Rockin’ the Pain

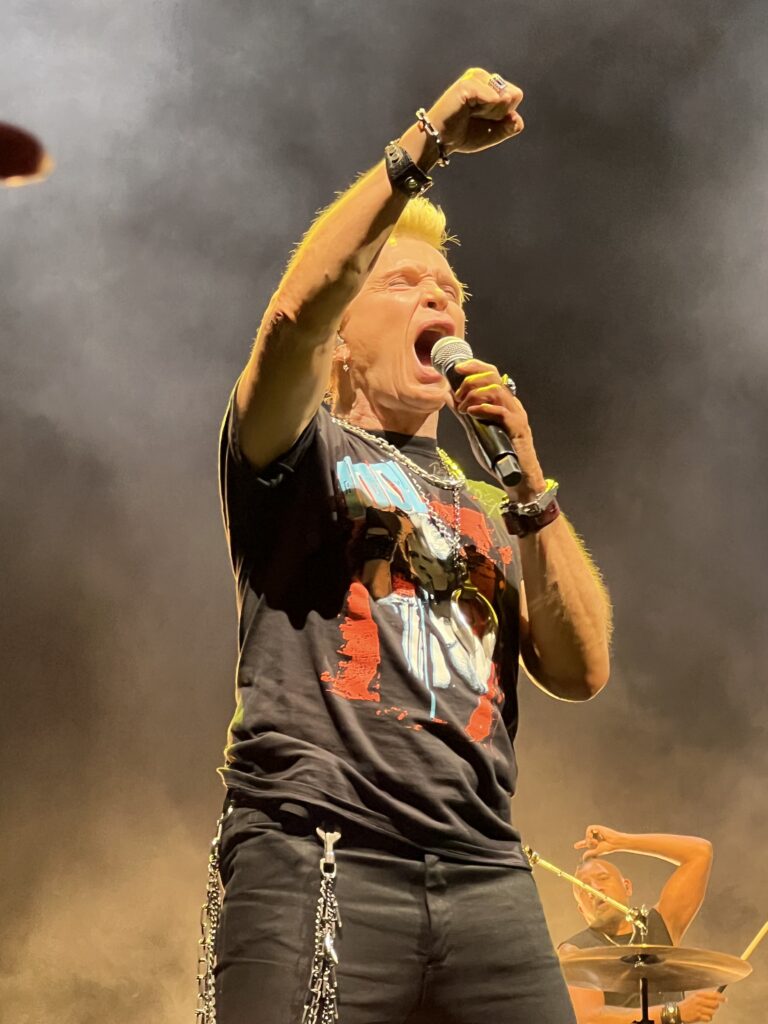

Last night we saw a great concert: Billy Idol, and his famed guitarist Steve Stevens. Energetic, pumped up, still looking and sounding great, Billy Idol used to thrill us, now he amazes us. Despite a devastating motorcycle accident in 1990, in which he almost lost his leg and endured seven operations, he made a come back. (Tidbit: he was supposed to play the part of the New Terminator in T2: Judgment Day, but he was not able to walk. The part went to Robert Patrick).

While recuperating, and for many years later, he reflected on his real problem: drug addiction. And for someone who was now in chronic pain, this was doubly worrisome.

As I watched him rock and cavort on stage, I marveled at his physique and passion. He put on a great show. And to top it off, he is age 70. Seventy! It’s incredible where he was, how he endured and what he does now.

Meanwhile, I was the one in pain, row C, seat 21, with an unrelenting back spasm, that sent thudding pain across my lower back, while compressing nerves that shot electrical currents down my left glute. At times I couldn’t even watch the show, as I was trying desperately to find a standing or sitting position to ease the back pain. Nothing worked.

Chronic pain like this makes me empathize so much with our bleeding disorder community members. Older patients endured the most incredible pain, as untreated bleeds compressed nerves in joints and muscles. The damage those bleeds leave behind is arthropathy, or arthritis, which does not go away. t was easy for our patients to become addicted to painkillers.

Chronic pain requires a different treatment approach than acute pain. Pain medications to treat both acute and chronic pain are often divided into three groups:

1. Non-opioids, including acetaminophen and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

2. Opioids (narcotics), including hydrocodone and morphine.

3. Adjuvant analgesics, a loose term for many medications, including some antidepressants and anticonvulsants, originally used to treat conditions other than pain.

Unlike acute pain, chronic pain often doesn’t respond to OTC medications. Even highdose,prescription-only NSAIDs may not reduce the pain; and when used for extended periods, they pose a significant risk of bleeding complications and other serious side effects. So for moderate to severe chronic pain, opioids (narcotics such as morphine and codeine) are the drugs of choice. But the big fear is addiction.

With that in mind, therapies to pursue are non-medication therapy, called Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM). These are any adjunct therapy used along with conventional medicine. Here are some of the most common:

Relaxation Therapy. Biofeedback Training

Behavioral Modification. Stress Management Training

Hypnotherapy. Counseling

Acupuncture. Therapeutic Massage

Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS)

Chiropractic manipulation. Ultrasound

As with any procedure, always consult your hemophilia treatment center (HTC) for more information and advice.

I recall attending a Metallica concert in 2018, where the opening act joked that the rockers used to hang out backstage, drinking or smoking before a show. Now they are backstage getting massages and doing yoga, due to their age!

For me, my issues are age-related somewhat and activity-related mostly. Doing too much, too often. I have compressed discs and arthritis in the back. I need to step up my yoga, heating-pad, chiro visits and massages. But this morning, I relented and popped a prednisone tablet for this period of inflammation.

I’m not sure what Billy Idol does, but whatever it is, it’s working!

Don’t take pain lying down: if the 60s, 70s and 80s rockers can get by at their age and with their antics, you can get some relief, in some way too!