Kilimanjaro: Days 4-6

We must embrace pain and burn it as fuel for our journey. —Miyazawa Kenji

Tuesday August 9, 2011

Facts: More than 20,000 tourists attempt to climb Kilimanjaro every year. Six out of 10 will not finish. About 10 people die each year during the climb, usually from high-altitude sickness.

It is cold now, about 40 degrees. We awake in our tents in the Barranco camp, which sits in a valley, at 6 am as “Young” Frank and Ellie bring us much-appreciated hot tea. It’s hard to complain when they are up before us, wear less than we do, tote our gear the same rough path we do, earn a few dollars a day and always serve with a smile. There’s no chance of washing up in this winter weather so we change into whatever clean clothes we can find, brush our teeth, spitting into the bushes, and then quickly get to the mess tent. We have this getting ready thing down to a sort-of science.

After breakfast, Jonas unzips the mess tent door flap and walks in, with Jacob in tow. Today we will walk about seven hours to base camp, Jonas tells us in his solemn baritone. seven hours. Jacob always stands a bit behind him, on his toes, grinning like the Cheshire cat, enjoying the look on our faces. We’ll arrive around 3 pm, have dinner at 6, go to bed and try to sleep a bit, then get awoken at 10:30 pm, pack and gear up, and strike out for the summit around 11:30 pm. We are nervous, and excited.

First we must scale the 800-foot Barranco Wall, a steep fortress of volcanic rock at 12,959 feet that requires what’s known as a “scramble,” hand over hand climbing, and provides some scary moments. It takes about an hour and a half to do this, and while we grunt and sweat, porters seem to zoom by us with their heavy loads. Truly amazing to watch. We respectfully step aside when they pass.

Once we scale this wall, we again descend, knocking small rocks and gravel down below us. Soon we are on steadier footing. As we pass through the Karanga Valley, the walk is quiet, as if we are lost in our own thoughts through this alpine desert which continues to enchant me. Rocks abound, creating a barren, lunar landscape in the middle of lush Africa. At first the rocks were lava, black and pitted remnants of an ancient volcanic explosion. They are huge and massive, all around us. Then, they appear smaller and smaller, until they look like little cannonballs scattered about, as if some African battle had long since been waged. Finally, about five hours into the rigorous hike, the rocks turn to sedimentary rocks, Jonas tells me, which are flat, stacked one on each other like pancakes. A dozen people walking on this new pathway make the rocks crack, sounding like stone chimes with each step. It’s an odd feeling, as nine Americans shuffle on the dusty trail quietly in this eerie atmosphere now, dust kicking up around our boots constantly. Our vision is now limited by a mist or cloud that has moved in. We trudge forward like explorers in a new land, unsure of where we are headed. We keep our heads down to watch our footing, and also because we can’t see much other than the person in front of us. Looking down, I see a sprig of pretty yellow flowers, like a surprise greeting. The asteraceae. The strange juxtaposition makes me want to take a photo, but I remember ruefully that Jonas has my camera. Later, as I look through my photos for the day, I see that he took the very same shot that I wanted!

Dust is our enemy today. It is everywhere: in our nasal passages, our ears, hair, hands, and fingernails. Our boots are embedded in dust; our pants sift dust. Kelly has had a cough the whole trip and the dust must affect her terribly but she never complains. The rocks and our slow pace affect Jeff’s ankles; while he also never complains, he asks if he can go ahead of the group at a faster pace, which will actually make it easier on his ankles. The angle is really hurting him. The guides grant permission and he and Frank take off. I tell you, these are tough hombres with me.

We will be on the trail today for seven hours. I slog behind Brittney now, the last, with Jonas bringing up the rear. Since he has become such a good photographer, I let him keep my camera. At 3 pm we finally arrive at base camp, exhausted. As the porters have arrived ahead of us, as usual, our tent awaits us and I sink to its floor. I’m sure we are all thinking the same thoughts: this is it. No turning back. We are going to attack Kilimanjaro in a few hours!

It is freezing. It must be about 15 degrees. The tent offers a little shelter, and we quickly unpack and pack our gear and clothing, stock up on Gu gel and Cliff bars, Advil and electrolytes. I am thinking rapidly, fueled by adrenaline. Even if we sleep a few hours, the summit will take about seven hours, bringing us to morning. That means we will have had only a few hours sleep in 24 hours, while all the time pushing our bodies to the extreme in zero degree summit weather. I focus on packing instead.

