|

Laurie Kelley en route to

Everest base camp |

Everest Base Camp Journal Part 2

Why do people subject themselves to hardship and

even personal risk to climb a remote mountain, or in my case, just to gaze upon

one? I learned on the second part of the Everest base camp trek that when you

meet the mountain, you are meeting yourself. To get to base camp requires

suffering long before you start through hard core training, then the trek

itself with all its deprivations, illness and discomfort, and for what? It’s to

see a mountain that most will never see. But it’s also to see a side of

yourself you might never see. The mountain holds a mirror to you, showing you

inner parts that are not apparent unless pain and testing bring them forth.

Sometimes you are angry with yourself—you allowed yourself to be ill, fall

behind, complain. Sometimes, you are surprised: I did it! I climbed that baby!

Sometimes, you are amazed: not only did I overcome, but I did it with grace and

appreciation.

These are the things you

learn by undertaking these journeys. But the mountain is only a metaphor,

because anything that unveils your deeper inner self involves risk and

suffering: being a parent, being in a relationship, going to school, trying for

a new job or career, getting healthy, overcoming a severe illness… a chronic

illness, like hemophilia. Pushing yourself into a new terrain, to learn, to

try, to even fail. When it is over, you know more about who you are, and what

you can do, and what is possible.

Chris Bombardier, a young man with hemophilia from Denver,

Colorado, is pushing his limits to see what he can do, not just

for himself but for all people with hemophilia; not so that everyone will climb

a mountain, but as a metaphor

for what is possible, what can be overcome, and to find out who we are as

individuals.

|

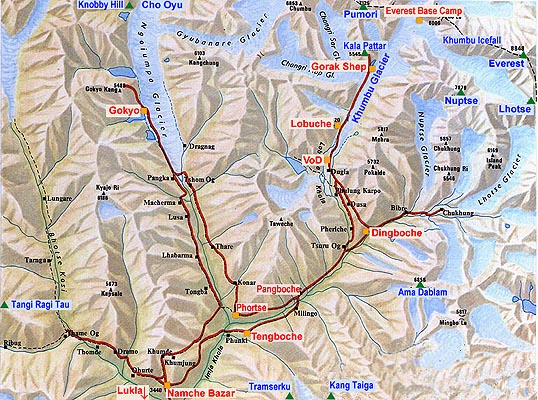

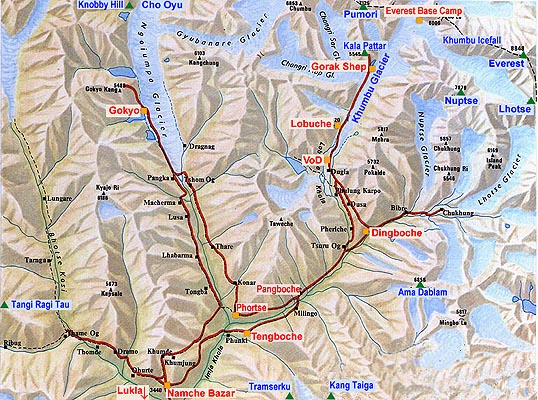

| Our rugged route for 9 days |

Friday April 7, 2017

“… the climbers I know all love life and fight

furiously to hold on to it, and the same restless energy and enthusiasm helps

them overcome the problems of everyday life and is transmitted to those around

them.” Joe Tasker and

Chris Bonington, Savage

Arena

I was awake at 5 am in my lovely room at the

“Rivendell” tea house. I had a

fabulous night’s sleep but it was freezing in the room. The

extreme cold sapped my cell phone batteries, and I realized I needed to start

sleeping with all my batteries. I had scrambled eggs and two pieces of white

toast for breakfast. Not much, but I haven’t had an appetite.

The

hiking wasn’t strenuous, but at this altitude, I still plodded. At times I

walked alone, at other times with Lhakpa,

the 29-year-old sherpa assigned

to accompany me as I tried to catch up with our group (I’m two days behind

everyone due to food poisoning). He carried my 44 lb. rucksack as well as his

own on his back the entire time. After two days, I finally caught up with

everyone in Dingbouche. Tashi, the lead sherpa, hugged me! I made it! “Many people get sick on

these treks,” he shared, “but not many recover to continue the

trek.” I felt instantly better hearing that.

