| More like 2.5 hours! |

“I feel as though the cardboard box of my own

reality has been flattened and blown open. Now I can see the edge of the

world.” ― Tom Hiddleston, on an African UNICEF UK mission.

two and a half hour drive north from Kampala. This time the

van came at 9:30, giving me a chance to sleep in. The sky was

cast in pewter, heavy and foreboding. Agnes and I again stopped at a roadside store to stock up

on groceries for the family. In the back of the van we still had gift bags brought from home for

the kids. We loaded up on rice, sugar, coffee, tea, lollipops… then I discovered a toy aisle!

Balls, dolls, puzzles, building blocks, crayons and paper: all very inexpensive, and I knew they would be a big hit.

|

| Agnes Kiskye, executive secretary of HFU |

|

| Herding Ankole Watusi cattle |

As we drove away, I absorbed the many sights of Uganda: red, rugged

roads; little boys herding enormous Ankole Watusi cattle—startlingly beautiful animals with

saber-like horns that generally steal all the attention at farm shows; a man

riding a bicycle carrying huge 2x4s sideways; a woman balancing baskets of

vegetables. There are not many cars as we leave the city; only bicycles, as most people get

about on foot.

|

| The rains in Africa |

The sky caved in, loud bullets of raindrops assaulting the roof in an ambush. During

the rainy season, the heavens gush water as if from a hose. We

could barely see the road ahead of us–but we could feel it. The pavement once again turned to dirt as we drove

deeper into the countryside. Mud splattered and huge puddles formed in the ruts

in the road. We jostled and bumped, watching the poor pedestrians get soaked.

As we drew close to the home of our next family, the countryside became

desperately rural. Green, lush and rich with minerals,

everything grows in Uganda: bananas, tea, and coffee. Most families engage in

subsistence farming, meaning they farm for themselves and sell whatever they

have left over.

|

| Sseempa home in the rain |

Ssempa family, blocks made from the local soil. By now their dirt front yard was

a pond. Whereas yesterday I told the driver to stay away from the house so I

could snap photos without the van in front, this time I asked him to pull up as close as possible. I was

wearing tan Etienne Aigner open-toed sandals, as old as the hills, but still!

Grabbing all our bags, umbrella, briefcase, we plunged our feet into the warm, rusty-colored

water and took two steps into the home, which we quickly saw had no floor. Just

dirt. It only had two rooms in the front, maybe two in the back. And in one of

the rooms was a motorbike, the driver sitting in the adjacent room, safe from the rain. A clothesline

full of laundry hung over the motorbike, and next to the bike, three blue plastic

chairs, where we were to sit. So we all crammed into this tiny, muddy, dusty

room: Agnes, me, the motorbike, the clothes, and nine children. Justine, the

mother, shuffled in, and nodded to us quietly. The children were smiling, as we

all laughed over the rain drenching us. Without room to maneuver, we

surrendered the food, and Justine slowly smiled. The children excitedly

took their lollipops; the ice was broken. We sat down on the chairs. Agnes tried

to help me keep my briefcase from resting on the floor, but we had no choice;

and my briefcase is made for rugged travel.

sponsorship program, why we were here and how we could help. Now we had to do

our interviews. Nine children: Rose, Florence, Isaac, Daniel, Simon, Annette,

and three with hemophilia—Kato, Vincent and Lawrence.

|

| Justine is only 30 but must care for nine children, three with hemophilia, on $1.50 a month |

Justine shares her family information with us:

her husband Peter is a lumberjack but must travel far with his employer to

where they can cut trees. He is not home much. He can be gone for up to 30 days

at a time, leaving her with the nine children and hemophilic bleeds to deal

with. And with that, there wasn’t much else to say. I noted the look on her

face: distant, furtive, stressed. She looked to be about 45, and I was stunned

when Agnes said softly, no. She is only 30.

which is good. The school is less than a mile away, and sometimes Justine must carry the children on her back when they have

bleeds. She tells us she fears for the children with hemophilia at school. “Caning”—corporal

punishment—is popular here and causes the children to have bleeds.

While she speaks, a weak and wet kitten hobbles

in, sores on its back, and sniffs at my feet. A scrawny chicken pokes his head

in the door then scuttles off. The children wait patiently for their turn to

speak. I feel something at the back of my neck; the oldest daughter, Rose, has leaned

over to touch my blond hair. Then she touches my forearm. They want to feel my

hair and skin, which feels and looks different from their own. I smile and give

her unspoken permission by my playful response, trying to “catch” her in the

act by grabbing her hand. She smiles back.

water, no plumbing, no electricity. They use candles at night. No place to keep

food. How does she feed nine children? I ask about meat: do they get beef,

chicken? Agnes just looked at me oddly. “Meat is Christmas,” she said. “It’s

too expensive; they may have it once a year.”

|

| Kato |

|

| Vincent |

|

| Lawrence |

hemophilia, had a twin brother who died at nine months from a suspected bleed. Kato is a

gem. He is responsive, curious, engaging, and always ready to smile. His two brothers are more studious

and quiet, and very shy. Interviewing them was difficult. But Kato couldn’t

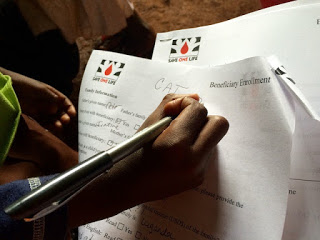

wait to show us what he knew. He can write a bit in English! On the Save One Life new beneficiary form, he carefully wrote “Cow.” This was a

revelation. Together with his winning personality, there is surely hope for him

someday to rise above his origins.

|

| Kato watches Agnes intensely |

|

| Kato can write in English! |

While

Kato peers intensely into Agnes’s face as she is speaking to Justine, I glance about the home. No light can get in except through the splintered front door,

which is narrow. There are windows but they are boarded up with cloth and

cardboard. Malaria and yellow fever are rampant here, and so this must be some

attempt to protect them. The rain drums the steel roof, making it

hard to follow the conversation and translation.

pinpoint the same problem we have seen with the other families: they live too

far away for immediate treatment. It takes literally hours of rough travel to

get to Kampala for treatment. They can’t afford the transportation costs: motorbike

up to a main road, then public transport. And picture yourself on a 100-250cc motorbike

on these bumpy dirt roads with a bleed, then another two hours on a public bus

crammed with people. It’s pure torture.

|

| They love new York! |

The biggest shock of all was when we asked

Justine for her monthly income. $1.50. Surely we heard wrong and we ask again.

No, $1.50. She wants a little money so she can set up a small vegetable stand

and sell whatever vegetables she has left over. Or maybe participate in a craft

to sell goods. She wants to be more independent because she can’t rely on her

husband’s income.

|

| Laurie Kelley and Agnes with Ssempa family, Uganda |

When we finish the interview, the rain waned, and the sun was shining. Within minutes, the ground was drying, the water

receding, and we stepped outside for photos. Again I take out my New York City Chapter

t-shirts, the cleanest things around here, and the three hemophilic boys put

them on proudly. We have to leave, and promise to help. Even with the children smiling,

Justine cannot muster a smile. Her eyes gaze to somewhere else and she seems

without hope. Only little Kato carries the energy and dreams of the family. I

feel he is the one who will truly benefit from our attentions, so that he can

one day care for his mother as a man.

As we return to our world, Kato’s smile would cheer me, and Justine’s face would haunt me for days to come.