Dinner is a tense affair as we are all excited. We speak about what we feel: some feel nauseated, some think we can do it, some don’t want to think about it. We eat a little and then head off to our tents. Keeping warm is all about layers, so I plot out how I will dress: thermal base layer, top and bottom; flannel pajama bottoms (nothing could be warmer), and another thermal top; fleece top with a hood and ski pants next; my EMS super-warm black jacket and rain pants for bottoms. Topped by a down ski parka. A balaclava for my head and my fleece hood, and the ski parka hood and I am good to go!

We strip off the layers for now, bring some of them into our sleeping bags to keep them warm and settle into our bags. My bag is rated for zero degree weather and even if I only wore a t-shirt and shorts I am as warm as toast. It’s amazing how light it is and how much it protects me from the cold. I stick in my ear plugs as the porters clean up, pop a melatonin and eventually drift off to sleep for a while.

I wake up at 10:00 pm, hot, and it’s about 5 degrees out. My excellent sleeping bag? Eastern Mountain Sports Mountain Light 0°. I throw it off me, worried about sweating. Once you sweat and get wet, you could be in serious trouble with the cold. No sense in sleeping anymore as young Frank will be by soon to wake us up. Now I am nervous. The mountain looms before us, and we must go. I start by putting on the layers, including head, feet and gloves. Oh, forgot the head and foot warmers! I unlace my shoes and insert the foot warmers, and get a set of hand warmers going. Once I am done, I stumble to the mess tent, where Jonas, ever solemn, waits to tell us what to expect tonight.

We have a light meal of porridge and toast. Some in our crew are feeling nauseated, mostly from nerves, and cannot eat. Jacob comes in to “motivate” us which means “Get out of the tent, everyone! Get out of the tent!” He knows there are many teams wanting to climb tonight, and he doesn’t want to get stuck waiting behind a line of climbers. We switch on our head lamps and go. Bundled up, geared up, we are ready to climb Mt. Kilimanjaro, the highest peak in Africa. We will attempt 4,000 feet in zero degree weather all night long.

It is biting cold; the stars overhead are brilliant. The air is still and calm. We fall into our formation, with me in the rear, as usual. Jonas is behind me, Frank ever in front. We carry only our backpacks but there are more porters with us, I suppose in case someone falls ill. Altitude sickness is a true concern. Its symptoms are a headache which gets progressively worse, like a migraine; nausea; and chest fluids. So far, we are all good. No one has really had any symptoms. Once in a great while one of us will feel a headache but it goes away.

We trudge, one foot in front of the other; it’s 11:45 pm. We should only concentrate on one foot, one step at a time. I don’t recall exactly when I start feeling the profound effects of oxygen deprivation. After one hour of climbing, we stop and rest, eat Gu gel or have water. The air is dry and thin and hydration is the key to success. Our noses are runny, and will continue all night long, and for days afterwards, we will all have sore, raw, peeling noses. It’s hard for us to navigate our own backpacks, so the porters are there to help us. The minute I fumble with my mitten, just even to check the time, Joseph is close at hand to help. I marvel that their clothes are not as thick as mine; their shoes not as good as mine. Yet, they are ready to help in a split second, whatever our needs. On we go.

Wednesday August 10, 2011

It’s 2 am, and I am stripped of every ounce of energy. My mind is clear, no nausea, but my legs feel as if someone wrung them out as you would a towel. I feel as though my muscles just shriveled into nothing. There is no power that can make me put one foot in front of the other. My breathing is very labored: “Uh…” I exhale, “Huh!” I inhale loudly. We stop again, collapsing onto our trekking poles. The porters and guides are all fine; they are all acclimated and feel none of the effects that we do. They wait patiently while we try to get more breath to get oxygen to our bodies. We are all feeling something.

I am surprised to get a hot cup of tea from Joseph! Where did it come from? The tea revives me. When we stop, it is a relief as I can catch my breath, but then a deadly cold sets in, and so we must keep moving.