Saturday April 8, 2017

“Snow mountains, more than sea or sky, serve as

a mirror to one’s own true being, utterly still, utterly clear, a void…”

Joe Trasker and Chris Bonington, Savage Arena

|

| Climbers Memorial |

Our group of nine climbers set out and the

walk was a switchback uphill for a while, which we all took slowly, with Ryan

in the lead. No one spoke for a long time. Up and up… the mountains were

stunning, the road dusty.

Eventually

after two hours we came to the climbers’ memorial. These are cairns of stone,

erected in memory of those lost on Sagarmatha (Everest).

First I saw Rob Hall’s, which was plain; Hall was the guide portrayed in the

2015 movie “Everest.” Then Scott Fisher’s, which was colorful with

prayer flags and writing (he was also portrayed in the movie). Prayer flags

flapped in the wind above. The wind was cutting-cold and borderline

uncomfortable.

After

paying our respects, we walked on, this time more downhill and soon came to a

lunch spot. I only had half of bowl of soup and one piece of toast.

Now

came the hard part: over an hour of plodding, up and up. Dust, wind, no air.

Yak caravans broke up the monotony now and then. One step at a time. Everyone

slowed to a crawl. There were a lot of people now on the trail. After an hour

we came to flatter surfaces with low scrub, big round boulders. The walking was

easier. We walked for another hour to hour and a half, and came to Lobouche at 16,000 ft. I felt great now.

No headaches. We crashed at the picnic tables inside, and had tea.

I

watched Maria eat a Snickers bar and suddenly felt really well.

Jess took out chocolate covered pomegranates and I devoured a bunch.

Tomorrow

we will hike and stop at Gorak Shep

at 17,000 feet. Monday we will arrive at base camp.

Sunday April 9, 2017

“… Charles Dickens, crossing the Atlantic in

1842, described his cabin as an ‘utterly impractical, thoroughly hopeless and

profoundly preposterous box.’” The Lost City of Z

It’s 7:30 pm and I’m already in my sleeping

bag. It’s. so. cold. My fingers are numb. But I paid

$3.50 for a little bowl of hot water and I washed my face and hands and it felt

excellent. I knelt before the bowl as though I worshiped it! It’s a tiny little

room, just plywood.

Yet looking out the window,

I see stunning views of the Himalaya at night. The mountains are stark against

a clear, cold night. I can see the Big Dipper at my window, bright and

magnificent.

We

started at Lobouche, hiked some

steep hills at times, switchbacks, some rough terrain. Yaks continued to pass

us, jangling their cow bells. Jess has severe sinus problems. We stopped along

the way to rest. A slow, easy trek about three hours. We arrived at Gorak Shep today at 11 am. It was a

surprisingly dirty place. We had lunch and then the group climbed a local hill

to see Everest, but I opted to stay behind and rest. When Chris and Rob

returned, even they looked cold and spent.

Monday April 10, 2017

“This is at the bottom the only courage that is

demanded of us: to have the courage for the most strange, the most singular and

the most inexplicable that we may encounter.” Rainer Maria Rilke

I’m relaxing in my clean, spacious tent at

Everest base camp finally! We’ve all had lunch and it’s 2 pm. Everyone’s pretty

tired, but a good tired, from hard work.

We

were up at 6 am after a wonderful night’s sleep despite the cold in the tiny,

plywood room. The room was freezing overnight! Everyone seems tired today, or

in their own little world. It was

windy and cold, and we started to ascend. It was a long morning. A two-hour

hike turned into a three-hour hike because we fell in behind a yak caravan and

we couldn’t pass. It was too dangerous as the trail was so narrow and high.

Large rocks bordered the path, keeping us from pitching over mountainsides. So

we plodded: the yaks, the sherpas,

our guides and me.

My

fingers, grasping trekking poles, went numb from the cold. Luckily my toes were

warm and my core was fine, thanks to five layers of warmth. Rocks littered the

path; this was hard work. I could hardly lift my eyes to see the peaks anymore.

The wind kicked up and knocked me down onto a rock at one point. I didn’t know

it then but I had already lost four pounds.

