Start of Our Trek! April 2-6, 2017

|

| Jess and Chris Bombardier |

|

| Laurie Kelley in Lukla |

We walked about town while waiting for Rob’s luggage to arrive. I bought a used fleece buff, which I needed later. We visited a monastery there, which was amazingly beautiful. We also strode up to a stupa, to see the fluttering prayer flags with the Himalaya as a backdrop. The name Himalaya means home (alya) of snow (hima).

We walked about town while waiting for Rob’s luggage to arrive. I bought a used fleece buff, which I needed later. We visited a monastery there, which was amazingly beautiful. We also strode up to a stupa, to see the fluttering prayer flags with the Himalaya as a backdrop. The name Himalaya means home (alya) of snow (hima). |

| Everest National Park |

|

| Chris and Ryan watch the yak caravan |

|

| Mani Stones: “Om Mani Padme Hum” |

|

| Laurie Kelley and Chris Bombardier on a suspension bridge |

|

| Dodh Kosi River |

After an hour we made it to Namche Bazar, a famous stop over for trekkers. I could only think about crawling into bed. Chris made me feel better by saying that the group only had arrived 10 minutes ahead of me, but it felt like an hour.

After an hour we made it to Namche Bazar, a famous stop over for trekkers. I could only think about crawling into bed. Chris made me feel better by saying that the group only had arrived 10 minutes ahead of me, but it felt like an hour.Thursday April 6, 2017

There were long sections of uphill climbs, through pine trees. We slogged away, step by step. I’d pause to breathe and let porters hike by. It’s amazing how much the porters carry. One porter carried enormous slabs of plywood, four sheets at about 8′ by 4′, and he all of 5′ tall. Another old porter carried a washing machine box on his back, and a rucksack, and another box. It was three times his size.

There were long sections of uphill climbs, through pine trees. We slogged away, step by step. I’d pause to breathe and let porters hike by. It’s amazing how much the porters carry. One porter carried enormous slabs of plywood, four sheets at about 8′ by 4′, and he all of 5′ tall. Another old porter carried a washing machine box on his back, and a rucksack, and another box. It was three times his size.  |

| Prayer wheels |

Lhakpa was no where to be seen. So I waited in the shade, and gazed at the amazing, peaceful monastery. I was amused to see the shaved-head monks walking about in their crimson robes, with Nike sneakers on. I went inside the monastery, removing my dirty hiking boots. Outside, the most peaceful of scenes: grass, stupas, three beautiful horses grazing until three rowdy dogs chased them. A helicopter landed, sending a yak scurrying, depositing a trekker. Fluttering prayer flags provided bursts of color everywhere. Inside, a sole monk chanted prayers, fingering his beads, while trekkers like me sat quietly around the perimeter on mats, waiting. The room was brightly painted with scenes of Buddha.

Lhakpa was no where to be seen. So I waited in the shade, and gazed at the amazing, peaceful monastery. I was amused to see the shaved-head monks walking about in their crimson robes, with Nike sneakers on. I went inside the monastery, removing my dirty hiking boots. Outside, the most peaceful of scenes: grass, stupas, three beautiful horses grazing until three rowdy dogs chased them. A helicopter landed, sending a yak scurrying, depositing a trekker. Fluttering prayer flags provided bursts of color everywhere. Inside, a sole monk chanted prayers, fingering his beads, while trekkers like me sat quietly around the perimeter on mats, waiting. The room was brightly painted with scenes of Buddha.Searching for a Stone and Unexpected Luck

Thursday

March 30, 2017

This was easily our best day in Nepal, packed

This was easily our best day in Nepal, packedwith adventure, home visits and a deep appreciation of Nepal, its people and

the Nepal Hemophilia Society. Manil showed up with two vans: the production

team of Believe Ltd—Patrick James Lynch (director), David Beede (sound), Josh

Bragg (video) and Rob Bradford (photography)—pile onto one van, but first, they

tape a GoPro to the front of the van to capture the frantic, physics-defying

Kathmandu traffic. Chris, Jess, Manil and I get into the other van and off we

go. We leave the capital area and venture into the countryside, where the urban

concrete jungle turns to trees and farms, cattle and hay. We’re on our way to

see Bibesh, a 19-year-old with hemophilia and a beneficiary of Save One Life. It

rained last night and while creeping uphill on a dirt road, our van gets stuck

in a muddy washout. The production vans zips by while the guys laugh at us and

disappear around a hill. We all have to get out. We grab our bags and the bags

with gifts and start to walk. Around the hill? The production van, also stuck.

