Politics and Pandemic

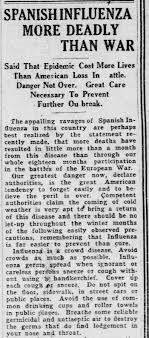

Watching the rally in Tulsa, Oklahoma this past weekend makes for a chilling comparison to 1918. Current concerns about crowding and COVID-19 were fears about the Spanish influenza then. And like the political rally in Tulsa, Philadelphia hosted a huge parade, politically motivated, to attract thousands of people, even though the city was besieged by the pandemic. This influenza was virulent, hostile and swift. Why was a parade scheduled?

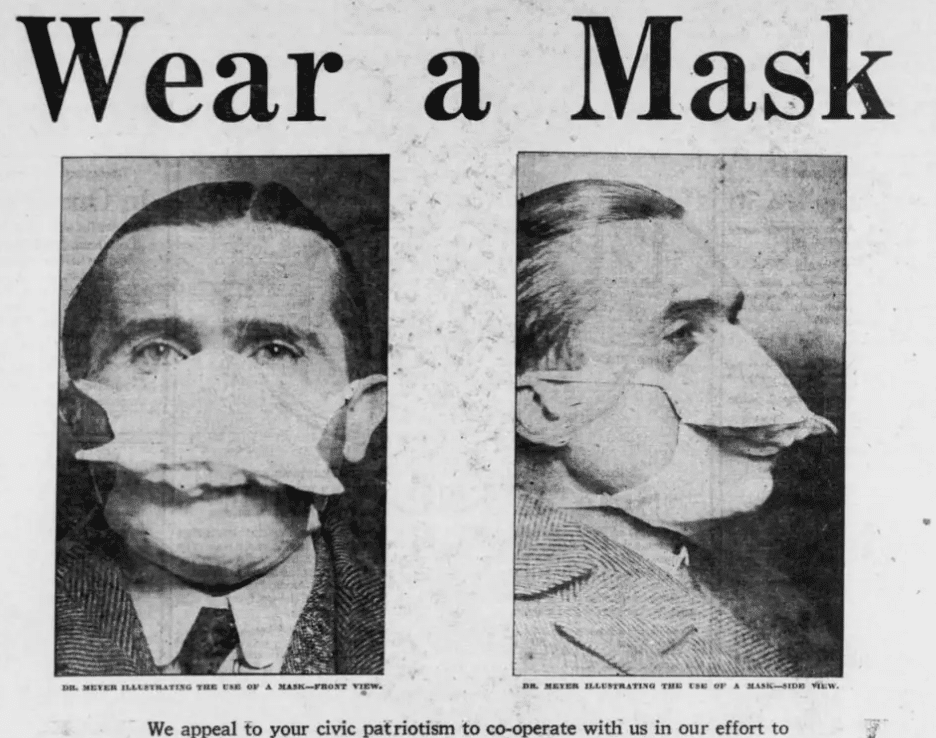

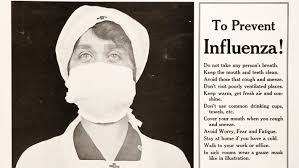

Politics… squelching the voice of science, muzzling the press, and placing political agendas above the safety of citizens. In many ways, we are facing similar challenges, with a public unsure of who to believe. The government? The scientists? The press? In 1918, schools, churches and businesses were shut. People wore masks and practiced social distancing. But it was also wartime, and the drafting of so many young men and crowding them into barracks and hastily made tents during the previous winter helped spread a virus that would kill four times as many Americans as soldiers in the World War II–the Great War.

John M. Barry, in his book The Great Influenza, describes a Philadelphia in 1918 as a steamy, overcrowded city of 1.7 million, with slums. A breeding ground for epidemics. And for political machines: corruption was as widespread as the virus.