At

17,500 feet, we’re at 50% oxygen levels. My breathing was labored as I tried to

suck in as much oxygen as I could. Jess was feeling ill, and lagged behind. A

sherpa and Jess’s husband Chris helped her all the way to base camp.

|

| First glimpse of Everest |

As

I trudged along, I looked up at one point and unexpectedly saw the tip of

Everest. Before it were triangular mountains with snow caps, looking almost

cheery, like ski slopes. Then behind them, a menacing black triangle jutted in

the middle—Everest—with a shroud of white mist swirling about it, like a black

sorcerer’s cap surrounded by ghostly conjurings.

That

is Chris Bombardier’s prize:

Everest. Despite the strong wind and my frozen hands, I laid down my

poles, unclipped my backpack

and struggled to remove my digital SLR camera to capture this. I thought, It

looks like a minister, wrapped in his black robe, protected by his minions with

their blue capes with white fur tops. And at their feet, and below me, was a

valley with moraines and glaciers…. A violent geological upheaval that happened

thousands of years ago. Rocks, boulders, ice blocks, all jumbled together in

chaotic form, a testament to the birth of the Himalaya and all the earthquakes

and avalanches there since.

At last

from up on our ridge, I could see below tiny yellow tents in the distance, in a

valley of blue ice. Base camp! The camp grew closer, the tents more in focus.

The terrain became even more difficult to manage. I squeezed through some tight

rocks and wondered how on earth the yaks with their burdens squeezed through

these same places?

Descending

into the valley, I finally hit level ground and saw the big rock decorated with

prayer flags and a sign: “Everest base camp 2017.” Ryan and the group were

there and Ryan offered a high five. He asked how I was feeling—how was my head?

I told him I felt great. We waited for Jess.

|

| Everest base camp! |

It

was still another 20 minutes to our camp. The group pulled away again and I

actually got lost and confused at base camp. Where was our tent? So many tents

and groups all staked out their camps. I felt like a penguin chick who lost its

mother and faced a mob of others who were not terribly sympathetic. Finally I

saw Chris and Jess and waited to walk with them.

Camp

is nice! Once there, we met in the mess tent, relaxing and having tea. Some

euphoria, and lots of fatigue. Leif confided he felt so much emotion at being

back. Eventually the sherpas served

a wonderful lunch. The table was covered with a cheery tablecloth, with

colorful plastic flowers that added a touch of home. There was tea, coffee and

cocoa set out with biscuits. My personal tent even had a welcome mat in front

of it!

Our

camp sits right at the foot of the famous Khumbu ice

fall; I couldn’t believe that I was gazing on this natural wonder, this thing

of legends. I knew from all my readings of Everest and all the documentaries

and movies I’ve seen, that this was the start of the Everest summit hike. The

climbers must navigate this ravaged glacier, which has crumbled into a morass

of massive ice blocks, collapsed seracs and

endlessly deep crevasses. The climbers begin here and then can move on to

higher camps and eventually the summit. The ice fall would take them over six

hours to navigate; they’ll need to use ropes and up to 12 aluminum ladders over

the crevasses and up the sides of some glacier blocks. It’s a frightening

labyrinth. And here it was, first thing I could see when I unzipped my tent

door!

Tuesday April 11, 2017

|

| The magnificent Khumbu ice fall from my tent! |

I set up my tent yesterday, straightened out

everything for the next three days. It’s so cold! When the sun

goes down, wow. So I put in my sleeping bags my clean clothes for tomorrow. Tashi gave me a hot water bottle for my

bag, which was heavenly. I slept at 6:30 pm and woke up at 11:14 pm

absolutely freezing! It must have been 15° or lower. I could see my

breath. It’s hard to describe how the cold is; you take it personally that it

is trying to hurt you. I was awake till past 3:30 am. I heard avalanches, the

slow crashing of a mountainside, a roar that makes you wait and hold your

breath. Sometimes the wind barreled in, making it colder. My breath condensed

on my sleeping bag ridge near my mouth, forming little sheathes of ice. I

hardly drank any water all night, maybe a cupful as it was in the bag with me,

tied up in a dry bag. If the water spilled and my sleeping bag got wet, I’d be

in real trouble.

I

drifted back to sleep a bit, and finally the morning came. I could only sit up

and pull on clean clothes, then get back into the safety of my sleeping bag. I

had to dash out of it to grab throat lozenges in the outer portion of the tent,

then Advil, then back under the covers. After 30 minutes, I got the courage to

pull on fleece pants. If you told me two hours later I’d be showering

in a tent, outside, I would have called you crazy! But I did it.

