Kenya’s Maasai: Do They Have Hemophilia?

I’ve been back almost two weeks now from my African adventure, and the Kilimanjaro climb, and my toes are still healing! One of the great privileges I find when I travel to Africa is the chance to meet and chat with the Maasai. The Maasai are an ethnic group of semi-nomadic people who live in Kenya and northern Tanzania. They are among the best known of African ethnic groups (which the Kenyans call tribes). You can’t miss them with their beautiful red cloth (indeed, “Maasai” means red), elaborate beads, braids, spears and daggers. They tend to be tall, reed-thin and love to jump super high in ceremonial dances. They live out in the savanna, in circular villages (which you can see from an airplane!) called bomas. Their culture is based on cattle: cattle is their currency, their food, their livelihood, their everything. They speak Maa, and many can also speak Kiswahili and English. There are about 840,000 Maasai in Kenya. Quite a few visited the Keekorok Lodge, where we stayed for three days after our rigorous climb.

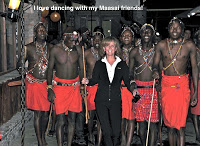

Indeed, as soon as I stepped off the bus that brought us to the Lodge after a quick 5-minute ride from the dirt airstrip, I saw a Maasai waiting at the front lobby to greet us. It was Daniel! I met him last year during my visit. We had a wonderful chat while he was welcoming the other guests. We also caught up later that evening, after the Maasai came to the Lodge in full force and sang, or rather chanted and whooped, around the dinner table! The Lodge pays them to come and entertain the guests. They sing, do their walking/chanting, and then go outside to do the leaping that really is their trademark. They all try to outdo one another with their leaping. I learned that whoever jumps the highest attracts the most girls!

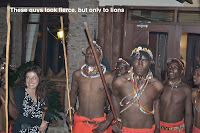

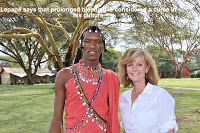

They can look very ferocious, and indeed, one of their rites of passage is to kill a lion. Around age 18 or so they are expected to become warriors, and to do this they must have several things done. One is to kill a lion with a spear. When I mentioned to Daniel and Lepapa, another Maasai I met last year, that we are taught to fear lions, they both looked at each other and smiled knowingly. “There’s nothing to fear from a lion,” Lepapa said. “Now Cape Buffalo, that’s an animal we fear.”

Another rite of passage is circumcision. This is also usually done at age 17, as part of a group. The young warrior-to-be is expected to not make a sound when then circumcision is made. This is how he shows his bravery. With me in this discussion was Julie Winton, a nurse with BioRx, who had made the Kili climb. We both naturally wanted to know if there was any prolonged bleeding. With a population of 840,000, there is a good chance that the Maasai have someone with hemophilia. In fact, I recall in a previous visit to Kenya, maybe in 2001, I met a Maasai who had hemophilia, though he lived in the city and not in a boma.

As fierce as the Maasai are, they are really gentle, very soft-spoken people. Quietly, Lepapa said, yes, there are some who bleed excessively. What is the reaction of the elders, and those conducting the circumcision?

“They would say it’s a curse,” Lepapa acknowledged.

Julie explained about blood clotting, and that this wasn’t a curse. The two young men were very interested but explained the elders tend to be more superstitious. Obviously Daniel and Lepapa are more educated and have more experience with the world than perhaps some of their elders. Still, Julie and I thought how fascinating it would be to find a Maasai with hemophilia, and to try to bring care to them.

A huge challenge for many of the Maasai is that they live far into the savannah, and not near any major town. There is often not even a medical clinic for routine problems like broken bones. A clinic is something Daniel’s village needs, he noted.

It was a very interesting meeting of cultures; the young warriors (although Lepapa has admitted he didn’t kill his lion yet, and “..really have to in the next two months..”) were curious about our work with hemophilia, and Daniel’s eyes popped wide when he saw Julie’s iPad. He has seen them before, but hers had pictures of cows. Julie lives on a cattle ranch! The topic switched from hemophilia in Maasai circumcision rituals, to artificial insemination and calving.

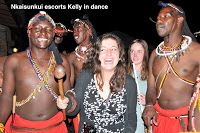

That night we celebrated our climb by dancing with the Maasai.

Great Movies, Which Showcase the Maasaiq

Mountains of the Moon

About Irishman Richard Burton (Patrick Bergin) and Englishman John Hanning Speake’s (Iain Glen) exploration of the African interior via Tanzania in the mid-1800s to find the source of the Nile, and how their friendship unraveled as a result. Incredible story. Stylish, action-packed, thought-provoking, and true. 1990

The Ghost and the Darkness

True story: In the 1800s, Irishman John Patterson (Val Kilmer) is chosen to build a bridge for the new railroad in Kenya. Work is delayed when two lions break all natural instincts and become serial man-eaters. Nicknamed the “Ghost” and the “Darkness” by the African workers, everyone lives in fear of their reckless killing. Up to 100 were killed, and Patterson seeks to kill them himself, but soon enlists the help of a lone hunter (Michael Douglas) who brings in the Maasais. Great ending, not to miss! Lush, beautiful film, score by Ennio Morricone, but adventure packed and intense, like an African “Jaws.” 1996

At 19,340 feet, Kilimanjaro is the highest mountain on the African continent and the largest freestanding mountain in the world. And guess what? I am going there in August! I’m actually going to hike it and attempt the summit. Why? Not just because it’s there, but as a fundraiser for Save One Life.

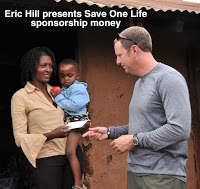

At 19,340 feet, Kilimanjaro is the highest mountain on the African continent and the largest freestanding mountain in the world. And guess what? I am going there in August! I’m actually going to hike it and attempt the summit. Why? Not just because it’s there, but as a fundraiser for Save One Life. The climb is the brainchild of Eric Hill, president of BioRx, a homecare company, and a sponsor of two kids with hemophilia. Last year he, an employee, and a person with hemophilia, Jeff Salantai, climbed Mt. Rainier. That was a highly technical climb, meaning they had equipment, ropes and crampons. Thankfully, Kilimanjaro is not a technical climb, but it’s no walk in the park! With a team of ten, we will trek for 4 days, hopefully summit on the 5th, and then come all the way downhill in one long day.

The climb is the brainchild of Eric Hill, president of BioRx, a homecare company, and a sponsor of two kids with hemophilia. Last year he, an employee, and a person with hemophilia, Jeff Salantai, climbed Mt. Rainier. That was a highly technical climb, meaning they had equipment, ropes and crampons. Thankfully, Kilimanjaro is not a technical climb, but it’s no walk in the park! With a team of ten, we will trek for 4 days, hopefully summit on the 5th, and then come all the way downhill in one long day.