Grifols, a Spanish based company that manufacturers Alphanate and Alphanine, held a one day educational conference on inhibitors for nurses in London yesterday. I was pleased to start the day with a talk on inhibitors in America: how the main struggle is finding a way to afford the treatment that is already available, given mounting pressure from payers and limited lifetime caps. Professor Alessandro Gringeri, of the University of Milan, gave an excellent comparison of ITT protocols around the world. He reminded us that ITT has been with us for 31 years, but since the first attempts, different protocols have developed. He reviewed the specifics of the Bonn, Malmo and Van Creveld Klinick protocols, and how responses to different ITT are either patient related or treatment related. ITT does not work with all patients, particularly those with mild hemophilia.

Dr. Sylvia von Mackensen is a psychologist at the University Hospital Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, and gave a presentation on Quality of Life Studies: measurements, outcomes and expectations. This is an important subject for inhibitor patients, who suffer a great loss of QoL when by passing agents or ITT are not always effective.

My colleague Becky Berkowitz, RN from the HTC in Las Vegas, Nevada, spoke about nursing in the US. Becky has a unique position working in an enormous state with a small population, and a lean HTC staff: her efforts to visit the native Americans and advocate for their treatment held the audience’s rapt attention.

The rest of the afternoon held presentations by Dr. Mauricio Alvarez-Reyes of Grifols, nurse Allyson Hague of Manchester Children’s Hospital, nurse Kate Khair of Great Ormond Street Hospital and Vicky Vidler, nurse consultant of Sheffield Children’s Hospital. It was a wonderful event, full of information and diverse speakers.

After the program, I took a tour of Great Ormond Street Hospital with Kate Khair, Virginia Kraus (Grifols), Becky Berkowitz, and Mark McDonnell, UK Manager (Grifols). It’s a major HTC, with over 450 pediatric patients, with a beautiful ward. I had always heard of this famous hospital and it was a pleasure to see it from inside.

This has been productive week: I was also able to visit on Tuesday the Haemophilia Society, which I believe was one of the first hemophilia society in the world. Chris James is the relatively new executive director, and he graciously allotted me 3 hours to tell me about their programs and population. We also spoke about sharing my company’s free resources with his members. They have excellent programs and in many ways are one step ahead of many other organizations in terms of programs for inhibitor patients.

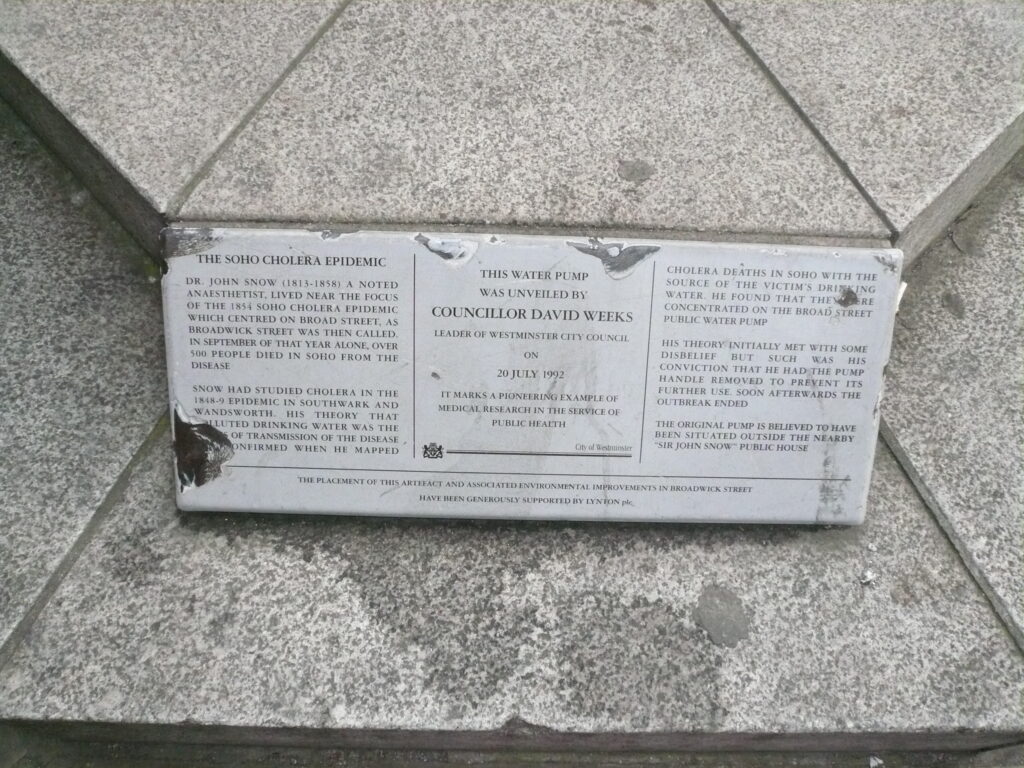

Last of all, I saw on Monday an historic site: the Broad Street Pump, the epicenter of the devastating 1854 cholera epidemic of London. This important landmark represents the beginning of modern public health. It was here that a contaminated well led to hundreds dying within one week, and caused English physician Dr. John Snow to buck conventional medical thinking, which thought it was miasma–bad air– that caused the outbreak (this was before germ theory). By using a scientific method and putting himself at great risk, Snow interviewed an entire neighborhood, noting where deaths occurred: the outcome was a map which revolved around the pump and well. After a struggle to convince authorities that water was responsible, Snow had the handle removed. The epidemic was over and a new theory on germs was born. This one pump represents all modern day efforts to provide clean drinking water to overcrowded cities worldwide. It was simply amazing to actually see the pump, and be grateful for the dedicated efforts of this remarkable British physician. (Read The Ghost Map for an excellent recounting of this story)