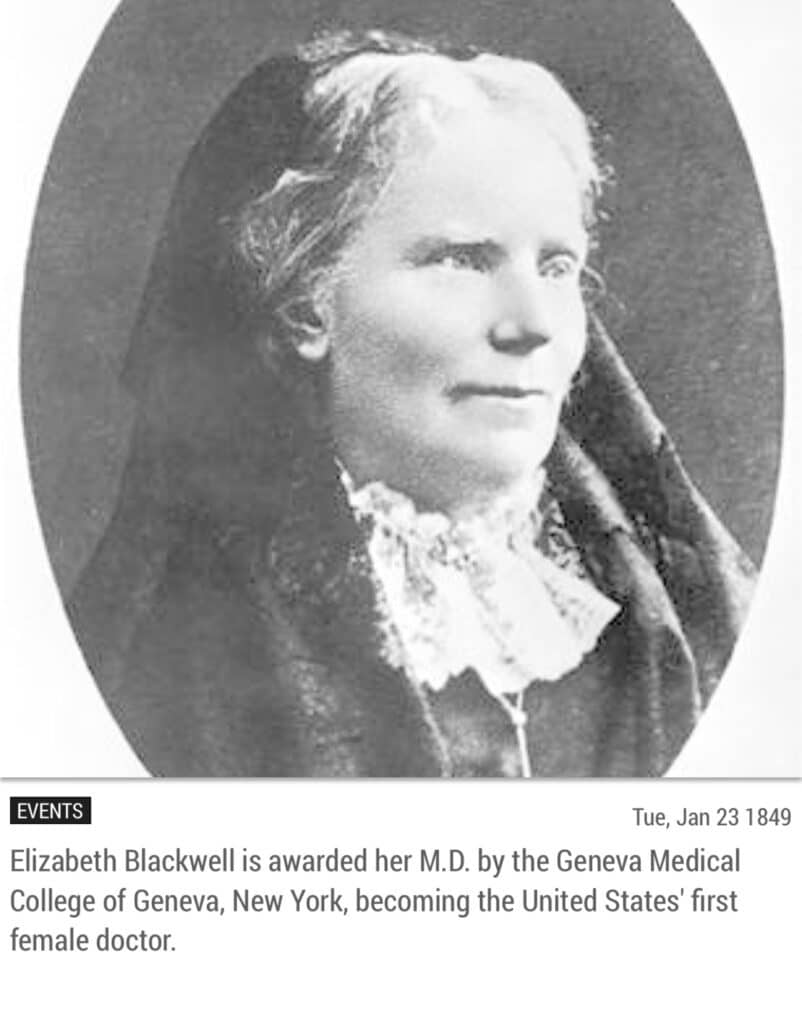

I subscribe to “This Day in History” app, which daily sends along fascinating tidbits of history that happened that day. This past week, on January 23, my phone dinged bright and early: this day in 1849 the first female doctor in America was awarded her medical degree: Elizabeth Blackwell.

Who was this daring and pioneering woman?

This was in a time when medicine was still in its infancy. I read in a book about this era that central Baltimore was an unsanitary backwater without municipal sewers. Bathwater, chamberpot contents and manure flowed across cobblestones. Water was contamination. London would soon be ravaged by a cholera outbreak that later gave birth to public health.

Elizabeth Blackwell was born near Bristol, England on February 3, 1821, the same town that the first family with hemophilia in America hailed from, ironically.

Blackwell came from an unusual family, full of activists. She was the third of nine children of Hannah Lane and Samuel Blackwell, a sugar refiner, Quaker, and anti-slavery activist. Blackwell’s famous relatives included brother Henry, a well-known abolitionist and women’s suffrage supporter who married women’s rights activist Lucy Stone; Emily Blackwell, who followed her sister into medicine; and sister-in-law Antoinette Brown Blackwell, the first ordained female minister in a mainstream Protestant denomination.

A few years after the Blackwell family moved to Cincinnati, Ohio in 1832, the father died, leaving the family broke. Elizabeth, her mother, and two older sisters worked as teachers. Blackwell was inspired to pursue medicine by a dying friend who said her suffering would have been better had she had a female physician. But there were few medical colleges and none that accepted women, though a few women became unlicensed physicians, as did many men.

Blackwell eventually “boarded with the families of two southern physicians who mentored her. In 1847, she returned to Philadelphia, hoping that Quaker friends could assist her entrance into medical school. Rejected everywhere she applied, she was ultimately admitted to Geneva College in rural New York, however, her acceptance letter was intended as a practical joke.

Blackwell faced discrimination and obstacles in college: professors forced her to sit separately at lectures and often excluded her from labs; local townspeople shunned her as a ‘bad’ woman for defying her gender role. Blackwell eventually earned the respect of professors and classmates, graduating first in her class in 1849. She continued her training at London and Paris hospitals, though doctors there relegated her to midwifery or nursing. She began to emphasize preventative care and personal hygiene, recognizing that male doctors often caused epidemics by failing to wash their hands between patients.” *

In 1851, she returned to New York City, and with help from the Quakers, Blackwell opened a clinic to treat impoverished women. In 1857, she and her sister, now also a doctor, opened the New York Infirmary for Women and Children, with colleague Dr. Marie Zakrzewska. They provided positions for women physicians.

In 1868, Blackwell opened a medical college in New York City. A year later, she placed her sister in charge and returned to London, where in 1875, together with Florence Nightengale and Thomas Huxley and others, created the first medical school for women in England. She became a professor of gynecology here. She co-founded the National Health Society in England (which today services people with hemophilia) and published several books, including an autobiography.

She had a fascinating personality, and was a dedicated advocate and activist of many causes. A pioneer in medicine and champion that perhaps many of us in bleeding disorders can appreciate.

*Chicago – Michals, Debra. “Elizabeth Blackwell.” National Women’s History Museum. 2015. www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/elizabeth-blackwell.