It is a surreal experience. I look overhead and have never seen so many stars, so clearly, so close to earth. I feel like I could reach up and touch them, if I wasn’t so oxygen starved. The moon shines brightly, illuminating a large stretch of rock that we are climbing. Below us are clouds! It is beautiful, primitive, captivating. Time to go, Jacob pushes us on.

We hear singing. Jonas has started a song in the clear and frosty night air, and the porters all join in, chanting. It’s in Kiswahili, so we don’t know what the song is about, but it is great. The rhythm helps us find a stride, and the singing is motivating. On my right, Jonas walks alone, singing, overseeing all the climbers. On my left, several porters silhouetted in the near dark, outlined by the moon, climb swinging side to side, like dancing, swaying to the music, right leg out, left leg out. I feel like we are dancing our way to the summit. Overhead, stars burst the night sky like fireworks. I see Orion low on the horizon, kissing the clouds below us. Directly before me, my fellow climbers, all in a row. We walk in formation, right, left, right, left, feeling like a chain-gang, for we cannot leave now. We’re in too deep. Chanting, we move slowly up the mountain, stepping up rocks, hoisting ourselves with our trekking poles.

Leaning heavily on my poles, I place one foot in front of the other. I realize I need to stop again. Then again. Then again. I cannot get 25 footsteps without stopping to gasp for air. Can I go back? How can I do this ridiculous feat? Twice I ask Jacob if I can go back; I don’t think I can make it, and I don’t want to keep holding the group back. There are more climbing teams below us, and Jacob doesn’t want us to get clogged on the mountain trails. Yes, I want to go back. What a disappointment! I scaled the mountain for two hours, but I cannot in my wildest dreams imagine another four hours of my legs burning and collapsing under me. I simply cannot will them to go on. How can you make your body move when you are completely depleted of any reserves?

Joseph waits patiently for a decision. He will do whatever the guides decide. He is like my personal servant, ready to help me remove my gloves, which I did at one point, in ten degree weather! The minute I started searching for the Camelback tube, fumbling with my mittens, Joseph is there to guide the tube to my lips. I never felt cold. The layering worked well: I only felt some chill and slight numbness in my toes but all else is perfectly warm.

I’m not the only one hurting. Brittney looks vacant, staring; Julie, who was in the front, vomits, resumes her hike, and then vomits again. Jacob moves her to the rear. The next thing I know, Jonas has Jacob put me in the lead. Why the lead? This is the worst idea! I am so slow and will slow everyone down, and the entire set of climbers below me… such is my confused thinking. Joseph is now ahead of me, and I plod along at a snail’s pace, losing all sense of where my teammates are. Maybe they are ahead of me after all? All I know is that it is deathly cold, the stars are beautiful, and only Joseph and I exist in this strange, surreal world. One step. Another step. Another step.

I rest again. When will this end? I see that the group is behind me a distance, and I actually gained ground. This encourages me and I start up again, feeling that I am doing better than I realized. Jonas starts singing again, and I recognize the tune “How Great Thou Art,” my favorite Christian tune, sung in Kiswahili. I love that song because it praises God’s hand in nature, and it’s appropriate as we are surrounded by some of the most beautiful nature in the world. This compels me to focus and push on. The next song is another beautiful Christian hymn, one my grandmother used to sing, “Rock of Ages.” Also appropriate. I wonder if Jonas actually does have a sense of humor after all.

By 3 am, I am so dead, I want to lie down and be left behind. I know now why people who are caught in winter storms, like those on Everest in 1996, want to just lie down and fall asleep in the snow and die. It’s so inviting, and my legs are once again bereft of any kind of reserves. They feel hollow, worthless. My trainer, Dan French, told me during training that when my legs were depleted and exhausted from exercising, then my body would start using other parts, like abs or the back, and this is where my previous back spasms came from. I started thinking about this as my legs are now depleted. Sure enough, my back starts aching viciously, and then my abs. Three more hours of this? Impossible.

I am no longer put in front. I guess I am in trouble now. I would later learn that the singing is a way to help motivate climbers—it works. Putting the slowest in the front is also a psychological trick to get the climber motivated. When they are “last,” they feel worthless, a burden, hopeless. True, true, true. And that worked, for a while. The only things not working are my legs.

