The Amazing Dr. Mütter: Father of US Plastic Surgery

“But what sustains the physician, in the stillness of night, in the chamber of pestilence, in the reeking hut of the sick beggar—in the cell of the maniac? A moral courage, which bids him die rather than desert his charge—a God, who tells him that “a faithful shepherd must give his life for the flock!” Thomas Dent Mütter

Last week I took a brief trip to Philadelphia, the birthplace of modern medicine in the United States. I am fascinated by the history of medicine—perhaps because I had a son with hemophilia in 1987, although I can recall desperately wanting to be a veterinarian as a child. Nowadays, I just read everything I can about medicine through the ages. For this trip in particular, I wanted to revisit The Mütter Museum, an odd and eclectic collection of anatomical and medical anomalies, kind of a Ripley’s Believe It or Not for medical students.

But you don’t have to be a medical student to learn a lot from this astounding collection.

And while it is Bleeding Disorders Awareness Month, and we are all sharing information about bleeding disorders in the US, I think it is good for us all to appreciate the humble roots of all medicine, and especially appreciate the remarkable legacy given to us by Thomas Mütter, who was born this week, March 9 in 1811 in Richmond, Virginia. Sadly, his mother, father and younger brother died by the time he was seven. His maternal grandmother took him in, but then she died not long after. He was then raised by a wealthy friend of his father, who put him in a boarding school. Thomas, now lacking any family and suffering bouts of colic, decided to become a doctor. And what a doctor he would become.

In the 1800s, Paris was the epicenter of medical innovation, and Mütter would eventually study there, and witness poverty and suffering. Even still, life was harsh and brief then. Children were abandoned; more than sixteen thousand children were wards of the Hôpital des Enfants-Trouvés, and four thousand of those would never live to adulthood. He saw how open-minded the French were in their approach to medicine. He studied under legendary physicians, especially

Guillaume Dupuytren, of Paris’s largest hospital, the Hôtel-Dieu, the city’s, who altered the course of surgery. Dupuytren performed les opérations plastiques—plastic surgery. “Plastique” doesn’t mean plastic, but flexible. This surgery hoped to reconstruct injuries using the patient’s own body, such as tissue, skin, or bone, to heal.

At age 21, Mütter returned to Philadelphia, where there were (and still are!) two superb medical colleges—the University of Pennsylvania and Jefferson Medical College. In fact the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine became the first and only medical school in the thirteen American colonies in fall of 1765. Surgery at this time was still crude. There was no anesthesia, and the best surgeons were usually the fastest. Mütter was ambidextrousness, and could do twice the work in half the time, it was said. Public sanitation was nonexistent, and Philly, like most big cities, was hit hard with epidemics. In 1793, yellow fever struck; in 1832, a cholera epidemic hit. Without electricity, surgeries were performed in natural light or by candlelight.

Mütter was such a notable surgeon, so talented, that he was awarded the chair of surgery at Jefferson College. He was their youngest and least-tested professor.

He appeared to be beloved by his students; his lectures were fascinating. At a time when lecturing was very one-sided—students listening and professor talking—Mütter was first US professor to introduce a more informal style of teaching, asking questions and engaging in dialogue with his students. Mütter’s reputation was also enhanced by his habit of bringing specimens to class—preserved body parts, often in jars. These would form the basis of his museum.

He had other firsts: introducing a new type of plastic surgery that is still today used, called the Mütter flap. Keeping patients overnight in recovery beds, instead of being sent home the day of surgery in horse-drawn, unsanitary carriages with wooden wheels. Suspecting that physicians introduced germs to patients during their physical exams as they did not wash in between patients—sepsis, which would not be confirmed for years later. Becoming the first surgeon in Philadelphia to administer anesthesia for surgery, even though his peers did not trust the newfangled chemical. He struggled for anesthesia to be adopted by the medical community to end unnecessary human suffering—proving himself to be a hero to patients.

And with all his accomplishments, it was perhaps his compassion and tenderness towards his patients that made him different from everyone else. From students to peers to superiors, everyone noted Mütter’s gentle manner, listening skills and time spent comforting the suffering. Perhaps because he himself had suffered so much in life.