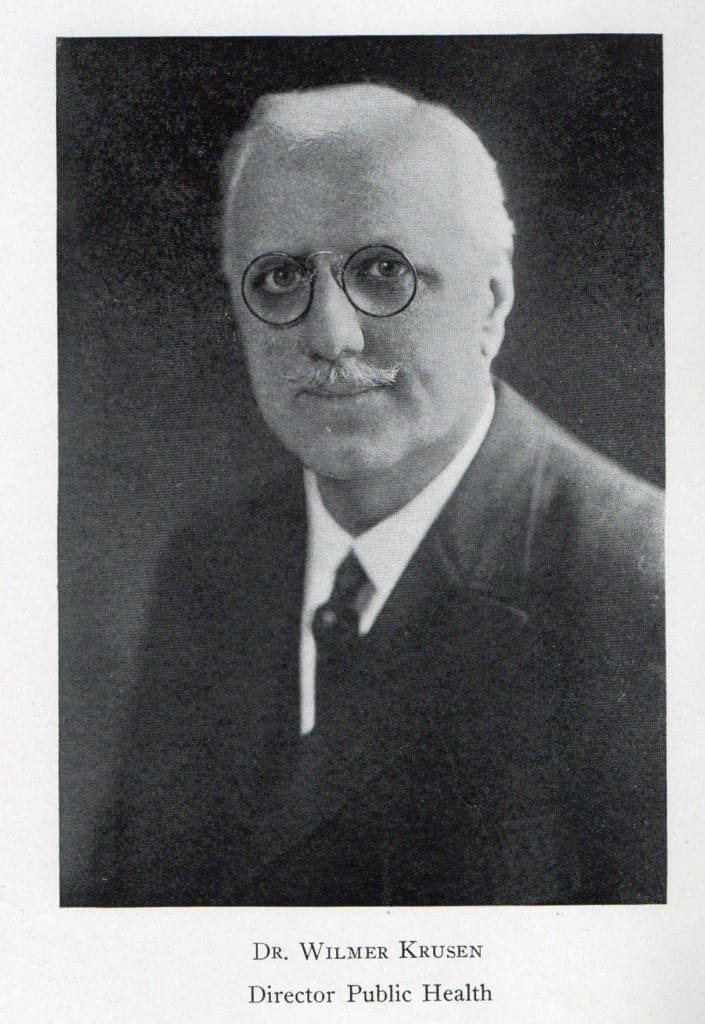

On September 7, 1918, 300 sailors arrived from Boston, where nearly 1,000 had already died. Philadelphia Public Health Director Dr. Wilmer Krusen did not quarantine the sailors. He announced that the ones who died did not die of influenza. Why would he deliberately lie? Philadelphia had a quota to sell so many Liberty Bonds, to raise money for the war effort. The parade would kick this campaign off. Local doctors urged Krusen to cancel the parade. Influenza was spread in crowds.

By September 15, the virus had made 600 sailors sick enough to be hospitalized. On September 17, 5 doctors and 14 nurses in that same civilian hospital took ill. Krusen publicly denied that influenza posed any threat to the city, feared that taking any such steps might cause panic and interfere with the war effort. The parade went on.

Two days after the parade, Krusen announced, “The epidemic is now present in the civilian population.” Krusen, a political appointee, failed in his role as doctor and health commissioner.

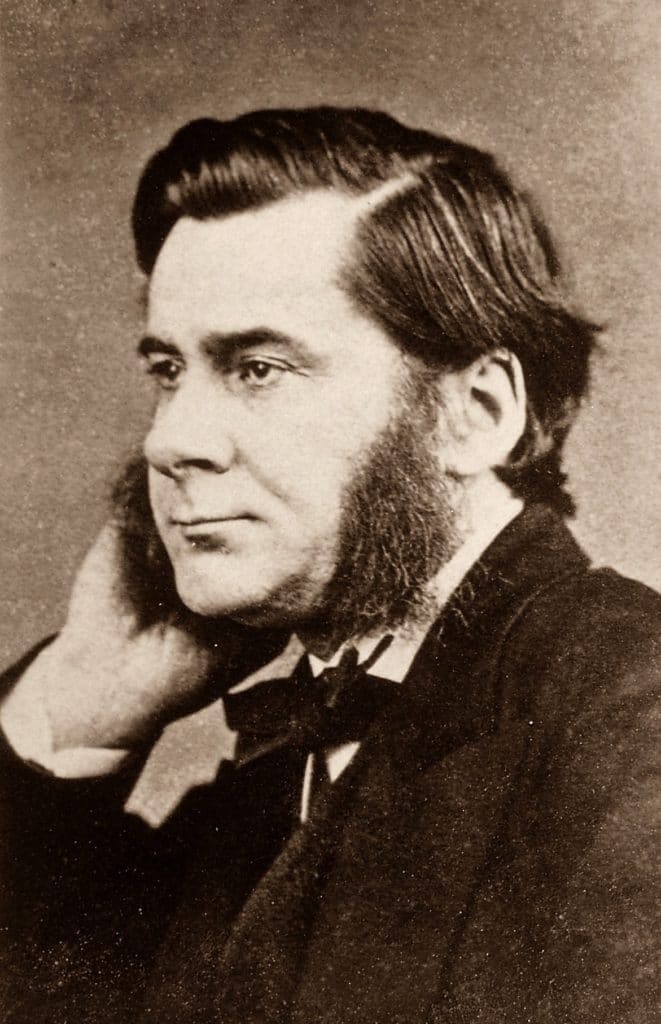

All over the country, as young men gathered to report for war, they fell ill. Dr. William Welch, brilliant head of a new committee to handle the pandemic, wrote to the army to quarantine the new recruits. He knew that one of the best measures to stop contagion is avoiding crowding.