Jonas now steps in to help me. Jacob is sent to take care of Julie. I am given Red Bull at 3 am in zero degree weather. I sip it but oh, horrible stuff. I feel like a child refusing its milk, making faces. “You need energy for your muscles,” Jonas tells me. He continues to tell me about how it will quickly get energy into my system. Joseph helps me get up, and this time Jonas locks my left arm tightly with his right arm and paces me; he pulls on my arm and I follow. This is good and bad. It works; I move up the mountain. But it means I am not going to my sleeping bag any time soon.

“Do you have a headache?” Jonas asks dispassionately. No. “Do you have nausea?” No. “How is your chest?” I’m fine; no coughing or fluid buildup. “You’ll be okay,” he states matter-of-factly as he squeezes my arm tightly. I consider lying next time he asks.

Up we go. My life is now reduced to a few things: one foot in front of the other; hydration; labored and noisy breathing; leaning on this arm of iron. I need to focus on something other than the burning and constant pain in my legs. I recall that President Theodore Roosevelt would recite his favorite poetry when he was in trouble on his expedition to Brazil, after his presidency. He traveled to the River of Doubt, which was not completely charted on the world map. He did finish the expedition and put what is now the Roosevelt River on the map, but almost died in the process. While suffering from malaria, he recited the poem Kubla Khan over and over. So I started to recite my favorite childhood poetry, and realized that I don’t recall a lot of poetry. My favorites were from Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book so I started reciting it in my brain. Now Chil the Kite bring home the night that Mang the bat sets free. The herds are shut in byre and hut and loosed till dawn are we…

I am now stopping to gulp air every 25 steps. At this rate I will summit sometime next week. Why doesn’t Jonas let me go down? Please, I beg. He once again coolly and without the slightest emotion asks: Do you have a headache? Are you nauseated? How is your chest?

Lie, lie, I tell myself. But I don’t. I confess I am fine; I don’t have altitude sickness.

“You can make it,” he replies calmly, amid the struggling climbers, and me, slumped on his arm.

Where have I heard those words before? I realize that this climbing Kilimanjaro is a lot like childbirth. In fact, worse than childbirth, and having had three kids, I know what I am talking about. You are in extreme pain; you are exhausted. The night is endless. Your vision has been reduced to tunnel vision. You can focus on nothing but the pain. People are telling you to push (on). But in the back of your head, you know that there is a glorious outcome waiting for you. You feel alone, though you know you are surrounded by caring people. You want to scream at those same people when they tell you you’re okay; you will make it; you’re doing well. And worst of all, you asked for this!

Jonas and I walk about as slow as two humans can walk, up the steep incline, energy melting away with every step. I stumble along the endless switchbacks; I fall; I trip over every rock and trekking pole. We take breaks; I ask him to sing again because it really does help. I can’t recall if he ever did.

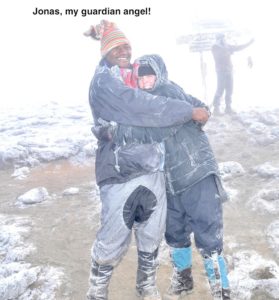

Things get so bad when we pause that I start sinking to my knees. Jonas supports me by giving me a hug, allowing me to lean into him, and pats my back and with no emotion says, “You can do this, Laurie. You can do this.” He doesn’t want me to stop walking, knowing that cold will overtake me. The next rest time, I am hanging on to him with what strength I have, saying, “I’m trying” or “Ok.” I apologize a lot to him for all my inadequacies as a human being, for wasting his time, for trying to think I could do this. He doesn’t really answer these ramblings. Probably he has heard all these confessions before from every climber, and then some.

It’s a macabre dance: plod, plod, plod, hug, hug, hug, head buried in his parka, struggling to breathe in air that is 50% less oxygen than sea level. Joseph stands ready to help with water, and at one point, to help drag me. When they allow me to sit down, which isn’t often, my eyes close right away. “No sleeping,” Jonas lectures. This is absolutely taboo, but so hard to comply with. My eyes have a will of their own.