Manil tells us it’s about a half hour walk to

Bibesh’s home. The guys are carrying in total about 130 pounds of equipment:

cameras, batteries, cases, microphones. Josh props his enormous video camera on

his shoulder practically the entire walk. As we walk, the Believe crew

interview Chris and Mani. Jess and I hang together as we walk. The road is

thick with mud, and luckily we are all wearing our hiking boots. But it’s

pleasant: the air is moist and refreshing, and the view is stunning. Tilled,

green hills, brick cottages, cows. The valley stretches before us, decorated

with trees and crops. Somewhere far away we can hear music, and strangely, a

cuckoo!

It’s here that Mani tells us he will need to wait while we go on. He is

limping, and his arm is in a sling. I’m sure he must feel pain but he doesn’t

complain. After we slip down the hill, we stroll out

into a huge green field, following a trail. We’re in the middle of nowhere it

seems as the village we just went through recedes. Down the trail, we have to

cross a stream, and the only means is to balance on a plank. Yes, a plank!

Patrick goes first, then me, then Jess, who clowns around. Then up a hill, very

steep, and it leaves us huffing and sweating. We come to a cottage, but it’s

not Bibesh’s so on we go. It’s getting to be surreal, that this young man has

to overcome roots, vines, mud, hills and a very long walk, just to get to a

bus, that would then take him another hour to get to the hospital to treat a

bleed. And none of them complain, or curse their fate. Ever. They hope—hope

that we can help them, and they ask. But they don’t demand, argue or get

vengeful.

At last we reach Bibesh’s home, high on the

At last we reach Bibesh’s home, high on the

hill. It’s made of brick, but has obvious cracks in it from the earthquake. The

porch is propped up with poles. All around is dusty earth. In fact, they don’t

live in the house but live in a shed, and are building another home up another

hill. The guys get their cameras and sound gear ready. Bibesh is 19, and

actually just had a birthday yesterday. His mother Uma is present, and his

81-year-old grandmother, Bed Kumari, who is as frail as a little sparrow, with

deep set eyes, skin the texture of leather, with many deep creases. Her face is

remarkable, and I photograph her. The lines are like chapters in a book, and

she has a long, amazing story to tell, if only she could. We have a shocking

moment when the great-grandmother appears! She’s a bit wild, with grizzly hair,

missing teeth, rail-thin body, and darting eyes. She speaks in Nepalese very

loudly, and the family motions that she’s hard of hearing. We all get a kick

out of her.

a shop, and earns about $180 a month. The sponsorship he gets through Save One

Life is $24, so it definitely helps. They own their home, which is good, but it

is in bad shape now.

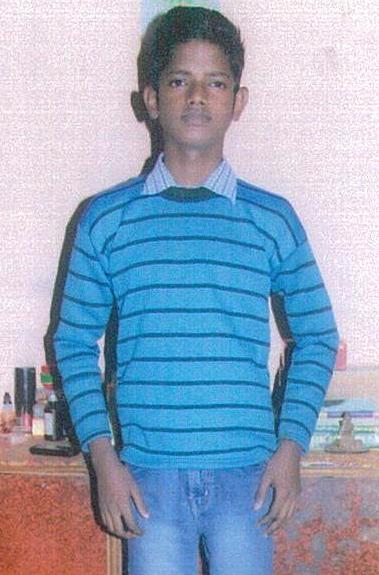

Bibesh himself is a handsome young man, well

Bibesh himself is a handsome young man, welldressed and soft-spoken. He speaks English pretty well. He gives us a tour of

the property. We go inside the condemned house, which is more narrow inside

than it looks. We have to duck; the stairs are creaky and threaten to give out.

It’s dusty and damp, with a concrete floor, no screens in the windows. Chris

goes upstairs where the bedrooms are, and Bibesh shows us how the main beams in

the house split under the stress of the quake. Cracks appeared in many of the

bricks too. Outside, we take a short trip up the hill some more and see the new

house under construction. While they use bricks, the mortar seems inadequate to

keep the bricks together. The family is proud to show us a beautiful brick

temple they are also building.

and as I take one with my hand I burn it—ouch, I shout! Hot tea!

watches me, and we hug and she nestles into my arms. She is so thin—you can

feel all her spine and shoulder bones. Such a lovely old woman. I wonder what

she makes of all this: cameras, strangers, interviews.

