“Human pieces of geometry”: Brian of Zimbabwe

I’m in Zambia, Zimbabwe’s huge neighbor to the north, having a hot tea on the deck of my lodge room on the

banks of the Zambezi. The sun is a scorcher today, the air humid as if someone

dropped a huge, wet blanket over the atmosphere. While I see Africa’s beauty

before me, I’m haunted by the image of an African boy in Zimbabwe. Though I

left Zimbabwe on Wednesday, my mind still drifts back, wondering what to do.

Zambia next Sunday and finish Zim here.

The Health Minister was unavailable to meet, but we did get to meet with the personal health advisor to the president, the charming Dr. Timothy Stamps, who I have met twice before. We chatted about

hemophilia, and it’s good to have someone like him in government who knows about it. But even more important, we have the National Blood Transfusion Service, which is really the backbone of hemophilia care in Zimbabwe. David Mvere, the director, is an advocate for those with hemophilia—and always ready to help us when we have product to donate. I’ve met him several times over the past 12

years. We will work together to see if we cannot move hemophilia care forward in 2013. What’s needed is a national “tender,” in which the government advertises that is has so many dollars to spend on hemophilia products. The drug companies then bid for the sale, keeping their proposed price tags secret from one another so the government can take advantage of the lowest price/highest quality drug. Zim hasn’t had a tender in almost 20 years, I think.

results.

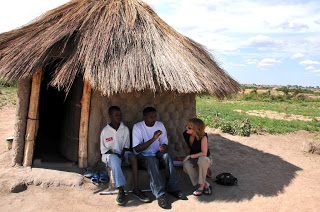

patients go for treatment. Little Brian had been admitted. Simbarashe Maziveyi,

the ZHA president, chatted with him in Shona, the native language to learn more

about his case. Simba would have made a great professional counselor; his calm demeanor, listening skills and reassurance touch everyone.

We meet with Dr. Dyana, the Cuban

hematologist who chose to stay in Zimbabwe to help cancer and hemophilia

patients. Thankfully she did because Zim suffered for many long years without a

single hematologist in a country of approximately 500 patients.

also happens to be a Save One Life beneficiary. He lives with his wife and small daughter in a 12×12 room—just a room—with all his worldly possessions: a small TV, some clothes, a few books. He has not worked since January, and you can see the anguish in his face. How do they eat? Where do they get money from? Save One Life gives him some cash. His sister lives nearby and helps out. But they are desperately poor. Vincent does own a bicycle, which he proudly shows me. He can bike to the treatment center when he has a bleed.

Talk about out of pocket costs: how is

a destitute guy from a rural area ever going to pay this off? Might the hospital

refuse him treatment if he doesn’t pay? Maybe. Simba pledges to go talk to

officials on his behalf. This is really the value of going to visit patients.

The founders of the Flying Doctors of Africa (now AMFAR) once said that if you

want for patients in Africa to come to you, they’ll die; you need to go visit

them. I take that to heart.

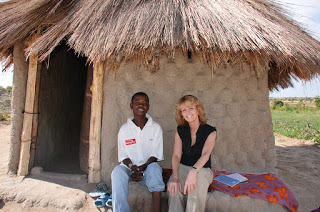

On Tuesday we have a patient meeting,

with as many families as possible in attendance. Some have come from hours away

by bus. Many are in pain, seeking relief. Some of the moms are single, and

confide their fear about how to get financial relief, and how to treat bleeds.

Someone asks about a cure; another about gum bleeds.

heads, we ask for a volunteer among them to organize a home-infusion training day. It’s a go, and the moms pledge to get together; the wife of one man with hemophilia is a nurse and she offers to be trainer. It’s a positive thing to at least start with.

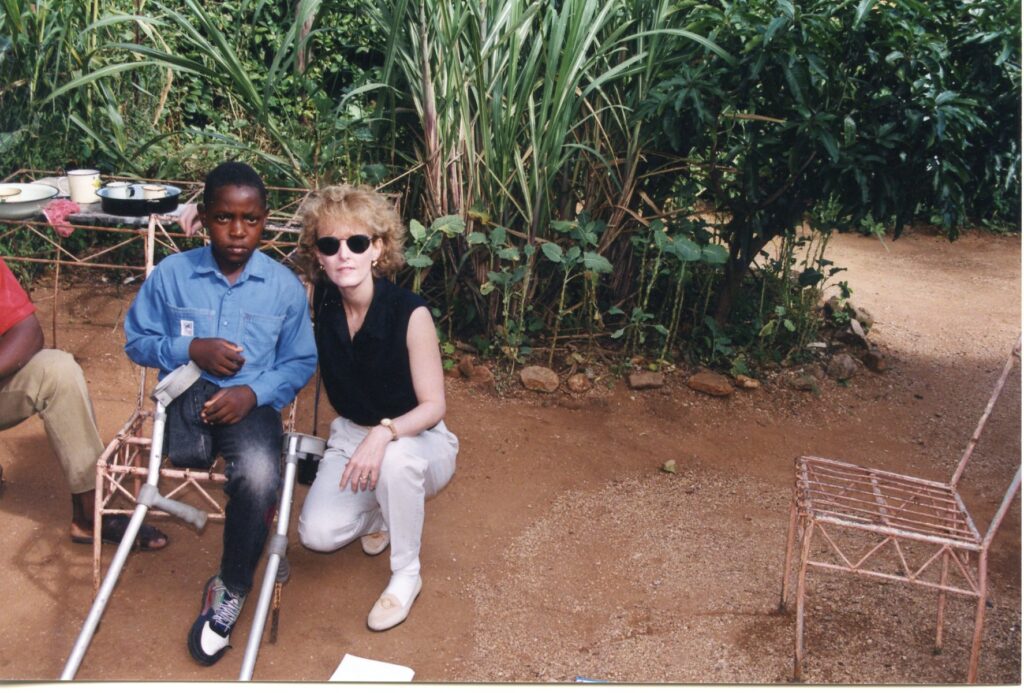

On Wednesday, as I prepare to leave for the airport, Simba begs just one more visit. Often it’s when I am feeling tired, burned out just want to get on with the next leg of the journey or even go home, that the most important child is met. This happened Wednesday.

founder of the World Federation of Hemophilia: that patients with hemophilia were “human pieces of geometry” stuck in a wheelchair. Only this little triangle boy didn’t even have a wheelchair.

My heart broke for this child, an orphan, being raised by his grandmother in a rural village, where he will no doubt be blamed for this disorder because of witchcraft. When I asked Brian to lift his arm, to see if he could at all extend it, he had to lift it at the shoulder, but lacked the muscles to lift his arm, and was prevented from

searing pain.

It’s comforting to know that Brian is loved, but it eats at us that our children in developed countries enjoy every benefit of medicine and can lead normal lives. Brian is stuck in a time-warp: care will come to Zimbabwe, of that I am sure, but not perhaps in time for this

one precious child.