their Vegas-style booths. Now, they have

shrunken to little booths on the periphery, while the megabooths and choice

space goes to pharma. Why? Specialty pharmacies have consolidated into a few

monster, dominant entities. They don’t have to compete for business anymore;

they own us. Pharma on the other hand, is competing fiercely for your attention

with a glutted pipeline of products in clinical studies. Prepare for lots of

pharma advertising in the new year.

Please go on line and read up on the

three-day annual event, which brought treatment staff from HTCs, consumers,

nonprofits, manufacturers and homecare companies all together for hours of

learning and connection. Congratulations, NHF, on another successful year!

Keep these boots on the ground,

with sharp spurs.

More photos from the event to come!

Good Book I Just Read

How to Love [Kindle]

Thich Nhat Hanh

Short essays on the nature of love, peace and

how to find these traits within so you can better encourage the transfer of these to others in need. Like all

Hanh’s books, it is easy to read and leaves you feeling more tranquil and

loving. Three/five stars.

In August 1990, four months after White’s death, Congress enacted The Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency (CARE) Act (often known simply as the Ryan White Care Act), in his honor. The act is the United States’ largest federally funded program for people living with HIV/AIDS. The Ryan White Care Act funds programs to improve availability of care for low-income, uninsured and under-insured victims of AIDS and their families. The legislation was reenacted in 1996, 2000, 2006, and 2009, and is now called the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program.

In August 1990, four months after White’s death, Congress enacted The Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency (CARE) Act (often known simply as the Ryan White Care Act), in his honor. The act is the United States’ largest federally funded program for people living with HIV/AIDS. The Ryan White Care Act funds programs to improve availability of care for low-income, uninsured and under-insured victims of AIDS and their families. The legislation was reenacted in 1996, 2000, 2006, and 2009, and is now called the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program.

Ryan eventually found a school that welcomed him in Cicero, Indiana: Hamilton Heights High School. He thrived there.

Ryan eventually found a school that welcomed him in Cicero, Indiana: Hamilton Heights High School. He thrived there.