Durgapur: Civility in Poverty

On Tuesday November 12, Usha and I took a 6 hour train from Kolkata (Calcutta) to Durgapur, one of my favorite stops. Why? I don’t know.

Perhaps it’s just the smallness of the city that charms me. It’s poor but colorful,

manageable. I was only there for a day three years ago, but I feel I recognize it and am at home here. Isn’t that odd?

The train ride was long, and Usha and I chatted a good portion of it. They serve delicious masala tea, which makes it bearable. But while we are used to our jumbo size coffee cups, tea or coffee is served only in dainty little dixie cup sizes. I am chronically caffeine-deprived. When we arrive in Durgapur, I look up from my seat and Ajoy Roy is already there, grabbing my luggage. It feels like no time has passed since I was there

three years ago. Ajoy has no personal connection to hemophilia, other than his friend, Subhajit Banerjee, who has hemophilia and runs the chapter, yet he dedicates all his free time to helping our boys. Subhajit and I have been acquainted for 15 years, mostly through the internet and at World

Federation of Hemophilia meetings. Cars were arranged and we go straight to the hotel, not far away. Getting all our luggage and ourselves into the small cars is tricky but the Indians are resourceful and clever and somehow, no matter how much we bring, it all fits. This is perhaps the nicest of the hotels we stay in for our entire trip. The air is hot but not humid; sunny skies, busy city, with autorickshaws, bicycles, cars and cows bustling about with the speed of a mad video game (well, except for the plodding but sacred cows).

Usha and I wash the train from our hands and feet, have lunch together, taking our time, sort the toys and factor and head to the large and clean treatment center. Durgapur is lucky to have a whole center dedicated to hemophilia. The patients are gathered and have waited so long and calmly for our arrival. Many recognize me and I them. We sit at a table at the head of the room, smiling at the families. Subhajit, Ajoy and other members of their team hover about, ensuring everything goes correctly. They give lovely speeches welcoming us, and present gifts; I present a check for $500. Then we ask to meet the beneficiaries, especiailly the recipients of our new scholarship fund

The Save One Life scholarship fund is unprecedented in hemophilia. I got the idea for it during my travels, when assessing the needs of patients. Over and over, the young men asked if there was any financial help to get them through college. Education is a lifeline in countries like India; without a degree, you do not stand much of a chance of getting good work. The young men are hungry for education, a degree and work; with these, they can buy their own medicine and one day support their families. The eldest son in an Indian family will be expected to care for not only his parents but any dependent sibling, like unmarried sisters.

One of the most interesting young men we met is Sukdev. He’s taking a two-year computer

One of the most interesting young men we met is Sukdev. He’s taking a two-year computercourse at the ITI (Industrial Training Institute). His father is a cook in a small town; they are very poor. He’s a great singer, according to everyone present, and Sukdev bows his head, sheepishly smiling. He had a CNS bleed en route to camp when he was younger. Camp was

his first exposure to life outside his little village, population 400. He

learned about head bleed symptoms from chapter, so when he got a bleed, he knew

what was happening. Subhajit and Ajoy are proud of this outcome. It took him over four hours to get to this meeting. I feel guilty; we give him some money for transportation.

All five young men we meet with are doing well and look good. They have special needs: two need laptops, which we pledge we will try to get for them. After these interviews, we meet with all the families again. The hunger in their eyes—for money, factor, help—is penetrating. We finally meet each one, snap photos, distribute toothbrushes (a gift from the Hemophilia Foundation of North Carolina) and puzzles and other donated toys. One mother becomes agitated and speaks out, tears in her eyes. Her son cannot walk. The staff talk to her to calm her, and some might think she was exploiting our visit, but I tell Usha I don’t blame her. You get no where by being quiet and this is her moment, with a foreign visitor. A big discussion ensues about the child, who observes quietly. The mother wants factor, help.