I decide that counting helps me focus and maybe I can measure my improvement? I count out loud my steps with a raspy, labored voice. I get to 25, and we must stop so I can breathe again. Eventually I get to 30 before stopping again, then 50. I am getting encouraged! Somehow we make it towards Stella Point, at 18,848 feet, where the ground gets flatter, and I actually reach 100 steps before I have to stop. It’s amazing how quickly the legs recover and get oxygen when the slightest pressure from gravity is removed. I continue to count out loud. Jonas, who seems to have no sense of humor, surprises me with a hint of one. “Laurie,” he said, “Try counting in your mind. Save your energy.” I felt half rejected and half amused. I think Jonas just made a joke at my expense.

“Only 20 minutes now to summit,” Jonas informs me. Incredible. The night that seemed so endless, so pained filled, is nearing the end? Suddenly the wind picks up and blows fiercely. The ground is covered in snow and frost, which surprises me. When did this happen? We see more people, though they move like ghosts in the blinding flurries. Yes, the end is in sight; I start to walk independently, and finally, after six and a half hours, reach Uhuru Point, the highest peak on the African continent. My teammates are there already.

I think I collapsed on a rock, my mind foggy and slow. Most everyone was okay; 14-year-old Alex had his eyes closed, slumped on a rock, and Brittney was staring blankly. They all had fluffs of snow frozen onto their eyelashes and hair. My buddy Julie made it, but she also had a dazed look on her face, as I am sure I did. So we were all accounted for. Jonas had insisted I bring my 35 mm camera, which is quite heavy, to take pictures. I wanted to bring only my Sony Lumix, to reduce weight, but Jonas insisted. You just don’t argue with Jonas. He tucked my camera in his parka the entire night. At 6:54 am, he began taking pictures in the terrible weather. We couldn’t see the sunrise or even anything further than 15 feet in front of us, which is sad because we should see a spectacular view of Tanzania from here.

It was hard to see, and hard to hear one another above the roar of the wind, and visibility was bad, but we were happy. We pulled out banners and had our photos taken at the sign that signifies the highest peak. We even had a couple of humorous moments.

After about 15 minutes we had to start down again. The wind has picked up to about 50 miles per hour, and actually pushes against us. We take shelter momentarily behind a large boulder with other climbers not in our group, and when there is a break, move on down to Stella Point.

After Stella is the part I don’t recall well. It took over six hours to summit, but seemingly a few minutes to descend to a point where the snow was gone, and we could shed our layers, and see base camp. But that’s impossible. The sun was shining high now, as if to celebrate with us our victory, and a great valley spread out before us like a welcome mat. I was still weakened by the oxygen deprivation, and Jonas retained a firm grip on my arm. Joseph was ever present to hydrate me. What I do recall is hitting sand on the mountainside, and being made to “scree-slide,” which means we skied down in the sand using our boots, digging in our heels to slow ourselves. The hike down took in reality about three hours, according to my watch. The sand slopes caused me to use different muscles, and the altitude was less, but I still needed Jonas to help steady me.

The times I tried to hike down independently, I often lost my balance or tripped. Being rather proud, I wanted to walk down but I had to admit my limitations. “You are like a baby,” Jonas said. “Let us take care of you.” And they did. Soon we caught up with the group at a large outcropping of rocks, where we stripped off a few layers and enjoyed the bright sunshine. Somehow there was mango juice for us to drink, which normally tastes rich and delicious. Now? It tasted rancid, as everything did with the effects of altitude. But with two six-foot wardens standing over me, I sat on a rock and obediently sipped the seemingly bitter juice, wondering if I could toss it over my shoulder when they were slightly distracted. They never were.

The team was excited, even in our depleted and painful state. We did it! This was the thought uppermost in our minds. We actually did it!

Barafu base camp is visible but seems like an optical illusion that keeps moving further away the closer you get to it. At last, at last, the endless night is over and blessedly, we arrive. Mary and I collapse into our sleeping bags. It’s 10 am.

For reasons unknown to me, I’m up at 11 am, ready to march again. We still have a full day’s hike ahead of us. So after lunch, the porters break down camp and we pack up our rucksacks for them to carry, slung on our backpacks and headed out. We were taking a different route home, Mweka, which proved to be amazingly simple. Just downhill, on a trail strewn with rocks and rock steps. The going was painful due to our cramped muscles and swollen toes and knees, but it was fun. Julie and I fell behind the others, as usual, but had such a great time chatting. Jonas trailed us like a bodyguard and willingly took my camera to once again take amazingly wonderful photos. The day was sunny, warm and Kilimanjaro National Park expanded to our left as we descended the mountain trail.

