Layoffs and Life Cycles

Boston had some bad news last week: Wayfair, a Boston-based national e-retailer of household goods, is laying off another 1,650 jobs, or 13% of its workforce. The CEO admits they are “bloated,” and had a hiring frenzy during Covid, when people stayed home and engaged in home repair and redesigning. It’s not the only major employer to do this: Google and Amazon have also laid off many workers, and even the classic magazine Sports Illustrated is facing massive layoffs and even bankruptcy.

Even the bleeding disorders community is facing its own layoff challenges, as Hemophilia Federation of America (HFA) laid off nine staff members, in a bid to make its financial structure more sound. This came as a shock to the community, and Facebook lit up with questions and even condemnation. Emotions run high in this community, as do expectations.

HFA cites the every-changing landscape of bleeding disorders, which primarily means funding. And funding is directly related to market share of different manufacturers, because most of HFA’s money, like NHF’s, like almost everyone in bleeding disorders, comes from manufacturers.

It wasn’t always like this. During the HIV crisis of the 1980s and 1990s, “pharma” did not donate as much as specialty pharmacies, which were on the rise in power and influence. HFA itself was founded by patients in direct response to the perceived lack of community representation and poor decision-making of the National Hemophilia Foundation (NHF), which the community believed let them down. It was believed that receiving funding from pharma influenced NHF’s decision-making on whether patients should continue to take injections of commercial factor VIII, when it was suspected of having HIV.

HFA refused money from pharma then, and only took money from specialty pharmacies. HFA was a grass-roots organization that seemed to truly put patients first. As time went on, particularly with the rise of Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs), and as we predicted in a series of articles in PEN, which you can read here, insurers resumed their influence over access to product, and larger specialty pharmacies acquired and merged with smaller ones. The pool of donors was consolidating. Many of the small specialty pharmacies were founded and run by people with hemophilia.

Our community went from dozens of specialty pharmacies devoted solely to providing factor, to where we ended up now: Only a handful, with PBMs dominating distribution, and insurers dictating products and access to care.

All the more reason to have advocacy groups like HFA. Unfortunately, funding was consolidating too, and with insurers dictating benefits, specialty pharmacies had little influence over and subsequently little reason to woo patients. PBMs continued to dominate, and smaller specialty pharmacies continued to be absorbed… and disappear.

HFA now had to rely on pharma money, which is where we stand today.

And it’s true: the landscape is changing. We have an overcrowded field of products (download our factor chart), and a limited consumer group for these products. Top dogs with the highest market share will feel little need to contribute funds when their products are favored by both patients and prescribers.

But there is also the natural life-cycle of a nonprofit at play. We now have two national organization and dozens of state organizations: all to service several tens of thousands of people. Is it overkill? Products are state-of-the-art, safe, effective and abundant. What role will the nonprofits play? Do they need to consolidate to survive, just as specialty pharmacies did?

