984

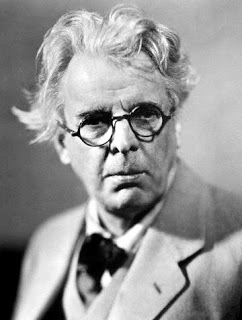

Richard Atwood, our colleague from North Carolina who researches all things in print and media hemophilia, has uncovered a great literary question: did William Butler Yeats, the Irish poet, have hemophilia?

Richard Atwood, our colleague from North Carolina who researches all things in print and media hemophilia, has uncovered a great literary question: did William Butler Yeats, the Irish poet, have hemophilia?He looks to Oliver St. John Gogarty, who published in 1963 William Butler Yeats:

A Memoir (Dublin, Republic of Ireland: The Dolmen Press. 27 pages). Richard provides a summary and comment:

A Memoir (Dublin, Republic of Ireland: The Dolmen Press. 27 pages). Richard provides a summary and comment:

Oliver St. John Gogarty, an Irish poet and physician, intended to write memoirs for nine of his famous friends. Regrettably only three were written before his death in 1957. Luckily he finished the memoir about William Butler Yeats (1865-1939), an Irish poet and dramatist. Gogarty mentions some of the accomplishments by Yeats, such as receiving the Nobel Prize and serving as a foundation Senator in the Irish Free State. He also states that Yeats disdained science while delving into the occult, mysticism, astrology, magic, seances, ghosts, and the spirit world. Gogarty praises Yeats for his poetry, especially his “intensity” of phrase by using the pouncing or surprising word. (p. 24). According to Gogarty, Yeats has the physical attributes of being 73 inches in height, being tone deaf, and having poor eyesight. Also that after undergoing the rejuvenating operations, Yeats claims to have been greatly benefited. In addition, Gogarty relates another physical condition when he and Helen Wills, a tennis champion, visit Yeats in a rented country home: “To our disappointment the maid announced that Mr. Yeats could not leave his room on account of a nosebleed. I knew that he was inclined to haemophilia. I ran up the stairs to his bedroom only to find that he had cut himself with a razor at the edge of his nostril as he was preparing to look his best.” (p. 17).

The brief memoir includes a photograph of the medallion, or plaque, of Yeats cast by T. Spicer-Simpson and a photocopy of a short poem hand-written by Sir William Watson that seems to refer to Yeats. The personal observation by a close friend, who also happens to be a physician, that Yeats is “inclined to haemophilia” is still not a medical diagnosis, though this raises serious suspicions by being from a primary source. Gogarty provides no dates for his observations, but the medical events he mentions probably occurred in 1934. The memoir may not add much to the understanding of Yeats and his poetry, but it provides an interesting personal perspective. No information is provided on the author.