The

sun started warming everything. At 8 am I ventured out for tea in the mess

tent. I had to climb over rocks and down makeshift steps to get to the mess

tent. I was actually feeling pretty good by then. Just light-headed from lack

of hydration, sleep and food. But the others had headaches too.

|

| In front of camp: monstrous seracs |

The

shower was simple and good. Solar-heated hot water in a bag suspended overhead

inside a tent. I felt refreshed, clean and renewed. At 10:30 am we met all

the sherpas, and I realized how

much work they had done in the previous two weeks before our arrival to set up

this camp.

Wednesday, April 12, 2017

I went to bed last night at 6:30 pm, taking no meds this time. I drifted in and out of

sleep, and despite temps dropping to a bone-chilling 1°, I slept beautifully.

In

the morning, the sun came out and the temperature shot to about 40°. And I was

so relaxed, after a 12 hour sleep, that I started enjoying everything. Our camp

sits in a valley hemmed by stunning mountains, and strange glacial forms.

Before us, the Khumbu ice fall

waited.

After

breakfast was a gear check for Chris and the other climbers and then Tashi set up the aluminum ladder, and had

everyone cross it, including me!

The

weather was warm, the food good, the company nice. That day I stayed up till

8:30 pm and then went to bed. I had a bizarre experience in the night. I

woke up at 11 pm, absolutely gasping for air. It felt like someone was

strangling me. This happened throughout the night till about 3:30 am, when I

bolted out of the bag, into the grim, subfreezing air to grab a Diamox. I

had not taken any in 24 hours. Without it, I felt I was being asphyxiated. Kat,

one of the climbers, told me the next morning that this was “Cheyne-Stokes” syndrome. As we

sleep the brain registers it is not getting enough oxygen, and so causes a

reaction that wakes us up, feeling like we are drowning, so we gulp in more

air.

Thursday April 13, 2017

“… as a mountaineer the essence of life is in

the struggle, the contest against great odds…” Joe Tasker and Chris Bonington, Savage Arena

I’m sitting in the noisy but very warm and

stuffy, rustic dining room in Lobouche tea

house, where Jess, Lhakpa and

I stopped around 6 pm, after the return-from-base-camp trek from hell, unable

to proceed any further. We were lucky enough to get one room, the last one

left, and we claimed it, even though it was like sleeping in a meat locker

overnight.

|

Priorities: the sherpas erect

a small stupa for prayer |

I

awoke this morning, our last day at base camp, cold and shivering. I’d be

leaving base camp, and after a three-day trek, be back in Lukla. Jess has been absolutely suffering with

a massive sinus infection and constant headaches for four days. By 10 am, I

noticed three huge cloud formations in the direction we would be leaving. The

sun, always so welcome and warming the air by 30 degrees, disappeared this

morning and a damp cold settled in. I was concerned; we had a five-hour hike

ahead of us through rough terrain in very cold weather with bad weather

apparently on the way and a sick hiker. Jess and I should have started our journey right after breakfast, when

it was warmest and when it gave us time. But we started out at 1:15, very late.

Why?

Well, there was the puja ceremony,

a necessary ritual to bless the climbers. The llama came at 10 am, sat on the

ground in front of the makeshift stupa and

chanted. Safety concerns overrode my desire to participate or celebrate. I

snapped photos but also ducked into the mess tent to escape the cold. It was

hard to enjoy the ceremony with this trek hanging over my head.

The

ceremony lasted two hours. Eating, incense, chanting, rice throwing. Then came

Sherpa singing and then dancing, which was fun. At the foot of the Khumbu ice fall we all did the Sherpa

dance, stamping our feet, arms about one another in a circle.

|

| Chris Bombardier practicing on ladder |

After

lunch, I said my goodbyes to the climbers: Maria and Frederick, Leif and Tona, Kat and Meretta. We hugged good bye

and I blew kisses, with Maria tearing up. I was amazed at this daring group of

people from Norway, Sweden and France, all hardcore mountaineers.

But my

favorite mountaineer was outside: Chris

and Jess had a hard time parting. Both were sobbing, with Rob catching it all

on film. I hugged Tashi good

bye and said good bye to all the sherpas.

