Research: As in War, so in Medicine

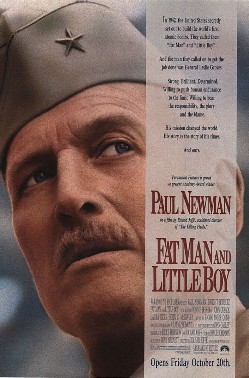

I should have written this blog last night, as it was the 75th anniversary of dropping the plutonium bomb on Nagasaki, Japan, which effectively ended World War II. Instead of writing about this, I watched the excellent movie “Fat Man and Little Boy” (1989), directed by Roland Joffé and starring Paul Newman. It details the creation of the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos, New Mexico, where top nuclear physics scientists are corralled in secrecy, racing to create the doomsday bomb before the Nazis do. It took only 19 months of intense, crazy pressure, and about $2 billion to create the first two thermonuclear weapons, used on Hiroshima (Aug 6,1945) and Nagasaki (Aug 9,1945). These remain the only times when nuclear weapons were used in war. It’s estimated over a quarter of a million Japanese died.

In the race to complete the bombs, scientists nationwide raised moral questions: should we even do this? At what cost in lives? The Nazis had surrendered by then and Hitler was dead; did we need to drop this on Japan? The moral questions were ultimately pushed aside in the quest to finish the project and end the war fast.

What made me startle was the dollar amount tossed out by General Leslie Groves, who headed the project: $2 billion in research. This is equivalent to about $28 billion today!

I thought about the costs estimated for gene therapy for hemophilia, estimated at $2 million per person. We all balk at this, but I also think about the amount of time, energy, expertise, investment and expectations that determine this price. Watching the Manhattan Project take shape and unfold in the movie, you’re amazed at level of intelligence of the scientists, the personal and professional sacrifices they make, the intensity of research. We see that happening now with a race to find a vaccine for COVID-19. What does it take, how long, and at what cost?

The bombs ended the war. Japan surrendered on September 2, 1945 in a humiliating defeat. Research that caused massive and sudden death and destruction for a final victory. The moral dilemma: was this research for good or for evil?

We’re now racing to defeat another enemy in war: COVID-19. Almost any cost is bearable, yet we are at odds with one another at what costs, and how much. The inconvenience of wearing masks? Laughable when we watch the sacrifices of those in World War II, or any war. Loss of livelihood? A serious sacrifice. Loss of life? No question. Any cost, any inconvenience.

In hemophilia, there was a time when we were at war, with HIV. We raced to find methods to kill HIV in the blood supply, and then to create recombinant products (not from human plasma). Now we have the luxury of time. Current standard factor products in the US are excellent, plentiful, accessible. Expensive, yes, but we have them. And we have ways to pay for them. Gene therapy will be a luxury product at first, and very expensive. It will be a challenge to convince payers to cover this, but we believe ultimately in access to all therapies. Freedom. As in war, so in medicine.

And no matter how you look at it or what the cost, it is still expensive research to cover, but research for the good.