“’Brilliant as Dr. Mütter was in his didactic teachings,’ one of his students later wrote, ‘he surpassed himself in the clinical arena.’ Mütter’s methodical nature and utter focus before, during, and after the surgery was unprecedented—as was the amount of empathy and kindness he displayed for those under his care. Furthermore, Mütter was known for putting ‘considerable emphasis’ on the care and attention he paid to patients prior to performing the operation. He would not only develop a bond with the patient via gentle, consistent communication, but would also physically as well as mentally prepare them.

“Because of this care, Mütter’s work and reputation rose above that of his contemporaries. He even treated a man who suffered horribly from elephantiasis and, immediately afterward, took up a collection for the man, reminding the students that compassion for someone like this does not stop at the operating room door.”•

His legacy is vast. For example, he inspired people like Edward Robinson Squibb, who was inspired to find a way to standardize ether, and provide doctors and surgeons with standardized chemicals for their work. His advocacy later led to the creation of the US FDA.

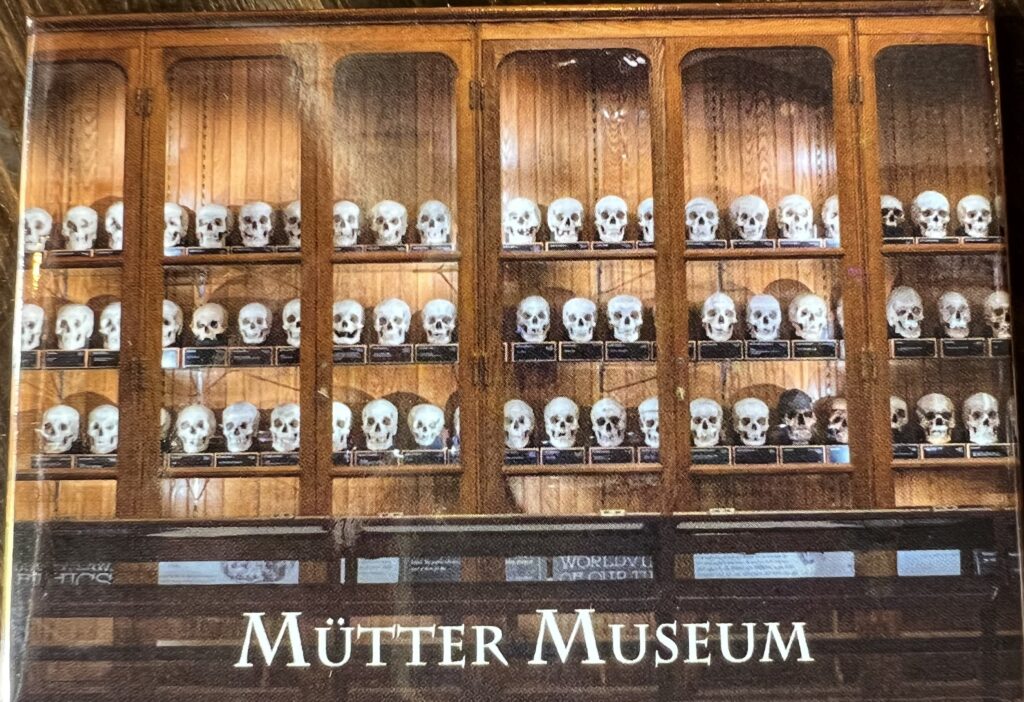

And then there is the Mütter Museum. Mütter had seen jars of fetuses and deformities in anatomy in Paris, labeled “MONSTER.” He brought a feeling of humanity to these unfortunates. By keeping them on display, he taught his students compassion for those who suffer. At first Jefferson College refused to create such a museum, but Mütter knew his time on earth was short, and pushed. Finally, in December of 1858, an agreement approving the Mütter Museum was, at long last, legally recognized. Dr. Thomas Dent Mütter died a mere three months later, at age 47.

Try to visit the Museum if you can; Philadelphia is a city filled with history, of our nation—and our medicine.

“This world is no place of rest. It is no place of rest, I repeat, but for effort. Steady, continuous undeviating effort. Our work should never be done, and it is the daydream of ignorance to look forward to that as a happy time, when we shall wish for nothing more, and have nothing more to accomplish.” Thomas Dent Mütter

- Excerpted from Dr. Mutter’s Marvels: A True Tale of Intrigue and Innovation at the Dawn of Modern Medicine by Cristin O’Keefe Aptowicz