Most army officials ignored the warning. On August 8, a Col. Hagadorn took over Camp Grant. He allowed overcrowding. In six days the hospital went from 610 occupied beds to 4,102. From there, 3,108 troops took a train to Georgia—where 2,000 arrived ill. On October 8, Hagadorn committed suicide.

In Philadelphia, just 72 hours after the parade, every hospital bed in Philadelphia was filled with sick people. Nurses were dying. Corpses lay about everywhere.

But politics still overshadowed the truth. On October 5, doctors reported that 254 people died that day from the epidemic, and the papers quoted public health authorities as saying, “The peak of the influenza epidemic has been reached.” Then 289 Philadelphians died the next day, and the next day 428 people died. Dr. Krusen said, “Don’t get frightened or panic stricken over exaggerated reports.”

47% of deaths in US now were from the Spanish flu.

The civilian health care system was in trouble, as the government took as many doctors and nurses as possible for the war effort in Europe. Lab animals were unavailable for testing vaccines. Masks, protective gear was scarce. Everything went to equipping the war machine.

And politics went on. Back on January 1,1918 Tammany Hall regained control of New York City. Patronage determined jobs but most jobs in the Department of Health were not patronage positions. No problem. Tammany began to smear the best municipal health department in the world. Division chiefs were fired, and highly respected physicians on the advisory board were removed. The new health commissioner, Royal Copeland, was dean of a homeopathic medical school, and not even a doctor of medicine! Perhaps he was appointed because the bosses knew he would not cause trouble. They were right.

“The best municipal public health department in the world was now run by a man with no belief in modern scientific medicine and whose ambitions were not in public health but in politics,” writes Barry.

On September 15, 1918, New York City’s first influenza death occurred. Commissioner Copeland assured the public “that the disease is not getting away from the control of the health department but is decreasing.” Eventually, the death toll reached 33,000 for New York City alone.

And what of the president?

“Wilson took no public note of the disease. From neither the White House nor any other senior administration post would there come any leadership, any attempt to set priorities, any attempt to coordinate activities, any attempt to deliver resources,” writes Barry. “No national official ever publicly acknowledged the danger of influenza.”

In Philadelphia, the government not only did nothing to help, it lied to the public that the virus was not anything to worry about, when death was everywhere. During the week of October 16, 4,597 Philadelphians died from influenza or pneumonia. The wealthiest families who controlled the charities got to work, and brought aid, when the government didn’t. From corpse transport, to soup kitchens, they pitched in personally and with volunteers.

And the press was distorting the news, but they were muzzled as well by the national government, for the “war” effort, but it went far beyond that. “People could not trust what they read. ‘Don’t Get Scared!’ was the advice printed in virtually every newspaper in the country, in large, blocked-off parts of pages,” Barry notes. Politics interfered with freedom of the press perhaps greater than in any time in history.

Barry goes into great detail about the virus, and the many attempts to create a vaccine. Ultimately, the virus began to die out. There was a second wave, and even a third. Numbers spiked well into 1920.

He postulates on an interesting outcome, though there were many as a result of the feverish pace to identify the culprit, the source and a cure.

President Woodrow Wilson became very ill just before the Paris peace talks in 1920, which would lead to the Treaty of Versailles, to dictate the terms of surrender for Germany. Wilson and his American team had a set of standards and policies that were nonnegotiable. Did Wilson contract the virus? Was he that ill?

“Abruptly, still on sickbed, only a few days after he had threatened to leave the conference unless Clemenceau yielded to his demands, without warning to or discussion with any other Americans, Wilson suddenly abandoned principles he had previously insisted upon. He yielded to Clemenceau everything of significance,” Barry writes.

Four months later Wilson suffered a debilitating stroke. Was it from hardening of the arteries, or from the Spanish flu, which was known to affect people’s minds? What is known is that the Paris peace treaty helped foster the economic hardship, rising nationalism, and political instability that helped the rise of Adolf Hitler.

Barry ends his excellent 2004 book with prophetic statements. Think about these as we endure our own current pandemic.

• “The CDC estimates that if a new pandemic virus strikes, then the U.S. death toll will most likely fall between 89,000 and 300,000.”

• “An outbreak would quickly fill beds in intensive care units, so resources need to be available”

• “Public health officials will need the authority to enforce decisions, including ruthless ones.”

• “Officials must have in place the legal power to take extreme quarantine measures.”

• “But there is another lesson from 1918 that is clear. It is also less tangible.”

It involves the use of fear as a tactic: through the media and the way our elected officials deal with the public.