We finally arrived at camp around 5 pm, late. The others had arrived about 20 minutes earlier. This was a nice camp, with a registration cabin and amenities. There were many other groups present. Pine trees surrounded us and we were all deliriously happy with the results of the day. And starving! We enjoyed our dinner immensely.

Thursday August 11, 2011

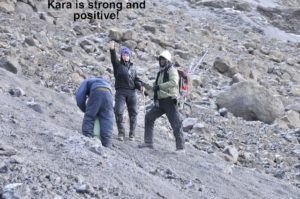

The pressure is off; we climbed Kilimanjaro! We feel some sort of euphoria which helps us to forget our swollen knees and aching muscles. I am amazed at Jeff Salantai: yes, he’s young, at 31, and incredibly fit, but he has hemophilia and just endured a major ankle operation in February. I don’t know how he managed to climb Kili! But he did, and he is limping today, but he grits his teeth, cracks a joke, makes us all smile, and carries on. Such strength! He is a poster boy for hemophilia perseverance and accomplishment!

Today we descend to the Mweta Gate, to be collected and brought back to our hotel. We have about a 3-4 hour hike downward. It’s all on trails that are very stony and rough, but well defined. And it’s downhill! That’s good news; the bad news is it will play havoc with our joints, muscles and toes. I pop some Advil to help with the swelling, have breakfast and pack up once again.

It doesn’t take long for Julie and me to get separated from the group again. We love to chat, and I like to stop to take photos. With our swollen knees, it’s easy to go slower. The scenery is beautiful in the brilliant daylight. We hike through the desert again, the sedimentary rock, then to the moorland. On our left is the broad expanse of the Kilimanjaro National Park. This way down seems so easy! We are coated in dust and there just isn’t a way to stay clean. Trailing ever behind us is our lead guide Jonas, who happily answers our many questions and begins to joke with us. Really. Julie even laid it on him: Don’t you ever smile? To which he smiled. The rest of the two hours is a walk with three friends, as we each shared more and more of ourselves. It was lovely. Who knew that Jonas was a Maasai? Did he kill a lion then, as the young warriors are expected to do? He claims he did and told us a fascinating story about it.

Nearing the end we reach the forest again, and a light rain sets in. I have no desire for rain gear. I let the rain wash away dust and refresh my skin. We start to pass locals on the trail, who know one word in English: “Chocolate?” I wish we had some but I dole out Cliff bars instead.

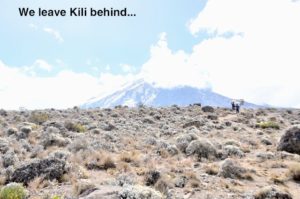

Porters race by us now, eager to finish and collect their pay. Excitement is filling the air as the trip nears its end. When we reach the gate, we are reunited with our group, and Neil is there, to welcome his daughters back! It was great to see him again! He was so very proud of his two girls.

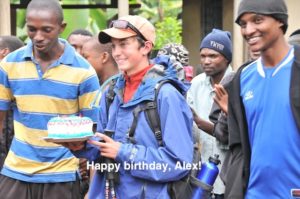

The porters and guides surprise us with a birthday party, there in the dusty parking area, surrounded by locals. Tomorrow is Alex’s 15th birthday! They sing Happy Birthday to him, and despite the long journey, they are animated and happy. They present cake and “champagne,” and Alex, despite his father’s strict southern gentlemanly upbringing, devours his piece before the rest are handed out.

My toes are gruesome. The downward walk for hours has jammed my big toes’ nails, and they are inflamed, blackened and soon, infected. They will stay this way for about two weeks. Of course, Julie immediately provides me with antibiotics. What would I do without her? (Thirty minutes after my plane lands in Boston I am off to the podiatrist to have them lanced.)

We have a 90 minute ride back to the Kibo Palace Hotel in Arusha. First, a lunch break at a local restaurant, where our three guides give us a chance to regroup and chat about the trip. The wash basin is right in the dining area, and I am ecstatic to see soap and hot water. I wash and wash but cannot believe how dirty my hands are; the water runs black. I am so excited, I go to the back of the wash line to wash them a second time!

