John M. Barry, in his excellent book The Great Influenza, notes that it cannot be proven that the 1918 “Spanish” influenza originated in Kansas, but there is circumstantial evidence, and it sure didn’t originate in Spain. Why then was this influenza, which would kill an estimated 25-50 million people globally christened this? Because the press was muzzled in the US, mostly due to the war, but also because President Wilson did not want fear of the flu to keep young men from enlisting and serving their country. More would die at home, of the flu, than on the battlefield: 675,000 versus 115,000. A staggering difference. Only Spain, which was neutral during the war, kept its press free and open, and it warned of this deadly disease. So, it was dubbed the “Spanish flu.”

From one known case the influenza virus traveled to Camp Funston in Kansas in early 1918. Within three weeks 1,100 troops at Funston were hospitalized. From there it traveled fast and far. US troops were shipped to Boston. It spread quickly there. Troops were then shipped off to Europe: nearly 40% of the two million American troops who arrived in France disembarked at Brest, France. By early April, the flu had arrived there; later that month, it hit Paris and Italy. The British army recorded their first cases mid-April, and then… a full scale, raging pandemic. Even German troops in the field reported the devastating effects. General Ludendorff actually blamed the loss of one military initiative on the flu!

On June 30, 1918, the British freighter City of Exeter docked in Philadelphia, carrying influenza. But Rupert Blue, the civilian surgeon general and head of the U.S. Public Health Service, issued no instructions to the maritime service to hold influenza-ridden ships! Dozens of ill crew members were taken immediately to Pennsylvania Hospital, seemingly with pneumonia. When they died, two physicians publicly stated to newspapers that they had not died of influenza. They were lying. Why would health officials lie?

Politics. “Those in control of the war’s propaganda machine wanted nothing printed that could hurt morale. The disease did not spread,” Barry writes. So the disease continued to decimate soldiers as no war could. Soldiers continued to be shipped out, and with them, the real enemy–influenza.

All that summer of 1918 England, Scotland, and Wales reported surges in cases, and deaths. Denmark, Norway, Holland and Sweden. After a military transport arrived in Bombay, India, the number of cases soared. The virus hitched a ride on the railroads of India, and soon it reached Shanghai. New Zealand and Australia in September; and Barry reports that 30% of the population of Sydney became ill. But the disease was rather mild still; in the French army, fewer than one hundred deaths resulted from 40,000 hospital admissions. The journal The Lancet (so named after the blood-letting device) published a report that perhaps this was not even influenza! The disease was fatal within 24-48 hours, which didn’t match what was known about influenza then. And it was noted that in Louisville, Kentucky, 40% of those who died were aged 25-35; usually the flu hits the most vulnerable: the very young, the very old and the sick. What was this disease?

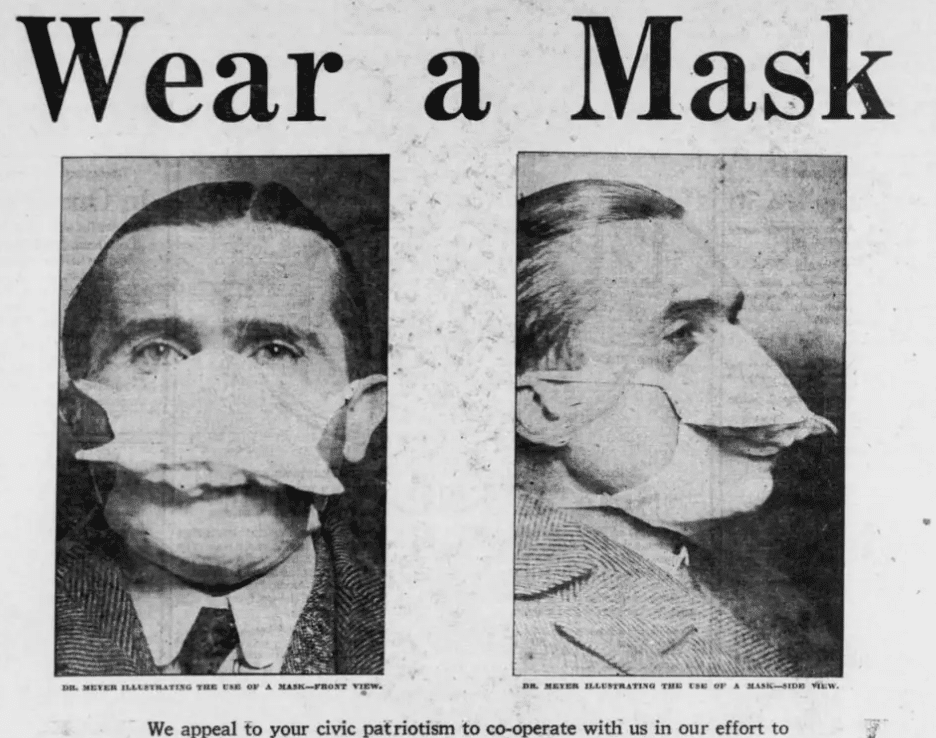

Then, oddly, it was gone. On August 10, the British high command announced the end of the epidemic. Life started returning to normal. Churches opened, schools started. People stopped wearing face coverings, and avoiding one another.

But the virus was not gone. It had only retreated, quietly mutating, like a stealthy enemy revising its attack strategy. On the same day the British army declared the pandemic over, French sailors stationed at Brest were hospitalized with influenza and pneumonia in such vast numbers that they had to close the naval hospital. The influenza virus, like many other pandemics, was mutating. And it was mutating into a killer of unimaginable proportions.

Next week: The world at war, the treatments, the outcome.