When we leave, Josh gets the drone ready to

take aerial photography. It sounds like a huge bee buzzing overhead. Going down

the hill proves to be just as challenging as going up. We slip and slide our

way down the hill, back to the stream. Chris and Bibesh chat as they descend,

with Josh filming.

It’s a one hour ride to see Om Krishna, a

17-year-old. We stare out the window and see miles and miles of concrete

bricks. Made right from the mud, the bricks are formed, stacked and then

carried on the backs of men, to make long walls of stacked bricks to be sold.

Beyond the brick-making farms, we approach Om

Beyond the brick-making farms, we approach OmKrishna’s town. The neighborhood is pretty, with some big homes. Om Krishna’s

home is also big, but uninhabitable—earthquake. The family moved from it into a

shed, something we would use to store gardening tools. It really seems wrong

that they should be living there, especially so long after the quake. Not only

does the whole family turn out but the whole neighborhood! Children spring from

nowhere and smile shyly and hide behind adults. Patrick and team waste no time but get right

to work setting up the equipment and proper places to film.

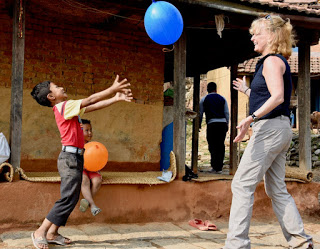

adorable little cousins. Jess and I brought school supplies from Colorado, and

puzzles and punching balls donated from the New England Hemophilia Association.

These were all big hits! Om Krishna is a handsome young man, who speaks English

almost perfectly. He’s a good student. He confides in me after the interview

that he worries about continuing school, as his father is a driver and doesn’t

earn much.

One thing Om Krishna is rich in is family.

It’s obvious he is surrounded by love: a beautiful, elegant mother, who,

despite their struggling status, walks with dignity and grace, her sari gently

flowing. She beams at her son. So does the grandmother, with a face etched with

years but with a warm smile for this special young man.

Sadly, Om Krishna’s little brother died of an

untreated gastrointestinal bleed. He still has a hard time talking about it.

This is difficult in some cultures. When you have one child with a disability,

it’s considered unfortunate. Two? That’s a curse. The family could risk being

ostracized from the neighbors for something like this.

into the vans and head to the last house of the day: the Rajbchak

family. After another hour long drive (poor Jess kept feeling car sick), we

arrived, and pulled up alongside a roadside shop I know well. Behind the front

counter was Jagatman (age 26), a Save One Life success story. Jagatman owns

his own mobile repair shop, after receiving training funded by Save One Life,

and then a microenterprise grant.

When I stepped out of the van and up to his shop, he smiled broadly

and we both said namaste. He looks great! Confident, strong, which is

remarkable as he has an artificial leg, also a gift from Project SHARE. The

shop is perched at a cross roads and has an open front that displays watches,

toys, picture frames and candy. Soon his brother Jagatlal, who goes by the

nickname “Monsoon,” appeared. We hugged each other (after all, we are friends on Facebook now). Monsoon speaks English fluently and translated for us.

Again, Patrick and the Believe team got right to work and right there, in the

middle of the street, after pulling up chairs, began interviewing Jagatman. A

crowd gathered. Patrick asks excellent questions and gently guided Jagatman and

Monsoon through what is it like to have hemophilia in a developing country.

of noises emanating from the street: motorbikes, cars and a really loud three

wheeled motorcycle that had metal pipes on it that obviously rattled and banged

each other while it took the corner near the shop. Patrick almost packed it in

then!

Dave filming. Somewhere electronic music from a dance club was playing, so

loud! It’s a wonder they could even film.

pile of bricks. The family lives across the street in a shed as well, much

bigger than the others I saw. Outside the entrance of the shed, the boys’

mother waits, ready to offer us hot tea. So nice! We filmed it all and finally

had to call it a night. It was pitch black now, and we still had an hour ride

ahead to get back to the Shanker Hotel.