The food is fresh and good—I eat chicken, but Frank tempts me with the strange looking beef on his plate. Tastes like, liver? Oh, it’s ox tongue! It’s all washed down by Cokes and Tusker beer. Jonas, Jacob and Frank seem happy: another mission accomplished. The ride back is quiet and I snap a photo of everyone sleeping—except Kelly Herson, who as always has a megawatt smile on her face. Back to the hotel, we shower, some of us for an hour, and become relatively human again. We invited the guides to dinner at the hotel that night at seven. We are all clean now, with fresh clothes. Jokingly, I reintroduce myself to the men I just spent six days with, as I am sure they will not recognize me without a Nike hat, hiking gear and black smudges.

Jonas presents the climbers with certificates of their climb and we leave them with some of our climbing gear as a gift, generous tips and happy memories. These guides are with Team Kilimanjaro, and I will praise them as professional, personable and efficient. I highly recommend this outfitter and its guides and porters. www.teamkilimanjaro.com

Tomorrow we head for Nairobi and then fly to the Maasai Mara for a three-day safari, our third adventure in a trip filled with adventures. As long as there is no hiking, we’re good!

Outfitters used: www.teamkilimanjaro.com Experts in climbing and summiting! Thanks to guides Jonas, Jacob, Frank and Alex, and the 40 porters who carried our supplies and equipment. Thanks to my great teammates! Thanks to all who sent their prayers and good wishes. It helped!

Thanks to all our corporate sponsors: BioRx, ASD Healthcare, Bayer Corporation, and Grifols. Thanks to the dozens of individuals who donated funds to help us reach over $60,000 for our African programs! We will be starting college scholarships, a microloan program and continue outreach to find those with bleeding disorders who suffer in silence…

Our Route up Kilimanjaro

Machame route

▪ Machame Gate (start of trek) (5718 ft/1738 m)

▪ Machame (9927 ft/3018 m)

▪ Shira (12355 ft/3756 m)

▪ Barranco (13066 ft/3972 m)

▪ Karanga (optional camp, used by 7-day climbers)

▪ Barafu (high camp before summit) (15239 ft/4633 m)

Stella: 18,848

Uhuru: 19,349

▪ Mweka (descent) (10204 ft/3102 m)

▪ Mweka Gate (end of trek) (5423 ft/1649 m)

Good Book I Just Read

Not On Our Watch: The Mission to End Genocide in Darfur and Beyond

Don Cheadle and John Prendergast 2007

Actor Don Cheadle was compelled to help end genocide after starring in Hotel Rwanda, a movie about the role one man played to save hundreds of lives during the ethnic massacres of April 1994. Together with activist and journalist Prendergast, he has started a nonprofit that seeks to educate and motivate average citizens to act. With the realization that change will only come when we link economical and political repercussions to the behaviors of sovereign nations, such as embargoes and divestiture, and not just military action, he focuses on the mass killings that occurred in and around Sudan’s Darfur region, and also inspire people to step up and speak out in an effort to generate more attention to what is happening in this part of the world. The book provides a brief history of how the Sudan incubated genocide, what role other countries have had, and what this means for the world.

The weakest part of the book is that it is an overview, not a detailed analysis. The style is difficult: Cheadle is very casual and talks a lot about himself, how he got involved, right down to detailed (and very banal) dialogues with his relatives and friends. Prendergast is quite full of himself! They flit back and forth in the first-person voice, then third-person… so you never quite know who is talking when, and the flow is interrupted. Is it a book about them, or genocide? It’s a book about two celebrities writing about genocide and their own efforts.

A lot has happened since 2007, when the book was published. The UN finally stepped in with muscle, sent an arrest warrant for the president. The UN estimates that 300,000 people have been killed in the five year Darfur conflict, which was launched against the non-Arab people of the south. And as you may know, on July 9, 2011, South Sudan has become the world’s most recent new country.

The strength of the book is its simplicity and call to action. I applaud these gentleman (Cheadle was absolutely fabulous in Hotel Rwanda, one of my favorite movies) for undertaking such a task, for motivating the public and for not just rallying but giving concrete, doable tasks to make a difference in the world. Could be used for any international activism subject. Three stars.