Then we were off. My parting look at Chris was of him sitting on the ground at

the edge of the little glacial pool, mournfully looking away, tears in his

eyes, with Rob filming him. He and Jess would not see one another for 5

weeks or more.

|

| The puja: to bless the climbers |

The

trek was really tough. We forged uphill, at a snail’s pace. Rocks were

everywhere, endangering our steps. It took 45 minutes to one hour just to exit

base camp and get on the trail leading out, which went up and down continually.

The ascents are hard due to the altitude; just a few steps up leaves you

gasping for air, your quads burned out. You wait to replenish the oxygen in

your system and try again. We passed climbers coming in, trekkers, yaks and

mules and porters. Jess was hurting still. Eventually we walked two hours in

this dusty, rocky, geological mess, at times not able to see anything—not even

other trekkers—except rocks, boulders, mountains, grey and old, solid and

unforgiving. We came at last to Gorak Shep.

We stopped only for tea; the place was so dirty and cold even we didn’t want to

stay, tired as we felt. As soon as we sat down at a table in the dining room,

Jess curled up in a ball to sleep. I wasn’t at my best either, coughing

constantly and cold.

The trail was a wild, rocky mess. I was bundled up with six layers on top, but just hiking pants

below, a hat, buff and great hood. My feet were fine. My fingers went numb as I

was wearing only glove liners and not my ski gloves, which were in the rucksack. My nose

ran constantly, into the buff. I steamed up my glasses, so I couldn’t see where

I was going. Now and then I paused to see my surroundings: moraines, ice hoodoos, piles and piles of rocks of all

sizes and types—some as big as houses. The stunning, massive Himalaya, which

now looked dark and foreboding. The cloud cover was extremely low, as if to

blind and oppress the mountains. The wind blew at a clip, chilling us. I kept

thinking, It could always be worse, so be glad. Just put one foot in

front of the other. This day will eventually end. You know that much.

The

wind picked up and it started to snow. Jess was getting worse. Lhakpa had to support her and she slumped

to the ground whenever we stopped. Other times she coughed so much she

moaned. Lhakpa held her

head.

What

if this gets worse? The cold air, the lack of nourishment, the constant

walking. We asked a Sherpa who passed us about hiring a donkey. But the idea of

Jess on a donkey for another two days was absurd. This was a tourist road; we

had options.

What

about a helicopter? I asked Lhakpa and

he explained the costs. We made it somehow, the next 30-60 minutes to Lobouche, where there was literally one room

left at the tea house.

We

got an unheated room with three beds. Lhakpa fussed

with Jess, taking excellent care of her. He put her in the bed, in a room so

cold we could see our breaths. He brought her hot soup and a thermos of hot

water to sip through the night. He also brought a hot water bottle, which Jess

clutched to her as a mother would a baby. I finally told Jess I was ordering a

helicopter. The chopper would come at 6 am, and it would take 7 minutes, not

two days, to get to Lukla!

Friday April 14, 2017

The night was long and fitful, sleeping in a sub-freezing

room. Jess awoke at 3:30 am, coughing and moaning. Lhakpa was right there to offer hot water, and to compress

her head, which helped. After about 15 minutes, he went back to bed, singing.

The next day I asked what he was singing, and he told me, “A prayer.” What an

endearing young man. Jess and I tipped him well as he offered to us compassion

and help that cannot be feigned or bought.

|

| Rescue! |

The

helicopter arrived around 6:20 am. We were easily up, dressed, packed. Skipping

breakfast or even hot tea, we walked out to the landing site, just the top of a

slight hill, and waited. The red rescue Fishtail helicopter thwacked its way to

us and we boarded. Truly about 10 minutes later we had bypassed all the rugged

trails, the dust, the yaks, the tea houses, and flew over this mountainous and

beautiful country, and landed in Lukla,

high on a hill, the starting point of our trek two weeks ago. The chopper

landed right next to the mountain top clinic, and we went inside. A kindly

British doctor was there, who checked Jess over, gave her prescriptions for

antibiotics, pain killers and decongestant, and in about an hour, a second

helicopter came to take us to Kathmandu.

It

was here in Lukla that we said

good-bye to Lhakpa, who cared for

me for two straight days after my food poisoning, and who cared for Jess on her

difficult journey. We would truly miss him. We could express our appreciation

in words and in a huge tip, worth two months salary for him. His life is hard.