Going back to the street corner

store, we said goodbye to Jagatman. The boys’ father bought a fresh yogurt

drink from the store next door. It was refreshingly delicious. The Nepalese hospitality

and civility never fail to amaze me. Here’s a family with two boys with

hemophilia, one who lost his leg, and a family that lost it’s entire house, and

they are buying us yogurt drinks!

thoroughly exhausted when we drive back. Jess is the first to fall asleep in

the van, then Chris. It’s emotionally draining to visit, view and hear the

stories of loss, and wonder how these families find the faith, will and

reserves to continue.

one piece of good news that day: the 4 million IU donation of factor just got an

upgrade. 5 million IU, the largest single donation in Nepal’s history. Thank you

Octapharma. Just made my night.

Aim to Fly and Touch the Moon

Kathmandu, Nepal after 18 months, and still there are so many signs of the massive earthquake that rattled the country on April 25, 2015.

The

air quality remains poor: my throat feels raw and my eyes water. Our team wears filter

masks strapped to our faces, to protect our lungs. The city at night pulsates like a

living being: through the streets motorbikes, cars, rickshaws, trucks flow,

belching out waste, laced overhead by a gnarly grey network of telephone wires

and cables at each street corner.

I’m here with the crew from Believe Ltd, who will be filming hemophilia B patient Chris Bombardier as he meets with the Save One Life program partner, the Nepal Hemophilia Society (NHS), and patients, and prepares for his Everest attempt. Chris’s wife Jessica accompanied him and will trek with us to base camp. She and I will stay two nights, then come back to Kathmandu while Chris stays another month, acclimating for the big climb. Should Chris summit, he will be the first person in history with hemophilia to conquer Everest. With

I’m here with the crew from Believe Ltd, who will be filming hemophilia B patient Chris Bombardier as he meets with the Save One Life program partner, the Nepal Hemophilia Society (NHS), and patients, and prepares for his Everest attempt. Chris’s wife Jessica accompanied him and will trek with us to base camp. She and I will stay two nights, then come back to Kathmandu while Chris stays another month, acclimating for the big climb. Should Chris summit, he will be the first person in history with hemophilia to conquer Everest. Withall the camera equipment, and Rob Bradford (photography), Jess, Chris and I in another, so Rob can

film. I enjoy their wide-eyed first look at Nepal with all its helter-skelter traffic

and humanity.

First stop today, Tuesday, March 28, is the Bir Hospital, where I’ve been three times

First stop today, Tuesday, March 28, is the Bir Hospital, where I’ve been three timespreviously. I first came to Nepal in 1999 for an assessment visit, then returned in 2000, when my company funded a medical conference. I was so impressed with the NHS then. And more so now. The NHS became our second program partner for Save One Life solely based on their ability to get the job done right, and fast. They are a crackerjack team and work hard to help their patients.

traveling with a film crew this time. I’m used to moving fast and ducking in and out. But

with about 200 pounds of camera and sound equipment, we have to move carefully

and cautiously. The hospital is still in disarray following the earthquake. It’s dark and uninviting. But the hemophilia treatment ward is brightly lit,

clean and orderly. No patients are there at first, and while the crew films,

we chat with the two lovely nurses.

A high number registered! About 200 make regular visits to the HTC, also a

high number. The center is now open 24 hours a day, which is excellent. They have a small

fridge, under lock and key, for factor. Inside is the Biogen/WFH donation of

Alprolix and Eloctate. This donation is absolutely revolutionizing care,

because it provides consistent product availability, which allows for planning, which leads to a

changed mindset. (I will write more about this in the August issue of PEN).

The nurses slipped silk scarves about our necks and greeted us with

The nurses slipped silk scarves about our necks and greeted us with“Namste!” as we each entered. The ward was upgraded! Freshly painted, with new

offices for factor storage and for the nurses’ office; it looks excellent. A freezer held

fresh-frozen plasma, something you never see in the US; this is for patients

with rarer factor deficiencies, or for when there is no factor.

Then a patient walked in: 18-year-old Bibek, a handsome, tall young man,

slender, with an apparent elbow bleed. Despite what must be searing pain, he

smiled broadly, was calm and accepting, gracious. It’s how the Nepalese are:

deeply ingrained in each seems to be a gentle approach to life, respect for

all, and profound civility. They have much to teach the world about how to get

along with others.