drawn carts, cars, bicycles and occasionally a massive water buffalo. The streets are fringed

with vendor shops, which sell everything from vegetables to tires. The sun sets until it is pretty much dark when we reach the thatched home of Sheikh Rajiv. We have to trek behind some other village homes in the dark, through went grass, to arrive at his home. Subhajit has a flashlight and shines the way, warning me not to fall off the path and into the adjoining field. I wonder if there are snakes slithering around.

mud, with a hay roof; the one room is only 12×12 for four people. There is

electricity, but no refrigerator or any convenience of any type. Living here

is primitive. The father works in a rice shop. His office closes at 10 pm and

he bikes back from Durgapur over the very rough, dangerous roads, about 10

miles, which takes over one hour. Every day he does this. And he has a child

with hemophilia to consider. We sit on the bed, which takes up half the room,

and the family is excited and nervous. We ask questions, present gifts to the

two children, and their mother brings in a tray with drinks and wonderful Indian

desserts. I could write a blog just on Indian desserts. They are indescribably

delicious. Despite having already eaten, we taste some of the desserts. First,

because they are great! Second, this is a huge deal to this family. To have

international guests come to their home, and to serve them. It would be the

height of rudeness not to accept something. Despite their poverty, Sheikh is

doing well and looks great. He is well cared for by the society. When we leave,

the village turns out to gawk and then wave us on with good wishes. They love

having their photo taken.

Tuhin Das lives just down the street. Indeed, Sheikh’s father comes with us to show us where he lives. This house is slightly bigger with a front entry–but we are still talking rustic and small. Still it’s big enough for a bed, a table, some chairs and a bookcase. The father is a strikingly handsome man, tall and lean with chiseled features. I sought to compare him to some movie star, maybe Clint Eastwood. The inside décor is a riot of color and knick knacks, giving the room a busy but warm feeling. A little plastic table

with plastic chairs is set, and the father ceremoniously and carefully brings

in a tray with more sweets and soft drinks. It hits me how polite and classy

these two families are. I have been in countless homes throughout the world,

including homes of millionaires and homes of the destitute. I have found the

greatest level of graciousness in the homes of the poor. They shower us with

welcomes, with humble sincerity, and put their guests first. It’s always a

lesson in civility on how to treat guests. The father sets our plates with the

flair of a well trained waiter.

vegetables. He earns about $1 a day. He does have a fridge, which the first

father eyes lustily. We discuss what would help each family further, and the

Sheikh’s father would really like a fridge. Imagine if that were the number one

item on your wish list? We told him we can get that for him and in fact, I give

Usha the money and tell her to get him one tomorrow. The mother can use the

fridge to store factor, but also to “rent” out some shelves and earn a little

extra money.

byes, and head back on the bumpy road, out of the rural village, back through

the size of either home.

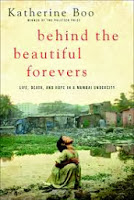

Great Book I Just Read

Behind the Beautiful Forevers by Katherine Boo [Kindle]

Boo spent several years embedded in a Mumbai, India slum to record the true stories of life as a slumdweller in India. Trash sorters, street vendors, teachers, prostitutes… the slum has a delicate economic and social balance that is easily tipped when disaster stikes, as when one of the inhabitants sets herself on fire, and another family is accused. The book centers on this dramatic and true case, which serves to hihglight the daily struggle of indiviudal families, how they deal with the corrupt police, sway politicians and try to survive. A masterpiece in international development literature. Four/five stars.

Boo spent several years embedded in a Mumbai, India slum to record the true stories of life as a slumdweller in India. Trash sorters, street vendors, teachers, prostitutes… the slum has a delicate economic and social balance that is easily tipped when disaster stikes, as when one of the inhabitants sets herself on fire, and another family is accused. The book centers on this dramatic and true case, which serves to hihglight the daily struggle of indiviudal families, how they deal with the corrupt police, sway politicians and try to survive. A masterpiece in international development literature. Four/five stars.