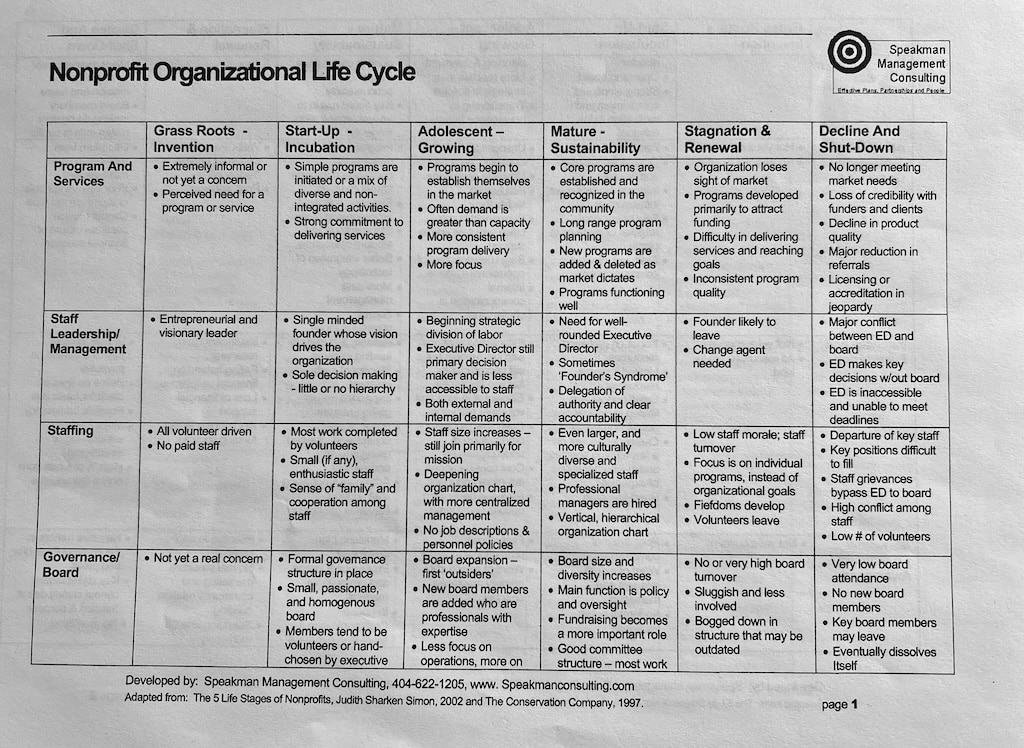

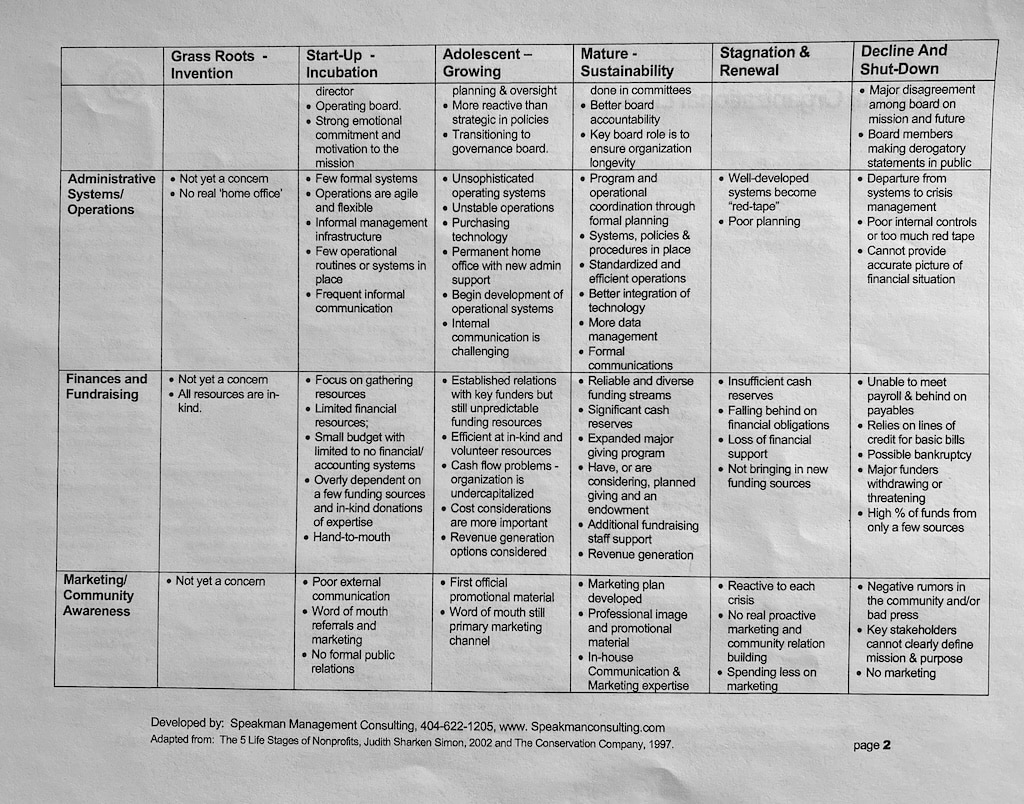

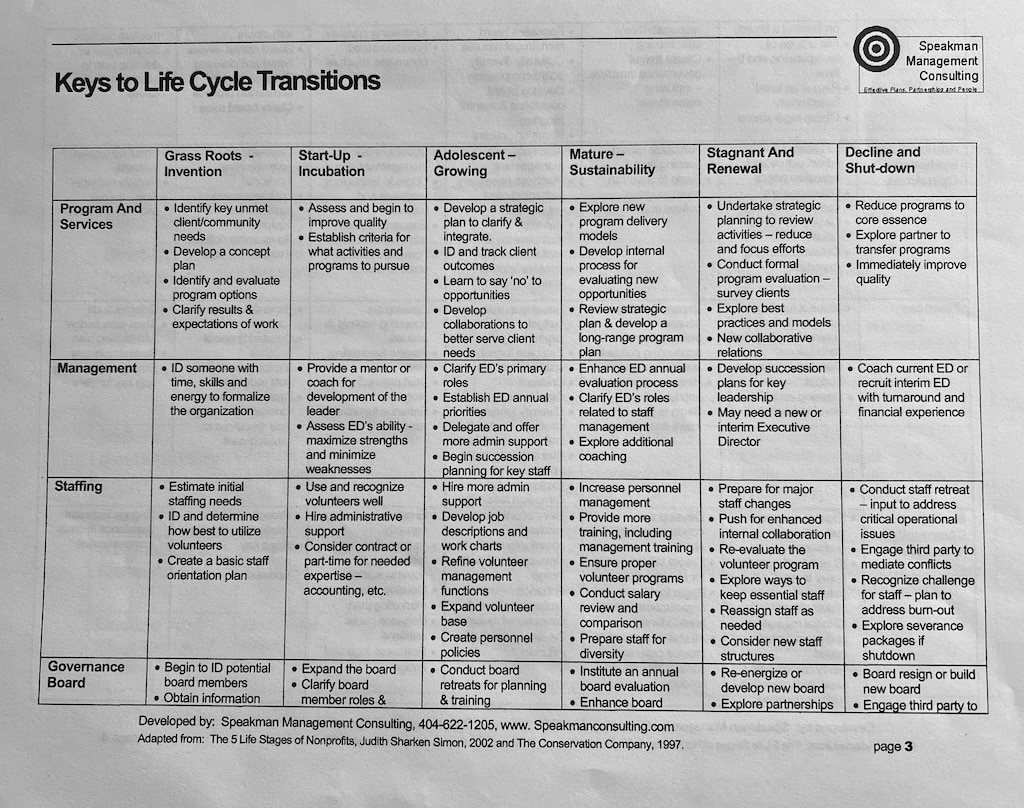

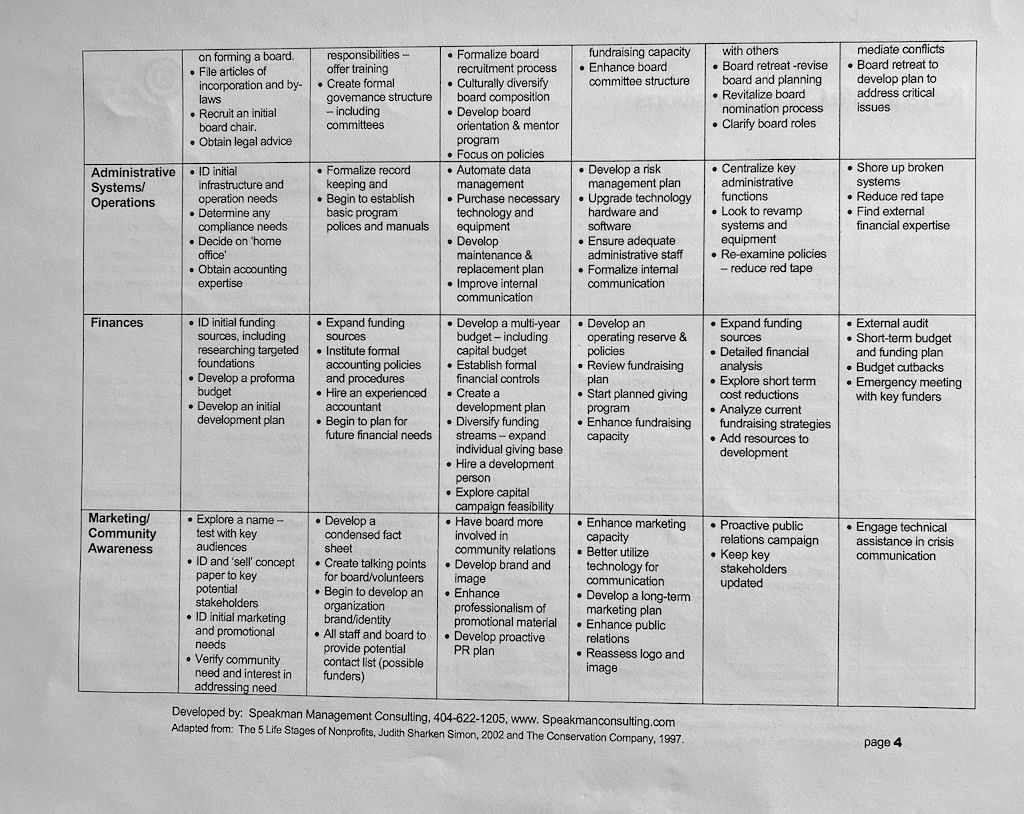

I was given this nonprofit life-cycle chart (below) by an executive director, which shows that nonprofits, like businesses, have life cycles. Read it carefully. Do we find ourselves in the “Stagnation & Renewal Stage”? Restructuring might be the first tactic to resolve this, so perhaps HFA has taken the right first step. We should try to understand and not condemn at this point.

A restructuring does, however, signal a scary time for those who fought so hard to bring HFA to life, keep it breathing, and keep it growing. In survival, the “fittest” are not the most funded or best even, but those that adapt to a changing environment. We need to know what is happening in the environment—here, funding sources, manufacturers, patient needs—and whether the current structure can survive. The board and CEO have decided it cannot. So it is attempting to adapt.

I wish it success, and pray it continues, as I am fond of HFA, proud of its achievements and know the community needs it, in any form.