We chatted with him and learned he had to travel 3 hours to reach the

We chatted with him and learned he had to travel 3 hours to reach theHTC for one injection of 1,000 IU, not even enough for his lanky frame. And the

elbow bleed started the day before. He didn’t put ice on it because there is

none where he lives. Still he smiles; his face is placid and open, inviting.

His English is excellent.

hallway, then enter again, replay every conversation and act. We joke it’s

Bollywood and we should sing and dance our way in. Think the ending of Slumdog Millionaire! So we comply and redo the entire entry, greeting,

conversation. I ask them to include the photo of the mom who died in the

earthquake, while she was assisting in blood donations. She’s a true hero.

Ashrit. I regret that I didn’t recognize him at first. We chatted, and he

lifted his leather jacket sleeve to reveal a clawed hand: Volkman’s

contracture. Repeated bleeds for four years have left his left hand useless,

and in a permanent grasp. The saddest part is that he loves to play guitar. I

ask who his favorite guitar player is and he rattles off a long list: Jimmy

Page, Angus Young, Jimi Hendrix… “Slash?” I ask. Oh yes! He’s amazing! So we

share stories of guitar players and music, and he knows how to play Sweet Child

O’ Mine (one of my favorites). He even learned to play with one hand and had Jess and me listen to a

recording on his phone. It’s beautiful. He has talent. He also shows artwork, a

pencil sketch of a child, which is beautiful and haunting.

motorcycle? And I picked at his leather jacket. He started laughing, and I said

I know you Nepalese boys and your motorbikes! He said he used to but not any

longer. Such a sweetheart. He needs surgery. The

main problem? He has an inhibitor. Life has dealt this young man a double blow

but still he smiles and has dreams. I want to help him get surgery.

After

Afterthe Bir Hospital we drove to the Nepal Hemophilia Society office, in the

residential district. Some wiry teens were playing cricket in the street; birds

chirped, the sky was overcast and the air cool. Inside was crowded. They had

built out the office, including a new cold room, to store the donations from

Biogen; this means they could easily handle our proposed 4 million IU donation.

Manil Shrestha (also a patient) and his team are doing a great job. We asked questions, Believe Ltd. filmed… all good material for the documentary.

Mani suggests we go to “KFC,” which

we all think means Kentucky Fried Chicken. We scuffed across the dusty street,

to the main street, with cars, motorbikes and trucks bulleting past us. It’s

very dangerous to cross. Up the high curb (we have to help one another) and

into KFC: Kwik Food Café. I’ve eaten here before. The bathroom sported a squat

toilet, which is actually hard for patients with hemophilia to use–just think about it. Nepalese food is excellent and we down dumplings (called momo),

French fries, noodles, vegetables and Cokes. The talk is happy and light, and

everyone has a good time.

On the way back I witnessed a tender moment seeing Patrick

On the way back I witnessed a tender moment seeing Patrickchat with Beda Raj, a board member and also patient, and hold hands, which is the custom here among close male friends. Patrick is a rising star in our community: driven, ambitious, articulate, with a kind heart and compassionate soul. He

lost his 18-year-old brother Adam and it has impacted him greatly. Afterward,

we head for the Shanker hotel, and have dinner together at 7 pm. Everyone has Everest

beer and I have wine, and we share stories from the day.

March 29, 2017

It was rainy, which was disappointing, but then the air was remarkably cleaner

and easier to inhale. We start our day in the dining room together, and I enjoy

a breakfast of eggs, croissants, muselix (delicious), fresh watermelon and

mango, and steamy masala tea. Everyone is obsessed with their photos and we compare them.

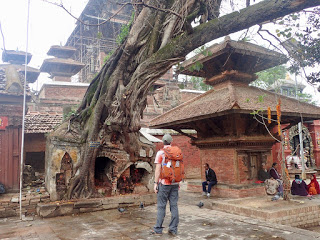

Then off to Swayambhu, the “Monkey Temple,” close

by. We draw a crowd because of all the camera equipment. The focus is entirely on Chris; making a pilgrimage to this most famous of temples, in preparation for his climb. I feel very much at peace in Swayambhu. The colorful prayer flags

dance in the wind around the stupas with the painted eyes of Buddha watching. Stray

dogs, their tails eternally curly, strut about in the rain or sleep at the base

of the stupas or even inside the arch of the little temples to escape the rain. Bold macaque monkeys leap and swing overhead, fighting with one another, scanning

for food. They are a rough lot; some are missing patches of fur, and one is

actually missing a nose. One baby has a mangled leg he drags about. Birds chirp

and somewhere a cuckoo chimes.