What would he do when trekking season is over? “Work on our family farm,” he

said. Maybe pick up odd jobs for trekkers or visitors. He has no steady income

and like most in Nepal, is poor.

By 10 am we had flown back to Kathmandu, and were in our hotel.

What a contrast: clean, hot water, soft beds. It seemed surreal.

And I was

besieged by “climber’s guilt.” I could enjoy for the next few days

all the comforts and luxuries of a modern hotel while Chris and the climbers

slept every night in that bitter cold, had to climb up to Everest, camp by

camp, further into the thin air. But that’s what separates mountaineers from

the rest of us. They are focused, impervious to so much hardship, welcome it in

fact, push themselves to the extreme.

Chris Bombardier

is poised to make history as the first person with hemophilia to summit Everest. In

fact, he already has made history as the first to attempt it. With what

I have seen of his fortitude and courage, he will make it. I’m honored to have

spent the days on the road with him, seeing him in action, sharing a little of

the hardships they faced and will face, to understand the sacrifices they make,

which are huge. He had asked me if we could do a base camp trek with others

with hemophilia, and I replied count me out! But after two days, yeah. I can do

it. I learned a lot about myself and how I respond to this hostile environment.

I knew more about it and myself. I can apply that and push the envelope

further. Yes, I would do it again.

|

| www.saveonelife.net |

And it was a

wonderful World Hemophilia Day in Kathmandu with the Nepal Hemophilia Society

where we praised Chris for doing this, because he highlights the disparity in

treatment between countries like the US and countries like Nepal. I reminded

the crowd on April 17 that the first summit of Mt. Everest was not Sir Edmund

Hillary of New Zealand, it was Hillary and Tenzing Norgay, a sherpa from

Nepal. Together they conquered the tallest mountain on earth. Together we will

conquer the disparity in hemophilia care one day.

Thanks again to Chris, and to Octapharma for full sponsorship of this climb. Follow Chris at Adventures of a Hemophiliac on Facebook. Please consider helping those in Nepal at Save One Life!

|

| Hard good-bye: Chris and Jess Bombardier |

|

Laurie Kelley and Jessica Bombardier:

cleaned up and ready for home! |

If you’ve been following my blogs and Facebook postings, you’ll know that we have history in the making: Chris Bombardier is poised to be the first person with hemophilia to attempt to summit Mt. Everest, the tallest mountain in the world. Risky? Beyond words. I’ve read all the books, about Everest and many other legendary mountain climbs; I’ve read about the history of mountain climbing. I’ve done some mountain climbing and most recently accompanied Chris on the nine-day trek to base camp. Not a Sunday stroll! It’s cold, hostile, and indescribably beautiful.

If you’ve been following my blogs and Facebook postings, you’ll know that we have history in the making: Chris Bombardier is poised to be the first person with hemophilia to attempt to summit Mt. Everest, the tallest mountain in the world. Risky? Beyond words. I’ve read all the books, about Everest and many other legendary mountain climbs; I’ve read about the history of mountain climbing. I’ve done some mountain climbing and most recently accompanied Chris on the nine-day trek to base camp. Not a Sunday stroll! It’s cold, hostile, and indescribably beautiful.

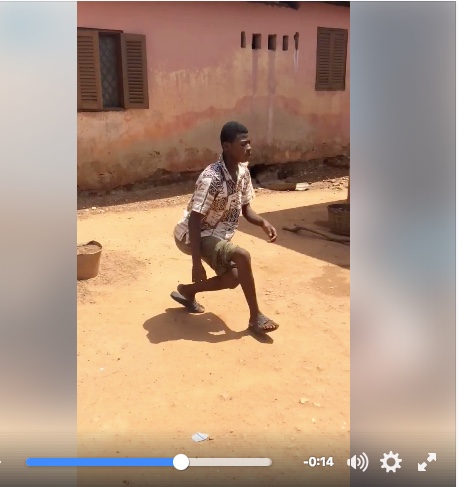

As he risks so much, please honor his climb and efforts by contributing to Save One Life, Inc. Go to my Facebook page to see a video of Amos, of Ghana, a young man I sponsor, who walks bent over, suffering from permanent joint damage.

As he risks so much, please honor his climb and efforts by contributing to Save One Life, Inc. Go to my Facebook page to see a video of Amos, of Ghana, a young man I sponsor, who walks bent over, suffering from permanent joint damage.