level, where the gift shops are. The rain is pelting but I have an umbrella and

water-proof camera. I’ve been here twice before and so just enjoy it all. Other

trekkers are here, maybe German. I’m intrigued as always by the Hindu masks on

display. Jess and I meet up and I film her spinning the prayer wheels.

wouldn’t be? He didn’t set out to make a documentary, only to climb the Seven Summits

for a cause–Save One Life. Shy by nature, he comes across as

authentic, humble, and people will be drawn to that. So soft-spoken but a core of steel!

at the temple, and candles at another temple. A monkey bolts up, grabs an

offering of food meant for the gods, and scoots away. They are fast and mischievous. There’s still

earthquake damage, manifested in cracks in the buildings and piles of bricks which is so sad at this ancient of sites. The rain came and went, as we walked about. It took a while to get the tickets, and we stood on a street corner watching all the people walking by. Women with lined faces and colorful but damp saris tried hard to sell us trinkets: bracelets, necklaces, purses. “Good price I give you,” “Madame for you?”

Off to Nepal.. and Everest

|

| Laurie Kelley with Youth Group, Nepal Hemophilia Society September 2015 |

|

| Chris infusing on a summit! |

Because he has hemophilia–a “disability.” Huh. Chris has a few things to show the guys in Antarctica.

|

| Waiting to see this on Everest! |

From the bottom of our hearts and hiking boots we wish to thank Octapharma for completely funding Chris’s climb, and Believe Ltd.’s documentary. While there is no amount of money that can compensate Chris for his time and personal risks, none of this adventure and effort would be possible without Octapharma’s generous support and more importantly, its belief in Chris and Save One Life. Chairman Wolfgang Marguerre has been one of Save One Life’s biggest supporter and sponsor of children with hemophilia in developing countries. He truly believes in our mission. Thank you Mr. Marguerre and all your colleagues, including Flemming Neilsen and Carl Trenz, for your help and support!

If you would like to sponsor a chid in need, visit www.SaveOneLife.net to learn more. Together we are improving lives with hemophilia…one at a time.

Wednesday’s Child*

Month, Save One Life, the nonprofit I founded, is sharing stories every Wednesday in March to illustrate the

challenges and triumphs of children and adults with hemophilia in the

countries we serve.

you to become a champion of our cause–reaching out to family and friends to

encourage them to sponsor a child or donate to a program. We have about 30 children in need of sponsorship–please visit our website and see these beautiful children who deserve someday to celebrate too.

Rathish became a Save One Life beneficiary when

Rathish became a Save One Life beneficiary whenhe was 17. At that point he had suffered so many untreated bleeds, he could no

longer walk. His mother would carry him in her arms, even as a teenager, or he

would use a wheelchair. Living in the country, he was confined at home, unable

to go to school. For activities, he played on the computer, drew and watched

TV.

$50 per month. His older brother, Sudhish, who doesn’t have hemophilia, works

as a welder to supplement the family’s income.

Usha Parthasarathy, met Rathish, she was particularly touched by his condition.

She organized a fundraiser to pay for surgery on Rathish’s knees at a

hospital 50 miles away from home. His mother used his sponsorship money to help

defray other surgery-related expenses.

for Rathish to walk again, with the help of braces and crutches. Now at age 21,

he continues to build his strength with exercises and walking every day. He is

home schooling at the 10th grade level, and honing his computer skills.

Inderjeet from India

This is a sad story, as Inderjeet, 15, passed

This is a sad story, as Inderjeet, 15, passedaway on February 28 from a CNS bleed. The only son of his parents, Inderjeet complained

of a headache on Sunday evening. After dinner he became sick, so his parents

made the two and a half hour trip to the hospital. The medical team determined

he had a CNS bleed and infused factor.

another hospital with better facilities–a drive through busy city streets in

Delhi–but when they arrived, the hospital did not have a bed for him. He had

to go back to the first hospital. This proved to be too much. Emergency surgery

never happened and limited factor infusions were insufficient to save this boy,

who loved art and wanted to be an engineer.

In his most recent update to Save One Life, he was grateful to his sponsor and

expressed his love for her.

—A. E. Bray’s Traditions of Devonshire (Volume II,

pp. 287–288), 1838